The Science of Taste

Neurogastronomy and Organic Gardening

Category: Project Weekly

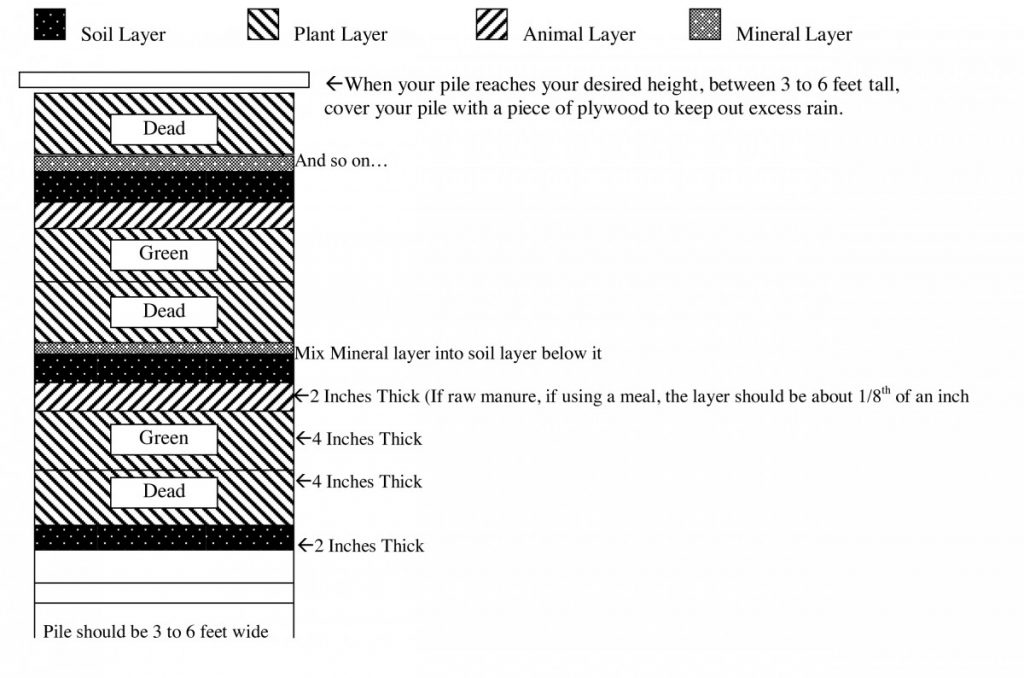

I learned the SPAM method with Gail at Fertile Ground, layering Soil, Plant, Animal, and Manure to build a rich compost. This method comes from the Black Lake Organic Nursery in Olympia.

“The making of quality, humanized humus requires reaching a certain stage of decomposition through “cooking” diverse ingredients in a “biological fire.” This “fire” is generated by feverishly working and rapidly reproducing microorganisms under optimal temperature, moisture, aeration, nutrient and fuel (food) conditions. A minimal pile size (one cubic yard, or 3 ft by 3 ft by 3 ft) is needed to insulate the succession of working organisms and allow heat build-up to about 130 to 160 degrees. A temperature of 140 degrees Fahrenheit is optimal. This heat build-up cannot occur in sheet composting, low piles, or poorly constructed piles using a low diversity of materials such as leaves or all grass clippings. The best initial composition will include animal manures or animal by-products and rapid construction of a complete pile over a period of a few days or less.”

We worked together as she explained the composting system to sustain the weeding that I was doing in the sidewalk garden lots. She talked about the general principle behind the three bins, one for green, one for woody, and one for the layering. During that process she explained to me that we need more green which breaks down quicker (the nitrogen) to add to the woody brown dead stuff (carbon), to build the layers with a green and brown ratio, adding chicken manure, and then watering the compost to create a rich hummus like what you find on the forest floor.

This information was so helpful to understand the dynamics of the layers, to build heat and break down the organic matter into hummus. At Red Dog Farm the composting was on such a grand scale, it was hard to interpret how it really worked. Gail reminded me that however balanced we want the ratio of carbon and nitrogen to be, we have to go with the flow of the seasons and compost what is available. On Red Dog Farm, time spent on the clock prioritizes action and we let nature break it down for maximum production. I am applying this layering method to our small scale gardening project in Port Townsend. Improvements are needed to break down the soil faster, utilizing the black plastic compost tumbler into the rotation.

Hands on work reinforced knowledge I obtained at Fertile Ground. Gail’s instructional teaching of principles allowed me to reinforce my own understanding of the principles and create a successful, organized system of composting.

Last week’s sound experiment of sourdough flatbread with arugula, basil, lemon, and olive oil spread was a failure and I couldn’t help but wonder why it wasn’t as successful as the yogurt experiment.

Neuroenology: How the Brain Creates the Taste of Wine .

© 2015 Shepherd; licensee BioMed Central. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which stated that,

“The multiple neural mechanisms involved in producing flavor include sensory, motor, cognitive, emotional, language, pre- and post-ingestive, hormonal, and metabolic. It can be claimed that more brain systems are engaged in producing flavor perceptions than in any other human behavior.”

To successfully engage in the multisensory experience of intentional eating I needed to utilize as many senses as possible.

“Flavor is a multi-modal sensation. It is multisensory, involving all the sensory systems of the head and upper body.” (Shepherd 2015)

Of the five senses, my pesto engaged a strong visual reaction – which is key.

Closer visual inspection strongly influences the expected flavor (“We eat first with our eyes”) (Shepherd 2015)

The fresh pesto color was bright green like guacamole or the first green shoots of spring – a good first impression in the experience of eating this meal.

TOUCH- a creamy textured paste

SOUND- In addition to the crunching sound sensation, I added brass music enlisted to support the bitter taste.

“The multisensory perception of flavor” (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00321) and “As bitter as a trombone: Synesthetic correspondences in non synesthetes between tastes/flavors and musical notes” (doi:10.3758/APP.72.7.1994)

TASTE-pungent (fresh arugula), sour (sourdough), bitter (walnuts), lemon, garlic and the crunch of crispy sourdough, yet what was missing was the SMELL, which seems to be the predominate sense involved with the fabrication of flavor.

“So most of what we experience as flavor is odor or aroma.”

McGee, H. (2004). On food and cooking: The science and lore of the kitchen. New York: Scribner.

