Final Presentation

Making Cheese

I love cheese. I love thinking about it, I love eating it, I love going to the grocery store to buy cheese, or better yet to a farmer’s market. I love bringing cheese to parties and making a personal cheese board after a long day. Thus, after being a longtime fan of this food I’ve often dreamt about learning how to make it, which has been a part of human’s cuisine for thousands of years. Now I am fulfilling this dream by learning how to make cheese in one of the countries that is most famous for its cheeses! Dreams do come true, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Claudio Cavazzoni makes cheese once a week, every Wednesday, except for the third week of the month when splits the work between Wednesday and Friday. This is because every third Sunday of the month he attends the Fierucola market in Florence. The process takes about seven hours to make the magical transformation from a liquid to a solid, and seven different types of solid I might add. The milk must be warmed to begin, and because this is the EU and not the US the milk is unpasteurized, this is unadulterated, raw milk. It just needs to be a warm enough temperature so that the cultures added will be able to grow rapidly, ferment, and add a variety of flavors to the cheese. Claudio separates the milk into a few containers to differentiate the types of cheese that is to be made, and sets aside one small (ish) vat for yogurt. Each type of cheese gets a different species of bacteria because each species produces a distinct flavor, and over the years Claudio has found which species he prefers for each type of cheese, though don’t ask him for their names because he doesn’t know. He’s been doing this for 30 years, give him a break people! When he first started he was doing a sort of natural fermentation, that is using the bacteria that exists in the environment on the farm, but doing this makes for less consistent cheese, and if you’re trying to run a business naturally fermented cheese can be risky. Customers get used to expecting a certain flavor from you cheese as well as consistency in texture, and you have no way of knowing for sure what type of bacteria decided to make your cheese it’s home, so it’s much safer to buy the cultures and inoculate the milk.

The story goes that humans discovered how to make cheese by accident, thousands of years ago. When people were traveling from one place to another they would carry their water and milk in the stomachs of cows, and the rennet (an enzyme found in the stomach of mammals) would curdle their milk and when they ate it they realized how delicious it was, so they started making it intentionally. In today’s standards of cheese making the rennet is added after the cultures, the most important enzyme in rennet is chymosin, or rennin, because it gives the casein protein a sort of haircut by lysing the ends of the protein bundles (micelles), making these negatively charged proteins that usually repel one another come together to form a meshwork of proteins, which is what is happening when the milk begins to coagulate. It takes about 20 minutes for the milk to start forming a soft solid, and once it reaches this state it’s time to cut the curd to begin to extract the water molecules between the proteins. After the curd is cut it is then stirred to create even smaller curds and then scooped into plastic cheese baskets. There are a few different types of baskets used depending on the destiny of the cheese, for pecorino fresco the baskets have small holes to retain more water, while pecorino semistagionato and stagionato (semi aged and aged) have baskets with wider slits to more water to escape.

and when they ate it they realized how delicious it was, so they started making it intentionally. In today’s standards of cheese making the rennet is added after the cultures, the most important enzyme in rennet is chymosin, or rennin, because it gives the casein protein a sort of haircut by lysing the ends of the protein bundles (micelles), making these negatively charged proteins that usually repel one another come together to form a meshwork of proteins, which is what is happening when the milk begins to coagulate. It takes about 20 minutes for the milk to start forming a soft solid, and once it reaches this state it’s time to cut the curd to begin to extract the water molecules between the proteins. After the curd is cut it is then stirred to create even smaller curds and then scooped into plastic cheese baskets. There are a few different types of baskets used depending on the destiny of the cheese, for pecorino fresco the baskets have small holes to retain more water, while pecorino semistagionato and stagionato (semi aged and aged) have baskets with wider slits to more water to escape.

Once all of the curd is transferred from the vats to the baskets you let the cheese rest underneath a sheet of plastic that has steam hose in it on the stainless-steel table, which is at an angle to allow all of the water and the whey protein that leaves to cheeses to flow down into a hole that has a bucket placed underneath to catch all of this runoff. The whey runoff will be saved to make ricotta later, but we’ll get to that.

