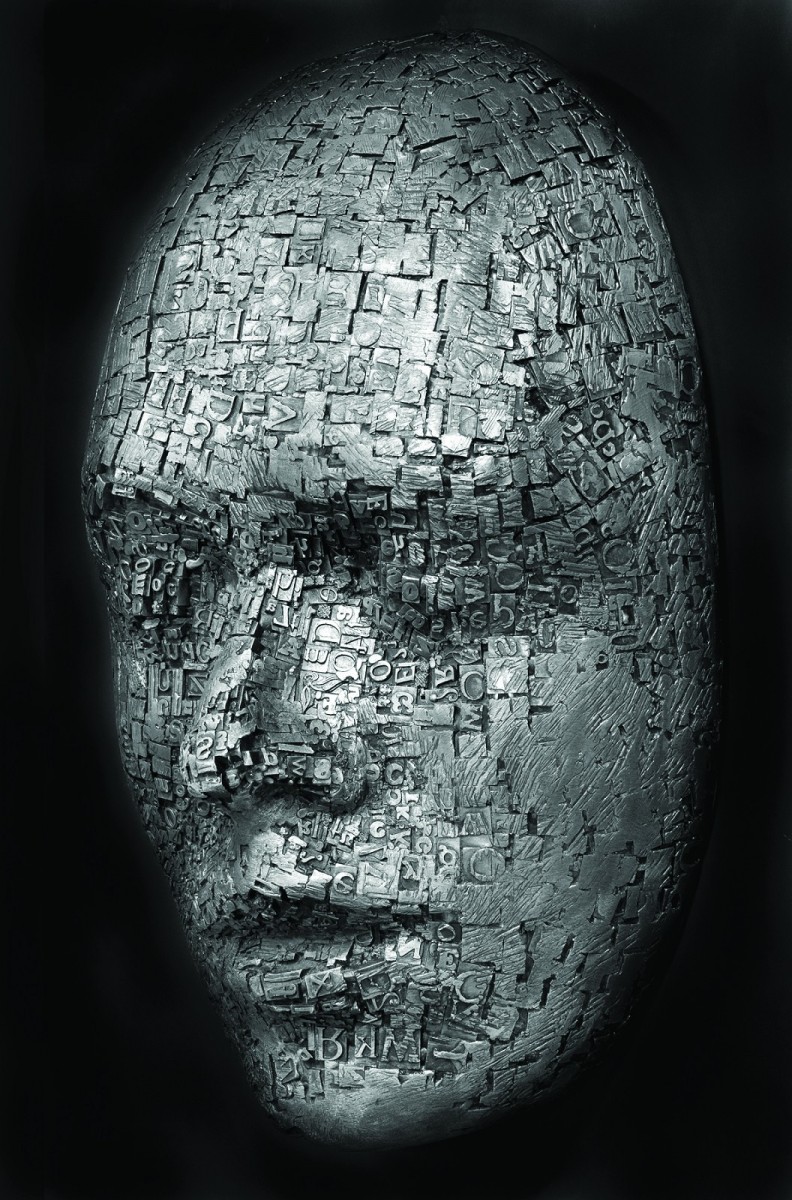

Photo of a sculpture by Dale Dunning Retrieved from http://oenogallery.com/assets/Artists/dale-dunning/palimpsest-17-1.jpg

He opened his eyes and was struck.

-St. Augustine’s Confession

It is spring and the oppressive grey of the woods surrounding my home has given way to a vibrant and dizzying green. I have only lived in this place for six months and the majority of that time has been spent under the dark skies that define a Pacific Northwest winter. Now the Sun pulls me from the womb of my room and I spend hours walking the feral and overgrown streets of my neighborhood. Everything feels transformed, reborn through the magical process of photosynthesis.

These walks are meditative but it is not the quiet meditation of the sitting monk. My brain is so overloaded with the sensory information that tells the story of this place, that I have no space left to think of anything else. My boots scuff the gravel at the roadside causing the pleasant sound of locomotion. I carry a small pink Moleskine notebook and Pilot pen in my pocket so that I can remember that which is worth remembering.

***

Language is a wild and living thing. Speaking gives breath to thought; writing makes thought concrete. Thinking and writing are both sensual pastimes. We take information in through our bodies, we smell, taste, touch hear and see, and from this information we construct a narrative which in turn leads to the construction of a life. Thinking can exist without writing but writing should never exist without thought. When we write we hold in our hand a tool made of wood and graphite or fossil fuels and carbon. With these tools we litter pages made from the pulped remains of dead trees with the symbols of language recognized by the culture to which we belong. In essence, this is not so different from the animals painted on cave walls all around the world by our way back ancestors. Writing is a place where reality and dreams can merge, where the conscious mind is allowed to dance with the subconscious mind. Mythos and logos all rolled up in one tight bundle of deerskin and dried flowers.