If I prepared this dish again, I would increase the aroma of the pesto by adding more garlic or an herb with stronger aroma, maybe thyme, rosemary, sage, mint or even nutmeg. (McGee 2004)

David Shepard states that, “Cooking would obviously have also enhanced the flavors of the food.”

Although, when I tried cooking the pesto into the sourdough, it lost its color, its zing and flavor.

“Flavor therefore has the quality of an illusion. This makes flavor vulnerable to many influences, as is well recognized by food producers in formulating and promoting their foods. Food producers spend millions on research to use the sensory illusions to influence our choices of food, in our homes as well as in the supermarket and the school cafeteria.” (Shepherd 2015)

“Flavor therefore has the quality of an illusion. This makes flavor vulnerable to many influences, as is well recognized by food producers in formulating and promoting their foods. Food producers spend millions on research to use the sensory illusions to influence our choices of food, in our homes as well as in the supermarket and the school cafeteria.” (Shepherd 2015)

The creation of illusion as found is the basis for the commodification of food through the spice industry and artificial chemical flavorings – which is another whole topic on its own.

Week 7 was spent applying information learned from “The multisensory perception of flavor” (https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00321) and “As bitter as a trombone: Synesthetic correspondences in non synesthetes between tastes/flavors and musical notes” (doi:10.3758/APP.72.7.1994) a tasting lab in Week 8.

When looking at figure 3 in the synesthetic correspondences in non synesthetes article, I saw that there was a higher approval rate amongst the tasters for the piano sound throughout the five groups in the pleasantness rating graph relative to the approval rating of the brass in the intensity and the complexity graphs, and a relatively neutral response for the strings and woodwinds.

“Brass was often matched to unpleasant stimuli, whereas the piano was preferred for pleasant tastes/flavors” (Cristinel & Spence)

The table 1 chart shows that vanilla and sucrose had an extraordinarily high concentration relative to the incredibly low concentration of the citric acid and caffeine. Figure 2 shows that out of a maximum count of 68 (34 participants doing two tests) at least 10 more people matched piano to sucrose and brass instruments to caffeine than the correlation with the pairing of strings and woodwind instruments to coffee. The appreciation of sucrose and caffeine may be related to what type of memories are paired with those flavor associations.

“The main point is that, whereas the representation of smells in the olfactory bulb is driven by stimulus properties, the representation in the olfactory cortex is memory based.” (Shepherd: 103)

“In the west, we describe the aromas of strawberry, caramel, and vanilla as smelling “sweet” (Stevenson and Boakes, 2004).” (Spence 2015)

When looking at the chart on page 392 and 393 of On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen I noticed cinnamon had a description for the fresh, pine, citrus, floral, woody, warm, and penetrating flavor components, but not distinctive. Other spices with descriptions for several penetrating flavor components had distinctive smells to them. I remembered from last quarter Meghan mentioning how effective cinnamon can be used as a sweet substitute. In the synesthetic correspondences in non-synesthetes article, figure 2 shows an even count from the participants when identifying woodwinds and strings with vanilla.

“For example, the odors of vanilla, caramel, strawberry, and mint induce sweetness enhancement in western countries where people often experience those odors with sucrose.” (Auvrey & Spence 1018)

Supplies: small grater, plain yogurt, cinnamon sticks, bowl, vanilla extract, fuji apple, speakers and song by Ryan Zak – New Life

The experiment facilitator cut the fuji apple into a few slices, applied a few drops of vanilla extract into a bowl with plain yogurt. The participant was asked to close their eyes before the song was played and to mix the yogurt with an apple slice when the sound of cinnamon grinding stopped and to taste. Shortly after the participant finished chewing the apple, the facilitator asked an unexpecting participant what the yogurt tasted like.

The experiment provoked a strong mouthfeel reaction. The music had a soothing effect and the scent of the cinnamon provided an incredibly permeating feeling. The participant focused on the apple’s texture during chewing and when asked the question of what flavor came up, the participant described the powerful mouthfeel reaction rather than the taste of the apple and vanilla-cinnamon yogurt. The participant described a prior intention to enjoy the textural properties of the apple slice which could have contributed to an inability to describe the taste.

“For example, Frank, Van der Klaauw, and Schifferstein (1993) have shown that sweetness enhancement of a sucrose solution that can be elicited by adding strawberry odor only occurs when the participants are asked to rate sweetness and nothing else; however, when they are also asked to judge other qualities, such as sweetness, saltiness, sourness, and bitterness, the sweetness enhancement effect disappears.” (Auvrey & Spence 1020)

Anoth er food lab was practiced to better understand the effect of brass music while tasting on bitter flavors. An arugula, basil, lemon, and olive oil spread was mixed on sourdough flatbread. The results for this sampling were inconclusive because I was not treating it with the same intention (partially because it was my dinner) and while I was excited from the previous success of the last meal, there was no synesthetic response and the feelings were rather anticlimactic. The texture of the flatbread stood out and the bitter and sour flavors of the spread held no connection to the song (EPL cover of My Girl).

er food lab was practiced to better understand the effect of brass music while tasting on bitter flavors. An arugula, basil, lemon, and olive oil spread was mixed on sourdough flatbread. The results for this sampling were inconclusive because I was not treating it with the same intention (partially because it was my dinner) and while I was excited from the previous success of the last meal, there was no synesthetic response and the feelings were rather anticlimactic. The texture of the flatbread stood out and the bitter and sour flavors of the spread held no connection to the song (EPL cover of My Girl).

This week I explored the neural interconnectivity of shared general-domain functions of the brain and how it can be used to enhance an experience with food. At first I was unable to find cited articles on music and food, so I explored the research on language and food. The following quote comes from an article providing evidence for shared general-domain functions of the brain and the usefulness of neural connections in application.

“If long-term experience with music only sharpened shared acoustic processing abilities in language, then this would indicate that a domain-general processing mechanism account would suffice. However, in order for a theoretical account to be complete, transfer effects should be taken into consideration. If long-term experience in one domain not only sharpens common characteristics but also domain-specific characteristics, this would indicate that experience can transfer from one domain to the other.” (Asaridou & McQueen 2013)

The knowledge that experience can transfer from one domain to another does not mean that it can be applied, as described by the following quote:

“They [Bidelman et al. 2011b] found that tone language experience enhances subcortical pitch processing in a manner similar to musical experience. However, this was not evident at a behavioral level. Although Mandarin speakers performed better than non-musicians, the FFR (Frequency Following Response) response accuracy was a successful predictor of behavioral performance only for the musician group. Thus, while subcortical pitch encoding is sharpened in tone language speakers, this is a necessary but not sufficient condition for perceptual advantages to occur in behavior.”