It only takes about 30 minutes for the cheese to begin to set in the basket, at this point you start turning the cheese and stacking the aged cheeses on top of each other to press more water and whey out of the curd. You turn the cheeses about four times, giving 20 minutes of rest between each turn. Once the cheese has gone through this process, so about 4 hours after being placed in the basket, it’s time to give those wheels a good salt rub. Each wheel is rubbed thoroughly with salt and is placed back into the basket to sit for another 12-24 hours depending on the size. I love this part because after you wash the salt off of your hands they are so soft. After all of this it’s time for lunch, so we eat a nice meal, have a bit of a siesta and then return to finish for the day.

Now it’s time to for ricotta to shine, all of the whey that was collected goes through about six or more filters between large vats using cheese cloth and a pump to make sure that there is no curd left. Once it has been sufficiently filtered the whey goes back into this giant vat that is then heated until the whey starts to coagulate. Once the coagulation occurs we take giant ladles and distribute them into the appropriate number of baskets. This ricotta is so good, I cannot explain how much I love the ricotta at Il Campriano. I will have dreams about it for the rest of my life.

Now back to the fresco and the stagionato cheeses, it’s time to wash those babies. Each wheel is given a rinse with water to get rid of the salt and is taken out of the basket and left on the table for one day. Pecorino fresco is place in a refrigerator after one day while the stagionato cheeses are transferred to clean wooden boards that are placed on top of the table for another day before being transferred to the cave. There they are aged for about 4 months (semi stagionato) to about one year or more (stagionato). The cave is essential for the aging process of chees, it can’t be too cold or too warm in order to have the perfect fermentation for flavor. The ideal temperature is about 52 degrees Fahrenheit (11 degrees Celsius), but can be between 60-37 (16-3). When the cheese is still very young it’s important to turn it every day, or every other day, otherwise it will stick to the board. After it’s had some time in the cave you turn them less frequently, maybe every three days. Once a month has passed they are transferred to plastic crates to make room for the new cheese, and there they are turned even less frequently.

The cheese making process really does feel like magic, of course it’s not magic, it’s microorganisms that are doing all of this work to make cheese so delicious and desirable by all. Even vegans attempt to recreate the wonders of cheese, but there has yet to be a substitute that even comes close to the real deal. I’m very fortunate to be in the minority of folks who have the lactase enzyme, and I’m not sure that I would be able to give up cheese if I didn’t, fortunately this thought is trivial and I will continue to eat my way through all varieties of cheese. This is beside the point. I probably could have dedicated my entire quarter to cheese making because there are so many things involved in this process. I barely talked about proteins, which I cannot express enough how much I love proteins, ask anyone that I know, I love polypeptides. Alas, I just wanted to give a brief run through of the process I’ve experienced during my stay at Il Campriano. If you’re interested in learning more about the science of making cheese I suggest reading On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee, it’s like a food science bible, one that I wish I brought on my trip, but I constantly refer to for any food related science inquiry.

Though my stay at Il Campriano has come to an end, I am so excited to bring this new-found passion and skill with me back to my life in the States, I’m planning on setting aside a few days each month to make my own cheese at home, and pecorino specifically. United States cheese eating citizens need to eat me pecorino, let’s make it a thing. Shout out to Black Sheep Creamery for going strong in Chehalis, WA. Until I can come back and tell the nation about the wonders of sheep cheese, I’ll just enjoy the pecorino that Claudio gave me as a parting gift from his farm.

Ciao ciao for now!

Il Campriano

I arrived at Il Campriano on April 30th, where I was greeted with a big smile by Maddelena Cavazzoni at the bus stop in Rosia, the closest village to her house that also has a bus stop. She drove me another 12 km to the final destination, the sheep farm that she and her husband, Claudio, own. Their farm is about a 30 minute drive from the city of Siena, surrounded by rolling hills and forests that open up into beautiful meadows with splashes of vibrant reds, yellows, and purples from wild flowers that paint the landscape. The location is very remote, with few neighbors, and even less cell phone reception. It’s incredibly dreamy, to say the least.

