My body remembers Korea.

My fingers, cheeks and toes remember the bitter bone deep chill of Korean winters. Frostbite from a winter training exercise is my constant reminder of my time in the snow capped mountains. I am now forever sensitive to the damp and the cold, meaning I am also forever sensitive to the land of Korea.

Personal photo from an observation deck overlooking the demilitarized zone (DMZ) into North Korea. Taken by me sometime in late 2013.

More importantly, I am forever sensitive to the people of Korea. Both North and South. The remainder of this post is me speaking from that sensitivity.

I spent two years living in Seoul, knowingly in the direct impact area of every weapon in the North Korean arsenal. I was there as an American soldier, specifically a military intelligence professional. I worked with South Korean police, regularly conscripted soldiers, and Special Forces soldiers.

Me, terrified next to a South Korean border guard at the DMZ circa 2013. Picture taken in the United Nations negotiation room, where North and South Korean officials meet.

For a year I debriefed North Korean defectors, citizens who fled the hermit kingdom (at risk of sentencing their entire families to political concentration camps) for a chance to live in the “freer” Korea.

A North Korean border guard observing us from across the street at the “demilitarized” zone.

(unfortunate FYI: North Koreans that fled to South Korea can never fully assimilate into their brother country. Despite being ethnically identical, the imposed cultural borders between North and South Korea are too strongly fortified.)

….. literally across the street.

Maybe it’s because my body remembers that I’m currently so incensed.

Seminar was honestly appalling for me this week.

Maybe it’s because I’m still quite personally attached to the welfare of Koreans so I foolishly expect other people to feel as I do. Maybe it’s because I didn’t fully realize how little most Americans know about a land that our country has been actively terrorizing for the past 60 or so years. Maybe it’s because I felt most of my classmates engaged with the text as if there weren’t real people attached to the deeply painful and horrific narrative we read. As if the people we’re reading about were just tragic caricatures. Or worse, as if the people of both Koreas are not currently in fear of their lives every day because this country hasn’t stopped violently meddling with them since ~1948.

Maybe it’s because I spent two years in a “strategic” position, whose official strategy was that if South Koreans die, American soldiers will die with them in a show of solidarity. So every time this country played with Korean lives from 2012-2014, my life was being gambled with too.

Maybe it’s because I realize that I wore a uniform of oppression while telling the people I oppressed that we’re friends. Even as they let me know that the jeopardy of their lives was the direct result of a destructive system that i was perpetuating. (The only reason there are two Koreas is because of America’s proxy war with the then USSR.)