Tonal language speakers have an increased behavioral advantage to differentiate between tones, timbre, and texture in conversation with more than one person while the musician group’s Frequency Following Response was more accurate as a predictor of behavioral performance (potentially due to varying subject content across all communication through spoken language).

The limitations of the neuroplastic development amongst musicians relative to Japanese and Dutch speakers in the context of differentiating between language lead to concluding thoughts as described in the following list of quotes.

“In a cross-linguistic experiment with Japanese and Dutch speakers, Sadakata and Sekiyama (2011) showed that although discrimination and identification of non-native temporal and spectral speech contrasts was better in musicians, there were stimuli for which musicianship had no advantageous effect.”

“It is therefore not automatically assumed that a domain-general sound processing device is more resourceful, and this can only be manifested when new learning is required.”

“The fact that musicians are better in segmental processing of a non-native language is an example of transfer as defined in this framework.”

Interestingly enough the neural connections made by differentiating between tone, timbre, and texture do in fact overlap if the two functions are reinforced by the principle that underpins both behavioral functions that activate a shared general-domain.

In examining studies on tone-deaf, tone-based language speakers, the authors stated: “Interestingly, neuroplasticity in pitch processing at this subcortical level of sound encoding is not restricted to the domain in which pitch contours are relevant. Strong effects of context which arise in other studies do not seem to influence brainstem responses. This finding led Krishnan et al. to conclude that language and music are “epiphenomenal” with respect to subcortical pitch encoding and that the encoding mechanism has evolved to capture information in the acoustic signal that is of relevant in each domain, in order to facilitate higher-order cortical processing of pitch across domains.” (Arasidou & McQueen 2013)

The language in the last sentence of this quote interests me because the capturing of acoustic signal that is relevant to each domain in order to facilitate higher-order cortical processing of pitch across all domains, which includes eating because as I learned pitch is interconnected with the perception of smell, further reinforcing the vibration theory of olfaction rather than the shape theory of olfaction.

The following article I found summarizes the literature on the multisensory perception of flavor and cited other research to show that flavor is not defined as a separate sensory modality but as a perceptual modality that is unified by the act of eating.

“… according to the amodal approach, perceptions are not based on sensations but rather result from a process of information extraction. The information is abstract and does not depend on the particular sensory modality in which it was generated. Properties of objects can thus be ‘interpreted’ by different sensory channels. As a consequence, sensations are specific to each sensory modality, but perceptions are not (e.g., Gibson, 1966, 1979; O’Regan & Noe, 2001; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991)” (Auvrey & Spence 1025)

The authors referenced the use of ecological theories of perception to define flavor as a perceptual modality which was incredibly exciting to hear because it should support the vibration theory of olfaction. After reading Shepherd’s Neurogastronomy I learned that the olfactory system is used in part to detect danger, pheromones, and food. After discovering concentric circles last week it was brilliant to hear that the ecological theory of perception supports the potential for an increased understanding of the interconnectivity of smell and hearing. The following quote lead to an increased understanding of the potential connection between the otolith organ and this articles understanding of olfaction constituting a dual modality.

“Olfaction thus appears to constitute a ‘dual modality’ in that it explores objects both in the external world and within the body.” (Auvrey & Spence 1022)

The parts of the otolith organ helps coordinate gravity, balance, movement, and directional indicators which interests me because of the interaction between this organ’s proprioceptors and the vestibular system in the brain creating exteroception, a perception of the outside world, versus interoception, how one perceives pain, hunger, or another emotion. The similarities between how the ear operates and the apparent constitution of dual modality by olfaction is reinforced by the following quote.

“In addition, the fact that the same unfamiliar odor can induce different taste qualities (i.e., sweet or sour) as a function of its repeated pairing with a specific tastant shows that the modification of taste qualities by odors is not due to a particular feature of the odor but is a consequence of learning instead (Stevenson & Tomiczek, 2007).” (Auvrey & Spence 1018)

Going back to a previously listed quote on the article on evidence for shared general-domain functions:

“The fact that musicians are better in segmental processing of a non-native language is an example of transfer as defined in this framework.”

Varying taste qualities depend on behavioral experience and learning that result in matching an unfamiliar odor to, in this example, sweet or sour. As mentioned in the quote listed before the quote on musicians, the repeated pairing with a specific tastant shows the modification of taste qualities as a consequence of learning. Musicians are commonly used in studies of neuroplasticity in the human brain, and when examining the malleability of the interpretation of a sour taste and sweet test, it tends to make more sense to think about minor and major chords (sour and sweet) given the key (tastants) of the song (chemical releases of the food itself) and the style in which it is played, or how it is perceived (previous flavor experiences).

The following quote describes the interdisciplinary neurological connections that go into the flavor of a meal.

“The multiplicity of interactions between taste, smell, touch, and the trigeminal system (not to mention hearing and vision) has led numerous researchers to propose flavor as the term for the combinations of these systems, unified by the act of eating (e.g., Abdi, 200; McBurney, 1986, Prescott, 1999; Small & Prescott, 2005).” (Auvrey & Spence 1026)

The unification of taste, smell, touch, and the trigeminal system has lead me to focusing on the unmentionable hearing and visual side of flavor. As mentioned in the first quote listed from this article, “perceptions are not based on sensations but rather result from a process of information extraction”. This quote reminded me of the difference between retronasal smell, smelling from the mouth to the nose when eating, and orthonasal smell which is smelling something that exists in the world. The following quote further supports the theory of shared general-domain function.

“Thus, smelling and tasting need not be defined by receptors and nerves; they can instead be defined by their functions in use. As a consequence, the same olfactory receptors can be incorporated into two different perceptual systems, one for sniffing and the other for eating. Smelling would be restrained to its main function, that is, the detection of stimuli at a distance by means of their odors.” (Auvrey & Spence 1022)

The quotes mention of “the detection of stimuli at a distance by means of their odors” reinforces my initial belief of the connection between the vibration theory of olfaction and hearing frequencies. The two different perceptual systems of smell in addition to olfaction detection of danger, pheromones, and food and the connectivity between the brain’s vestibular system leads me to believe that the use of concentric circles was developed through nomadic campfire encounters in which language barriers were crossed, danger was heightened either from human to human interaction or a fear of a new environment, a high likelihood of increased pheromone release, and of course, food.