***

The air is so thick with the scent of blossoming plant life that I can taste them, as if I am smelling with my tongue. I list the names of the plants that I am acquainted with: self-heal, Indian plum, stinging nettle, salmonberry, licorice fern, salal. All these plants are native to this place, this is where they belong.

I listen as unknown birds call from tree to tree and try to imagine the conversation that is taking place. I wonder what information they are sharing with one another. The chickadee is calling out its own name, chick-a-dee-dee and then chick-a-dee-dee-dee-dee, each extra dee a sign of increasing danger. I hear the telltale buzzing of hummingbird wings. I do not actually see the tiny bird as it whizzes by but just the same, I know it is there. As I take notes on these birds, I notice a small insect crawling across my left hand, too light to be felt. It pauses a moment, leaps from my hand and is gone.

***

In her essay Learning the Grammar of Animacy, Robin Kimmerer writes, “But to become native to this place,if we are to survive here and our neighbors too, our work is to learn to speak the grammar of animacy, so that we might truly be at home.” To be at home in a place, wherever that may be, is to acknowledge that you are an animal existing in this place and that the thinking you do is shaped by the sensual stimuli provided by that place. Later in her essay, Kimmerer discusses the ways in which Native American languages address what we in the West think of as inanimate objects, with verbs rather than nouns. What does it mean “to be a bay”, “to be a hill”, to be a tree or to be a bird? For that matter, what does it mean to be a human?

When we separate the act of being from the act of thinking, we are further separating ourselves from the living world around us. When a person is deep in thought, is it not possible that the wind blowing through their hair might influence their thinking or the blazing red of the setting sun might add a new dimension to a thought?

If writing cannot be separated from thinking, what would it mean if we considered our surroundings while we were writing? What if we allowed setting to constantly influence our thinking? Perhaps it already does and we simply do not take the time to notice. Surely as I sit here in the library, typing these words on my computer, my thinking is different than what I write while walking outside. Surely the fluorescent light influences my mind differently than the light of the sun. In the library there is a certain sterile sort of silence, punctuated with the occasional sniffle and cough. Outside I hear the singing of birds and the buzzing of insects. As David Abrams writes in his book Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, “Such reciprocity is the very structure of perception. We experience the sensuous world only by rendering ourselves vulnerable to that world. Sensory perception is this ongoing interweavement: the terrain enters into us only to the extent that we allow ourselves to be taken up within that terrain.”

It is this sensual way of thinking that allows a poet like John Haines to write the way he has written in his poem Horns.

I went to the edge of the wood

in the color of evening,

and rubbed with a piece of horn

against a tree,

believing the great, dark moose

would come, his eyes

on fire with the moon.

I fell asleep in an old white tent.

The October moon rose,

and down a wide, frozen stream

the moose came roaring,

hoarse with rage and desire.

I awoke and stood in the cold

as he slowly circled the camp.

His horns exploded in the brush

with dry trees cracking

and falling; his nostrils flared

as swollen-necked, smelling

of challenge, he stalked by me.

I called him back, and he came

and stood in the shadow

not far away, and gently rubbed

his horns against the icy willows.

I heard him breathing softly.

Then with a faint sight of warning

soundlessly he walked away.

I stood there in the moonlight,

and the darkness and silence

surged back, flowing around me,

full of a wild enchantment,

as though a god had spoken.

***

Further up the road my presence is noted by the barking of yard dogs. In one yard two huge Great Pyrenees leap at the fence. On the other side of the road a rottweiler and pitbull join the chaotic chorus. I turn a corner and a yellow labrador also seems offended by my existence. He is chained up next to a four wheeler that is parked below an American flag. The flag is snapping in the same breeze that is causing the trees to rustle and sway. A yellow sign nailed to a tree reads, “Drive carefully. Our squirrels can’t tell one nut from another.” Across the street two mallards burst from unseen water in a ditch, startling me.

The calling of the birds increases as the light fades and the evening gives way to the night. I turn and head towards home. The bullfrogs have begun to chirp, welcoming the darkness. They are joined by an echoing and repetitive ping which is followed by a pop. I turn to look, my eyes seeking out the source of the sound. I see the black silhouette of a man splitting wood in the deepening night.

Leave a Reply