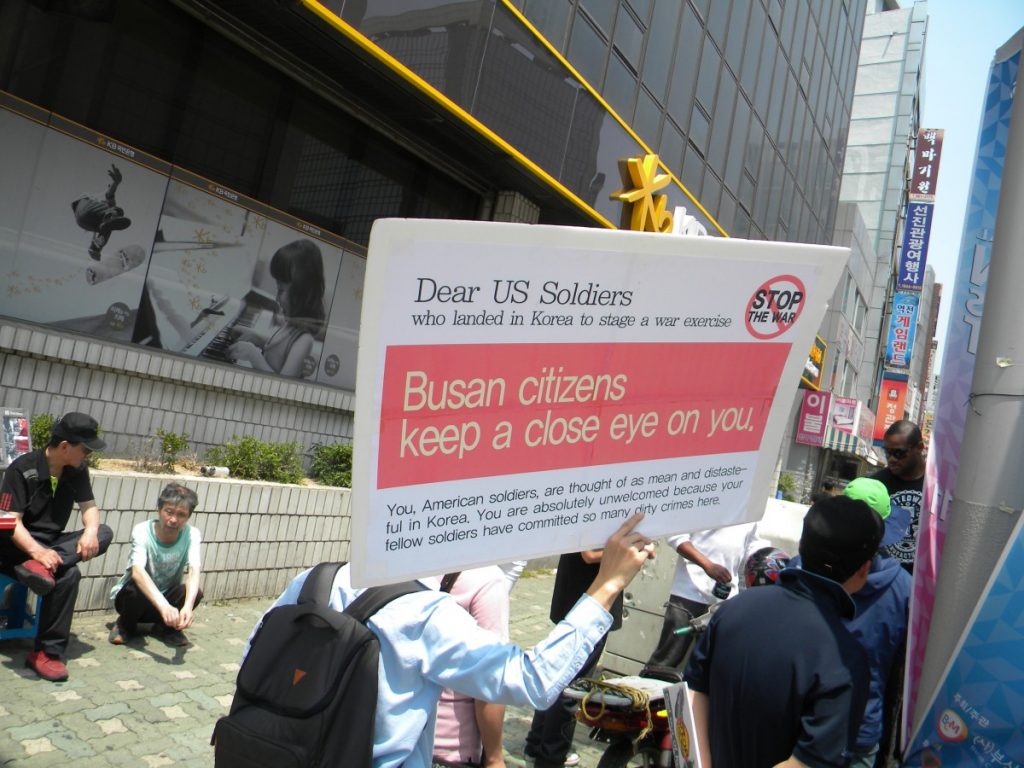

image from citizens in Busan fervently protesting the arrival of US sailors for a war exercise. taken by me in 2013.

Maybe I’m upset because as I read Forgotten Country, every page resonated with me.

I identified with the intergenerational conflict.

The constant silencing of major family traumas.

The casual encouragement that non-white and especially non-masculine people are given to make ourselves smaller and easier to consume.

I felt the bloody and lasting impact of seemingly endless war.

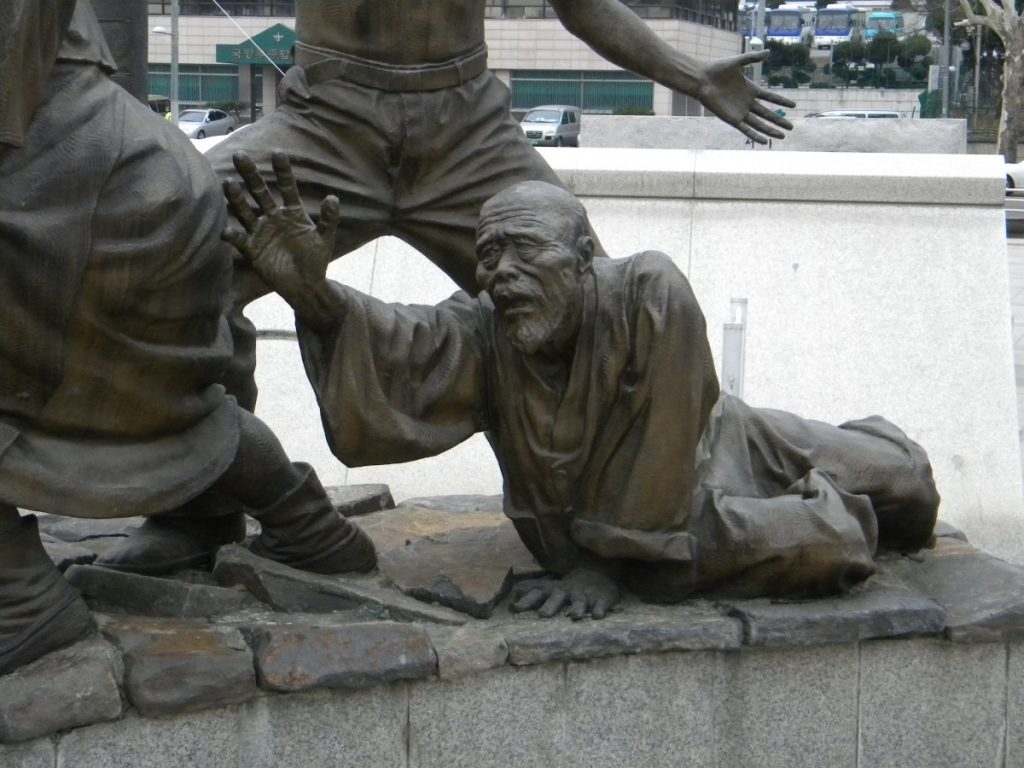

Part of a statue from the Korean War Memorial Museum in Seoul.

I felt the cheapness of individual lives in the grand scheme of the western war machine.

I felt the refusal of bystanders to bear witness to atrocity and hold space for healing.

I feel the weight of the merciless massacres of resistors.

And I will never adjust to the constant rewriting of history, in which we’re painted as the good guys.