Music can alter the perception of a flavor (Kantono et al). This week I have tried to figure out why, and I have started to ask how it can be explored on a personal level. For a week 8 project, I am going to prepare a meal for others in the class, I thought it could be fun to experiment with kinesthetic combinations of flavor and music to conclude my study of Shepherd’s Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters. Before doing so I had to understand which theory of smelling suited my understanding of the text: the shape theory of smell via the lock and key mechanism or the vibration theory of olfaction via inelastic electron tunneling.

“The taste nerves enter the brainstem, the part of the brain that is directly continuous with the spinal cord and that is responsible for automatic functions such as control of heart rate, breathing, and other vital activities.”

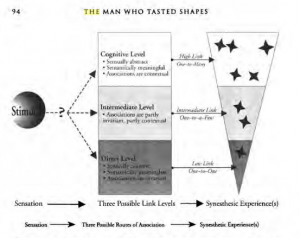

“Reasoning through the gustofacial reflex, I concluded that the mechanism of synesthesia and its link would have to be above the level of the brainstem. (It would presumably not be at this level given that synesthetic responses were idiosyncratic rather than identical as in the gustofacial reflex.) Similarly, evidence gathered so far about language indicated that synesthesia would probably not occur at this highest level of abstract brain processing. The link had to be somewhere in between.” (Cytowic 93)

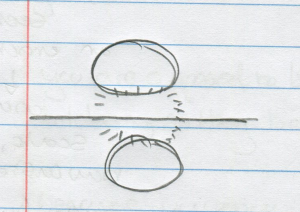

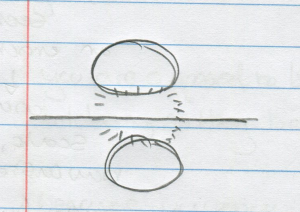

The following image is from Cytowic’s The Man Who Tasted Shapes. I noticed some similarities in my drawings from the first section of my response to Shepherd’s Neurograstronomy and this depiction.

The line represents the stimulus that can be interpreted at a direct emotional level, the circle below, which might resemble Kahneman and Tversky’s “fast” emotional responsive side of the brain, and the circle above which represents a higher cognitive level of interaction that could represent the brain’s “slow” mode of rational thinking. The intermediate level I discussed in my previous post was only in terms of culture and how it can remove from the ability to be, but here I realize that balancing the interaction between the direct level of interpretation and cognitive levels of interpretation can be attributed to culture, personal ability to develop the emotional capacity of direct levels of understanding, personal ability to develop a sharp mental capacity to understand the interaction between how you want to exist and what emotions are driving your existence – and my favorite – the personal ability to trick yourself into believing you understand any of it.

“An interesting idea. It is the sensation that is memorable, not the name. The name is just semantic baggage attached to it.” (Cytowic 94)

“Luria’s patient S shows this very clearly,” I said. “Despite his prodigious memory, he sometimes made mistakes.Those mistakes were not in reproducing what he was asked to remember incorrectly but in omitting some items from large series. He would use the method of loci, an old memory trick, by placing his synesthetic images throughout an imaginary town and when reading them off as he mentally strolled through it. When he did omit items, his explanation was not that he “forgot” but that he didn’t see them as he walked through his imaginary town.” (Cytowic 94)

This is where I have begun to think about the falsehoods of smell as a lock and key puzzle described with visuals.

“What I am saying is that cross-modal associations are the foundation of language. According to the standard view, language is the highest type of cross-modal association and especially depends on the highest type of cross-modal association and especially depends on the tertiary association cortex and linkages between one part of the cortex and another.” (Cytowic 95)

“What has drawn even more attention to this topic is the fact that extensive music training enhances auditory processing not only within but also beyond this domain, to general and auditory and speech processing. This finding is of great value to our understanding of auditory perception mechanisms and their plastic properties. In particular, it indicates that at least some auditory mechanisms are domain-general in nature, and thus are not special to either music or speech processing. (Asaridou & McQueen)

In my effort to better understand how music and food are interconnected I had to decide which theory of smell best suited my understanding of flavor.

The vibrational theory of olfaction originated in 1928 by Malcolm Dyson and was expanded on by Robert H. Wright in 1954 after it was abandoned in favor of the competing shape theory. Luca Turin revived this theory in 1996 that proposed a different perspective of the mechanism described by Linda Buck and Richard Axel describing the use of the G-protein-coupled receptors in the context of molecular locks and molecular keys to describe unlocking scents. This perspective asked if molecular vibrations using inelastic electron tunneling could be happening (Wikipedia).

In an article from Scientific American, Mark Anderson mentions that odorant molecules usually have hydrogen atoms. In the makeup of these atoms, each very chemically similar to each other, there are different isotopes that strongly affect how a molecule vibrates. A hydrogen nucleus with both a proton and a neutron could be used to better understand the vibration theory because human noses can sniff out the presence of a least some kinds of deuterium (double sized hydrogen with a proton and neutron, rather than just a proton).

“Olfaction is trying to be like an analytical chemist,” Turin says. “It’s trying to identify unknowns.” Chemists identify unknowns using spectrometers. The article mentions how Turin published controversial findings in Nature Neuroscience, and he responded to a negative finding of his experiment in 2004, and explained that it may generate a weak vibrational signal that humans cannot detect. Eric Block, professor of chemistry at the University of Albany, states that Turin can’t have it both ways: they either smell deuterium or they can’t (Anderson 2017).

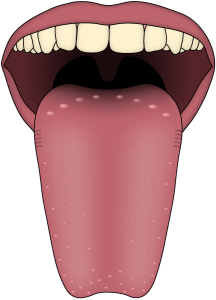

After hearing about how smell plays a vital part in creating flavor, I wonder if humans can smell deuterium and they can’t because of how it is recorded into memory. This image shows in a very simple way how the process of smelling comes from various signals in the mouth, through my hand sketched-on depiction of the olfactory receptor cells leading into the olfactory bulb, and into the brainstem.

I can’t honestly explain how we perceive smell with anatomy, it confuses the life out of me, but the important takeaway from the diagram is that the tongue, mouth, and all the glands apart of the tasting process send signals to the brainstem while the olfactory receptor cells and olfactory bulb interpret the smell by creating an odor image.