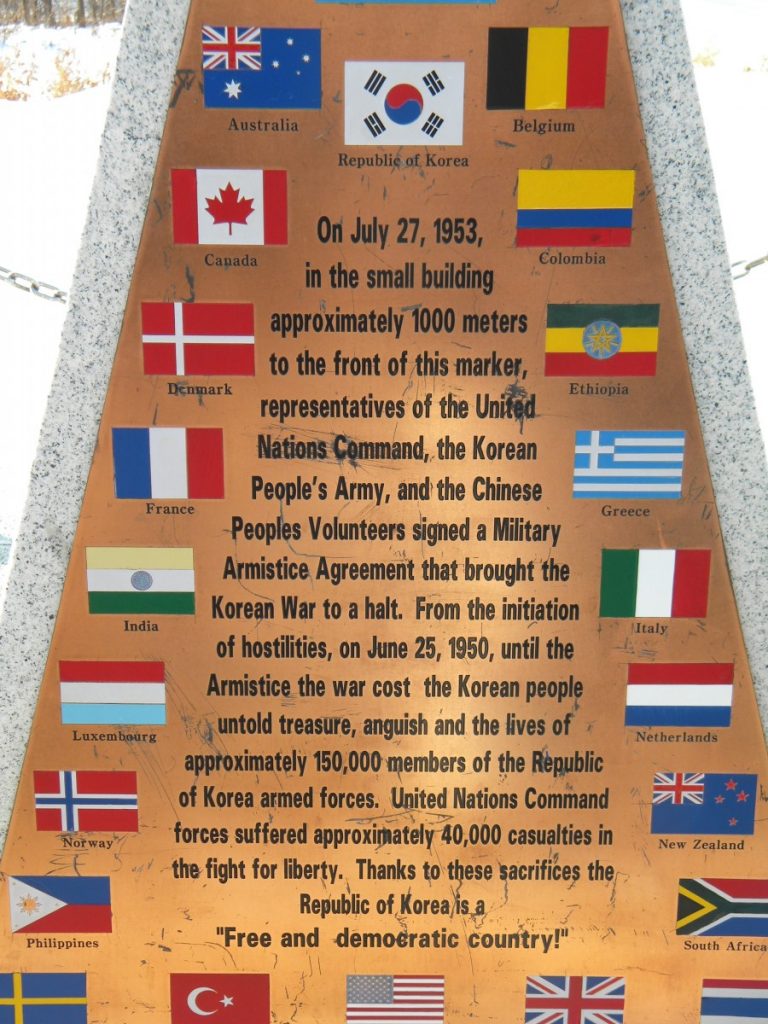

“free and democratic” and forcibly occupied.

Because it’s disgusting.

Honestly, America is disgusting.

As a person who sacrificed years of my life in its service, I need to scream to anyone who’ll listen that this country rests on a moral base of slow-churning filth. This country has since its very inception. And as a nation, we forcibly export our filth to the rest of the world, then turn around and call our filth good, righteous, correct, ideal. We train people in our filthy ways to perpetuate our filthy cycle.

America is coated in so much blood that we can’t keep it to ourselves. So we spread our blood worldwide and leave it to mix into the soil of the indigenous people of wherever we decide to occupy.

And then we, the people, forget about it all.

We hang up some yellow ribbons and miniature flags — because we claim to support our inherently murderous troops — and then we forget them at our earliest convenience. And we forget the names and locations of the countries we invade. We forget why they were invaded; we forget which lying justifications we were sold to casually kill so many families with our tax money.

We forget that the targets of our bombs are families.

We forget that the people of “enemy” countries are actual people.

Or maybe we never learned that. Maybe we were never supposed to learn that.

Maybe that’s what we are presently here to learn.

Anyway.

One of the most striking parts of Chung’s narrative in Forgotten Country was the absence of directly implicating America(ns) in the

torturous tale of the family’s disjointed lives. And while I’m loving this class so far, I wish we had more time to unpack the histories of these countries of origin. This week made me realize that history is such a central part of API-American stories. Outsiders can literally never understand where folks are coming from without knowing their history.

Losing history is like losing our collective memory. As a nation, we can certainly function with memory loss, but as Chung repeatedly

illustrated, our body does not forget its experiences.

All of these suppressed memories will make themselves (painfully) relevant again.

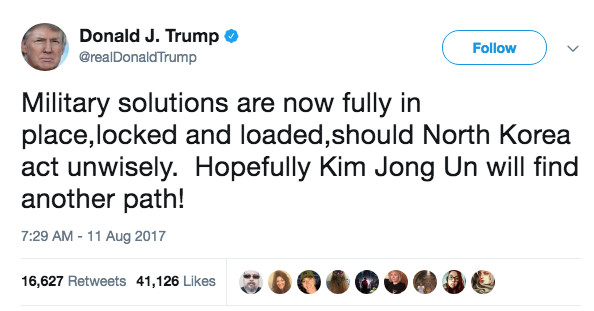

screenshot from this Vox article.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.