On page 99 of Shepherd’s book on neurogastronomy he asks, “Why is it that the coordinated, multidimensional smell image from the olfactory bulb cannot be sent straight to the highest cortical level – the neocortex – to serve as the basis of perception?… It [the olfactory cortex] represents the transition to the steps of creating the perceptual qualities of smell. It is where the external features of the outside world meet the internal features of our perceptual world.”

A quote from Shepherd on page 119, “There is thus a sharp contrast with the olfactory nerves that enter the front of the brain closest to the highest cognitive centers. It is as if the multisensory flavor sensation is designed to allow ingested foods to be analyzed at both the highest cognitive level as well as at the level of the most vital functions. It has all bets covered.”

So again, can humans smell deuterium and can they not based on how they form the perception of the food and how that perception coexists with the ability to store the odor image as memory?

Shepherd writes about a scientist Haberly who suggested in 1985 that the “olfactory cortex serves as a content-addressable memory for association of odor stimuli with memory traces of previous odor stimuli. He noted the properties necessary for the cortex to function in this manner: a large number of integrative units (pyramidal neurons and synapses) relative to the number of memory traces; a highly distributed, converging-diverging, input (from the olfactory bulb fibers); and positive feedback (the re-excitatory axon collaterals) via highly distributed interconnections between units… Not surprisingly, this basic microcircuit is similar to that in the hippocampus, which is well known for its role in long-term memory. The final property necessary for a cortex to mediate learning and memory consists of the synapses that are reinforced by coincidental action or presynaptic and postsynaptic activity. This is the so-called Hebb rule, named after the psychologist Donald Hebb, who in 1949 suggested that his coincident action would build memory into brain circuits. This too is a property of the synapsis in both olfactory and hippocampal cortices” (Shepherd 101).

The following page describes how the olfactory cortex matches inputs to memory. “The main point is that, whereas the representation of smells in the olfactory bulb is driven by stimulus properties, the representation in the olfactory cortex is memory based.”

Shepherd writes, “This system learns. The basic cortical circuit has the ability to improve its performance with repeated exposure to different smells. The recurrent excitation strengthens the cells activated by input from the olfactory bulb. The lateral inhibition enhances the contrast between activated and less activated cells. Finally, the synaptic strengths change so that the system can store these changes as a memory and match them to the input.”

Shepherd also writes, “The olfactory cortex responds especially to changes in its input signals from the olfactory bulb; it adapts (reduces its responses) to continued stimulation with the same smells.”

This leads me to believe that lateral inhibition was intended as a defense mechanism for humans to smell changes in its environment as a means of detection, which becomes stored as a memory and attached to the input of the smell.

Finally Shepherd states, “These changes with learning enable the system to improve its ability to match an input pattern to a stored pattern, so that finer discrimination between more similar smell molecules can occur. These changes also enable the system to improve its signal-to-noise ratio, so that detection and discrimination of a particular smell can be enhanced against a background of many smells.” (Shepherd 103)

In an article by Tom Brown Jr. on Concentric Rings in nature published in The Tracker magazine in 1984 describes the navigation of stimulation responses when hunting in the woods. Tom Brown Jr. recommends “learning to establish the symphony”, and in the context of the article, is the process of tracking animals in the woods in circular motions as to not create another concentric ring that interferes with the one you are pursuing. For practice, he advises trying to read the concentric circles that are sent off of a particular friend entering the woods after you have sat and established a symphony for a while (Brown 1984).

I don’t think the tracker is able to sit down and triangulate the shape of the animal’s movement through the woods better than the tracker is able to use his nose as a tuning fork, striking a deep breath of fresh air to pick up on resonating frequencies nearby. Over time the tracker’s ability to detect concentric rings increases because of how smell is stored into our memory. The recurrent excitation of smelling with every breath, plus the lateral inhibition of similar smells becoming dulled over time, lead to quicker responses in recognizing changes in the smell environment.

This week I feel like I had a breakthrough with my independent studies as I met with Gail at Fertile Ground and discussed my direction moving forward with my internship.

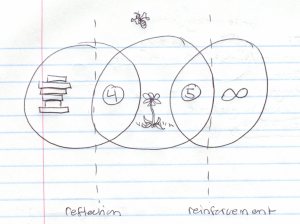

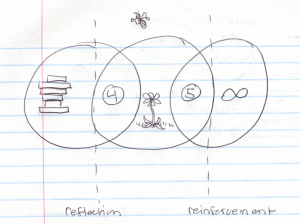

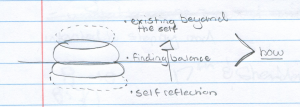

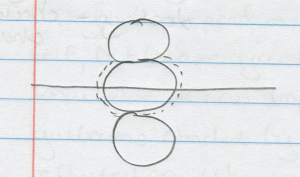

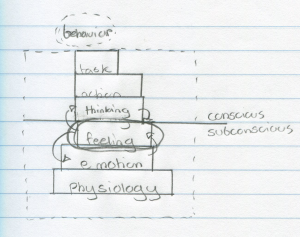

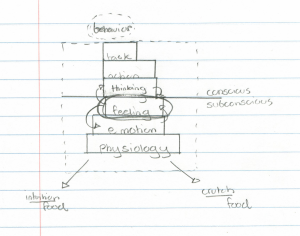

This image shows a new organization of the depictions I have been creating for the last few quarters to show how to be. Last week I was hoping to organize some ideas that were inspired from Shepherd’s book on neurogastronomy. The dotted lines running through the stacked boxes and the number 4 and the number 5 separated from the infinity symbol attempt to show the tunnel vision of focus on a desired way of being. The flower in the middle shows the potential growth and how your being might create a buzz is shown above the middle circle.

Let’s begin with the stacked boxes on the left.

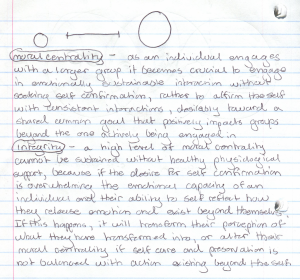

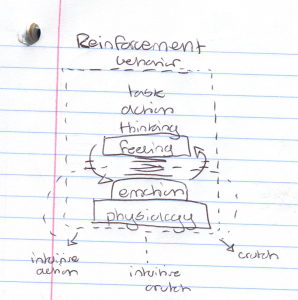

As described in the week two post, this depiction created by Dr. Alan Watkins shows how we physiologically sustain thinking and our actions to accomplish a desired task which is reflected in our behavior. How we go about sustaining our physiology depends on how we sustain our emotions .

beyond ourselves. This picture above represents the 4 in the original image. The following picture describes the pitfalls of an extended moral centrality and reliance upon a group for reinforcement of behavior, rather than using the ability to reflect in what that behavior actually does for others amongst that shared group. When a person reflections upon their actions amongst a group after being with them, not as a form of reinforcement, it contributes to that person’s sense of being and allows for a person to expand on how their behavior exists beyond themselves. Not until the past few days have I realized how rewarding cooking with other people can be when the recipes hold complexity that would not be enjoyable to attempt individually. The ability to exist beyond the sense of self in effort to sustain other’s physiological self and providing emotional support for the words unspoken by sharing a space has become internalized as powerful mode of social resilience.

Now that we have looked at how physiology, moral centrality, and integrity exist in our way of being it is importance to look at how that may change over time.

This image represents the the number 5 in the space between the circle with the infinity loop and the growth that leads to our being. The difference between the first physiology image and this one is that there are lines to represent whatever added bullshit we have that prevents us from truly being happy and existing in a sustainable joyous way that benefits others beyond our immediate selves. This section describes the fear in our human attempt to bend backwards to correct for a cultural malformation that has impacted us all in varying ways, and our different perceptions of how it has affected us can be celebrated in sharing the enjoyment of sustaining positive emotion as described in 4 through cooking, music, theater, or any form of creative expression that nourishes the emotion of performers and viewers. Emotion exists in our subconscious as a representation of the physiological signals that are getting sent to the brain that can only be processed through feeling. If I have created an intuitive crutch, for example a set of jokes that turn an unprocessed aspect of my life into immediate comedic relief, I am able to trick myself that that quirk could not use some attention to live a happy, more complete life

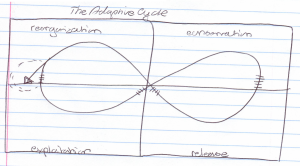

This lopsided depiction of The Adaptive Cycle that describes human and environmental interaction over time is a helpful tool to show how the use of the intuitive crutch can trick the mind.

There is a quote from Michel Foucault’s The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical perception that describes the deceit of the rational thinking of the human brain, “Death left its old tragic heaven and became the lyrical core of man: his invisible truth, his visible secret.”

After reading the assigned portion of The Lives of Animals did I uncover the rational mode of thinking is synonymous to my idea of the intuitive crutch. It can be used to process emotion through creativity, but relies upon the logic of a shared environment and not until a new perception of the immediate environment is created can other environment’s logic be used to sustain a healthier, more conscious way of thinking.

As described in my notes between winter and spring quarter, with no idea of the context,

“The intuitive crutch can be unknowingly used by tactful or incidental decreased conscious awareness of behavior in effort to seek acknowledgement for suffering, which means increased conscious awareness and connection with the intuitive self is essential, how?”

If the conscious self can learn and develop behaviors to preserve the emotional integrity of the intuitive self through controlling for the wildcard rational way of thinking, then being is revealed to the conscious self as incredibly simple, and eventually it won’t need constant reflection. The box on the far left represents how we can sustain our physiology in an emotionally sustainable way that rewards ourselves and connects us with others through forms such as cooking, music, and theater while the infinity symbol on the right shows how intentional breathing and meditation can lead to more integrated forms of self preservation through qi gong breathing and integral consciousness training. Distress can be composted, grown, and harvested to sustain the farmer through dance – a celebration – of peaceful relations between the mind and body set the tune of music, rhythm, and release – and when the sense of self is developed, it can be tested, and challenged through tactful invitations of perceived danger through any meaningful way to the individual, for me, I have noticed there’s some beauty in the traditions of martial arts and chess.

Last week I was stumped by the concepts of contrast enhancement and lateral inhibition in space and time as described in Gordon Shepherd’s Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why It Matters.

“He [Hartline] further showed the mechanism that produces them [Mach bands]: lateral inhibitory connections between the receptor cells. Through these connections, the strongly excited cells at the border more strongly inhibit the weakly stimulated cells, and the weakly stimulated cells more weakly inhibit the strongly excited cells. The mechanism is called lateral inhibition. The effect is called contrast enhancement, because the difference between the light and dark areas is enhanced at their boundary. In a general sense, contrast enhancement also is a kind of feature extraction, the enhanced response to specific spatial features in a visual scene. This is contrast enhancement in space.” (Shepherd: 61)

“Hartline’s laboratory also showed that there is contrast enhancement in time. When there is an abrupt increase in illumination, a single cell responds with a large increase in impulse firing, which rapidly declines to a steady level somewhat higher than before. The overshoot in impulse frequency is called the phasic response, in contrast to the steady tonic response. It shows that the nervous system is sensitive primarily to a change in the environment rather than to an unchanging steady input. This contrast enhancement in time is the counterpart to contrast enhancement in space. After the initial increase in stimulation, lateral as well as self-inhibition comes to counterbalance the higher level of steady stimulation.” (Shepherd: 61/62)

I hope to eventually be able to explain human behavior in the context of lateral inhibition and contrast enhancement in space, and why it is a kind of feature extraction. Until I get there, these are my thoughts.

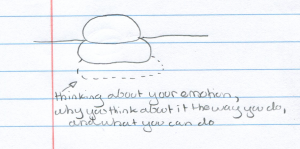

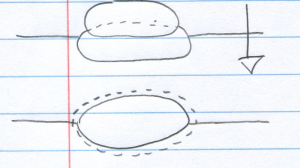

I have not started reading my assigned text Thinking, Fast and Slow and I hope to revise this understanding as the quarter progresses. These two beautiful blobs represent two modes of thinking, often understood as higher consciousness and lower consciousness. I believe the “lower consciousness” is actually your brains “fast” emotional mode of thinking and the “higher consciousness” is the brains “slow” intellectual mode of thinking, designed to reflect on the emotional mode of thinking’s sentience. Lateral inhibition describes the checks and balances system of the brain, as Shepherd states, the mechanism, and the effect is called contrast enhancement, which I think can only be thought about as moving through time.

The effect of contrast enhancement can be understood in the terms of emotional consumption. If something wants to shine more brightly than others, it could consume the emotion of its surroundings to create a sharper contrast of itself amongst everything else, or it could try and shine brightly and positively affect everyone’s mood by a powerful individual presence. How that happens can be understood in two different ways.

The first way is to self reflect.

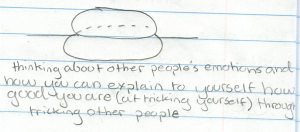

The second way is to seek an understanding through others.

The first way to reflect is inspired by an event that jolts the person into a phasic response through an overshoot in impulse frequency in contrast to a steady tonic response which might be described by the second way of seeking an understanding. After the initial increase in stimulation, lateral as well as self-inhibition (could be described by using lenticular logic) comes to counterbalance the higher levels of steady stimulation.

So let’s look at the effect of contrast enhancement in both approaches, starting with self reflection.

In the emotional reaction following the phasic response, a person can self reflect and find balance through understanding both methods do not exist in absolute indifference (look at a yin-yang symbol, to a small degree one exists within the other). How one finds a balance through their understanding of lateral and self-inhibition will affect how they exist beyond themselves.

In the second emotional response, a person can seek an understanding through others rather than self reflection. Over time, an understanding will be found and the principle behind their actions will exist in some way beyond themselves as interpreted by the people they affected. As that person continues to deflect accountability, the use of lenticular logic persists as shown in the diagram above to defend their sense of being formed through this emotional response following the phasic response. Think about a part of Shepherd’s quote in the context of preserving the natural environment,

The overshoot in impulse frequency is called the phasic response, in contrast to the steady tonic response. It shows that the nervous system is sensitive primarily to a change in the environment rather than to an unchanging steady input.”

and what the health of the environment might represent to someone altering their perception of how they exist in the context of their environment.

Earlier in the week I began understanding contrast enhancement in the context of humans through internalizing that humans are supposed to be emotionally blinded by their children to offer the opportunity for change and understanding of what the previous generation has done in order to adapt to their understanding of the environment as the next generation comes of age The blinding process is supposed to encourage an increased understanding of the “higher consciousness” brain’s mode of thinking. But are human’s nervous systems doped on electronics getting encouraged? Or having a phasic response? Contrast enhancement in time exists for all organisms, that’s what natural selection is. Natural selection amongst humans is a mythical origin story that has formed from the fallacy of thought that humans are often believed to be superior, or greater than nature, which was not apparent until we completely destroyed that sense of self through the natural environment. Natural selection amongst all species is very real, but how that species separates itself through contrast enhancement determines whether or not that species will die off or evolve in its ability to co-exist with other organisms.

If the importance of self-preservation is internalized after the phasic response with a similar amount of emotional intensity, you can end up developing a wonderful system to preserve the self, but because you know the importance of the concept so well you might find security in your knowledge or approachof understanding of how to preserve the self which could be blinding if you are in a state of emotional need and seeking affirmation. If this occurs your perception will be altered because you may have become emotionally invested in that knowledge itself rather than applying that knowledge to your brain’s emotional way of thinking because of how you formed a sense of identity through your culture through the use of an intuitive crutch (an immature phasic response reinforced over time).

This picture represents an undeveloped sense of self formed in an oppressive culture seeking affirmation between both modes of thinking in the brain. How this unidentified self finds balance again affects how it exists beyond itself. Seemingly, why can’t a good intentioned person apply their understanding to themselves if previously internalized ideologies stand in the way of the ability to honestly reflect on who they are? If the culture that you formed your sense of identity in and other members consumed by that culture attacked you because you represented what it was denying and couldn’t understand it, and you couldn’t understand why you were being attacked and loved simultaneously, then over time many will feel they don’t deserve to feel happiness if they persist through it. How we understand the phrases attacked and loved depend on the person’s understanding of their experience and the context of how their experience shaped their perception. That is why the use of the intuitive crutch itself persists so heavily today.

This week I also thought about the concept of genius. As previously stated, the “slow” mode of thinking in the brain is an inhibitor to the “fast” mode of thinking, and the balance in between can be described as the line that is present in all of the hand drawn diagrams. This happens in moments until the genius concept is applied to preserving the body’s physical and emotional state to sustain that level of thinking. If this is done repeatedly across time, you can rewire your brain to manufacture something in the physical realm that simulates existence beyond the perceived world as exemplified by John C. Lilly’s use of hallucinogenic drugs and his creation of the sensory deprivation tank. The intellectual capacity of utilizing both modes of thinking was exemplified by the mind of Einstein and his capacity to use both modes of thinking simultaneously. If you think too emotionally and develop through the “fast” systematic mode of thinking that includes the rational mode of thinking, you can end up rewiring the emotional attached side of your brain to be your own version of higher consciousness – an intuitive crutch. This can be used with good or bad intention because as you seek to sustain emotion, whatever state it may be, you develop or sustain emotional crutches on a personal and large scale. This is how caste systems are manufactured – manifest destiny through consistent tonic responses.

This week I also thought about what this means in the context of experiencing “the other”:

People that leave their sense of self to experience “the other” with the intention to return back to their sense of self are doing so by “thinking fast” and bring their systematically developed modes of thought with them, which may or may not have already been developed and wired into the brain over time to incorporate the comfort of what they are leaving to enjoy the experience of leaving their sense of self even more, while seeking for confirmation of how good (they are) their ability to convince themselves through other people is. If they seek out the other in the most honest way, without reflecting on how their intense phasic response is transmitted their culturally assisted sense of self, (as shown in the image below)

they are only reinforcing their belief that they have left themselves and become what they dreamt they could be, but over time only dream up ways to reinforce the belief in the false sense of self. Social media reinforces this falsehood that we need to represent well and be this magnificent image in other’s eyes. As this continues to happen, a person might know that what they’re doing isn’t correct, but the emotional immaturity to get rid of their “progress” allows for someone to pity their growth which affects how they continue to satisfy a state of need through developing a prosthetic heart (negative human innovation to confirm one’s sense of brilliance).

Meditation and Rice

How much you fill your rice cooker with rice is an act based on your hunger. The reflection of your state of hunger can be understood by how much water you decide to add to it. Too much water, and you have watery rice, and you don’t deserve that do you? We all are more than willing to self-pity over watery rice, but it is easier to stir the rice and continue to wait patiently. When filling the bowl of rice with water it is wise to note if you are scared of burning the rice. If there is a lot of water in the bowl, maybe decide to stir the bowl more than once before you decide the rice is cooked. If impatience overcomes the meditation and watery rice is eaten without accepting why the rice might be watery, it might be reflected in how much spice was applied to the rice. If the rice is cooked with patience, I bet your spices will provide a near perfect season to your meal.

Finding your spice

I love thyme. Why? It smells good. How you go about tasting thyme determines how much the smell of thyme can transfer to your sense of taste – if you focus too much on how good thyme smells it might affect how you concentrate on the scent itself, which can affect the quality of the desire to taste the smell of thyme. When I desire thyme too much, I end up flavor blasting my rice and all I taste is thyme. I have to remember, how strongly my impulse to concentrate on the scent itself can affect the quality of the desire to taste the smell. You might think you want all of your rice to taste like thyme, but thyme only reflects the rice itself, and sometimes that can taste a way that doesn’t line up with our own perception of our spice.

Week 2

The hundred pages I covered this week in Gordon M. Shepherd’s book was comically informative. I took four quotes from the text to outline my mode of thinking throughout the first two sections of the book. The first quote,

“The reason for this [olfactory pathway probably being the most heavily modified pathway in the brain] appears to be that our perception of food smells is heavily dependent on our behavioral state: whether we are hungry or full, angry or sad, craving for something or repulsed by it, suspicious of a new food or eager for novelty. The smell image has to be modified by the behavioral state.” (Shepherd 2014: 98)

follows Shepherd’s description of the constant modification of the olfactory pathway relative to other modified pathways in the brain.  This quote instantly reminded me of Dr. Alan Watkin’s presentation of how to sustain a high level of thinking through the depiction of how our physiology affects our thinking. This depiction shows how our physiology sends various electromagnetic signals from our body’s organs to our brain (understood by scientists as emotion, or energy in motion) and how that is consciously understood by us as thinking about how we feel. Emotion is interconnected with feeling just like feeling is interconnected with thinking. The capacity of our body to perform an action towards a desired task is reflected in our behavior. Our behavior can be described as a symptom of our human condition.

This quote instantly reminded me of Dr. Alan Watkin’s presentation of how to sustain a high level of thinking through the depiction of how our physiology affects our thinking. This depiction shows how our physiology sends various electromagnetic signals from our body’s organs to our brain (understood by scientists as emotion, or energy in motion) and how that is consciously understood by us as thinking about how we feel. Emotion is interconnected with feeling just like feeling is interconnected with thinking. The capacity of our body to perform an action towards a desired task is reflected in our behavior. Our behavior can be described as a symptom of our human condition.

The following depiction of Dr. Alan Watkin’s presentation includes my input of intuitively processing emotion and satisfying the “need” to process emotion with a crutch. Food can help alleviate a need to process emotion by reducing physiological stress. “Food” such as chemically engineered flavor packets or other chemically induced fast foods can also be used as a direct means to satisfy a temporary need by providing immediate stimulus at the cost of a food hangover of sorts. If the smell image has to be modified by behavior, which exists as a symptom of human functionality, shouldn’t the emphasis on eating be placed on why not what?

emotion by reducing physiological stress. “Food” such as chemically engineered flavor packets or other chemically induced fast foods can also be used as a direct means to satisfy a temporary need by providing immediate stimulus at the cost of a food hangover of sorts. If the smell image has to be modified by behavior, which exists as a symptom of human functionality, shouldn’t the emphasis on eating be placed on why not what?

The second quote,

“In the same way, [comparing smell and color] we postulate that our smell world would also be only a smear of shades of inchoate sensations set up in our noses if we did not have the circuits in our smell pathway that select specific types of molecule stimulated activity to give them a quality we can identify as distinct from all the rest.” (Shepherd 2014: 87)

describes how the brain perceives molecular stimulated activity in our smell pathway by creating a quality to identify a distinction between other smells. Relating this to the first quote, if a person’s environment supports their behavior and does not support or provide an emphasis on the importance of distinguishing quality to identify certain behaviors as distinct from the rest, then the smell world is but a smear of shades of inchoate sensations. The nose knows.

In the next quote Shepherd describes the exact physiological processes that enable the system to improve its ability to understand input patterns to allow for an increased ability to discriminate between more similar smell molecules.

“This system [interactions between the olfactory cortex and olfactory bulb] learns. The basic cortical circuit has the ability to improve its performance with repeated exposure to different smells. The recurrent excitation strengthens the cells activated by input from the olfactory bulb. The lateral inhibition enhances the contrast between activated and less activated cells. Finally, the synaptic strengths change so that the system can store these changes as a memory and match them to the input. These changes with learning enable the system to improve its ability to match an input pattern to a stored pattern, so that finer discrimination between more similar smell molecules can occur” (Shepherd 2014: 103)

The quote mentions the basic cortical circuit has the ability to improve its performance with repeated exposure to different smells. This increased perspective can help enable the system to improve its ability to match an input pattern to a stored pattern. If different smells are hidden from a young nose, and the young learning system is enabled to match an input pattern to an existing stored pattern this only allows for reinforcement of the same smells. If an individual’s environment promotes an emphasis on what to eat rather than how to eat then the olfactory pathway’s storing of the smell as a memory after the odor image is affected by behavior might be affected if the person’s perception of their behavior is not entirely honest. So let’s be honest, if your behavior stinks would you want to smell it?

“The olfactory cortex microcircuit functions to take an input reflecting many diverse stimuli and construct out of it a coherent odor object. This is an analogy with how the visual system takes an input of different shapes and sizes and constructs a “visual image”. An important aspect of such an object is that seeing only a small part of it still enables the system to “fill in” the missing parts.” (Shepherd 2014: 103)

The ability in the olfactory cortex microcircuit to recognize patterns allows for the system to complete an incomplete image even if only a small part of the incomplete image is available. If our perception of food smells are heavily dependent on our behavioral state, and there is a strong sense of need to satisfy emotion, couldn’t that influence how we seek to satisfy our need to eat food? Over time couldn’t that influence how we learn to smell? Over time couldn’t that influence how we learn to “fill in” the missing parts? If it becomes a part of our behavior, wouldn’t it be easier to change the perception of the behavior itself?

Food creates culture.

Flavor is our perception.

Quit tasting.

Smell.

© 2026 The Science of Taste

The Evergreen State College

Olympia, Washington