Claudio and Maddalena are originally from Milano, but a little over 30 years ago they were ready to leave city life behind and never look back so they settled in the hills outside of Siena and started making delicious pecorino (sheep cheese). The breed of sheep they raise is Sarda, which is an indigenous breed from the island of Sardinia. Claudio said if you go to Sardinia you would see these sheep all over the place, he chose this breed because of the high volume of milk they produce as well as the quality of the flavor of cheese made from the milk. In the earlier years of their pecorino operation, they had about 200 head of sheep, and he also grew his own hay, stray, and grain. Though, over the last three or so years they have slowly began to wind down and now the heard consists of 56. They have also stopped renewing their organic certification while still maintaining organic practices because the certification costs 800 euros annually (about $950), and due to the longevity of their business their customers know them and don’t need a leaf on the cheese package to trust that they are organic.

Cheese is made once a week, on Wednesday’s. He used to make it more than once a week, but now that the heard is much smaller it’s unnecessary because there is so much involved in the process of making cheese. Before, during, and after cheese making all requires a lot of tedious work, but I’ll get to that in an other post. He makes seven different types of cheeses: fresco, semistagionato, stagionato, Roquefort,ravaggiolo, ricotta, tomino, and eborinato, he also makes yogurt. On Thursday’s, Claudio brings some of his cheese to various shops in near by villages and to a few super markets. On Friday’s he sells his cheese at the market in Siena, which is where I am today. Finally, he attends the Fierucola market in Florence, which I wrote about in a prior blog post. It’s every third Sunday of the month, so I’ll be back at the market on May 20th, which is when I will end my stay at Il Campriano, but that is then and this is now. I still have nine days left with the Cavazzoni family and I’m so excited to get to make cheese for a third time, as well as take more walks through the woods, help with sheep maintenance, wash everything in the creamery many times, and if it doesn’t rain, next Sunday Maddalena and I will be going on a guided hike that her son and his girlfriend, Daniele and Irene respectively, will be leading that consists of walking along a river and stopping for yoga breaks.

In terms of food culture, the order of the food that is eaten and the way it is presented is consistent with family that I stayed with near Lucca. That is,meals start with the main dish, usually pasta or rice, followed by meat (if it’s on the menu), then a salad, other vegetables, bread is eaten between most of the courses to soak up any juices or oil left from the food, and then often times there is desert. This sequence of food is called antipasto, primo, contorno, and dolce. The food is not piled on one plate all at the same time, you eat each course separately (well not always, sometimes a salad and a frittata commingle, but the first course always gets the plate to itself), which allows the eater more time to meditate on each dish. I have noticed that the Cavazzoni’s eat more meat than the Martinelli’s, which Federico had mentioned would likely be the case in southern Tuscany. Of course they eat a lot more cheese than the Martinelli’s, Claudio pulls out a large box from the refrigerator that contains at least 4 types of pecorino for most meals, but not every meal because they don’t want their cholesterol to get too high, so says Maddalena.

Again, I have found such wonderfully hospitable hosts in Toscana. I see many similarities in the mentality of food and the Italian way of living (which I love), but it’s also a very different experience than my last. The farm is much more secluded and there are no children as opposed to the four lively Martinelli girls, and of course the vast difference between vegetable farming and cheese making. I love that I am able to spend time on two wildly different farms at two very different points in their life as a farm. I was a part of the fast paced life where the work never ended at Nico, and now I’m taking it slow as Il Campriano starts to wind down.

I’ll get into the magic of cheese making next time because it really does feel like magic.

Ciao ciao for now!

Reflection About Nico

I’m on a train heading to Siena, where I will spend the next three weeks on a sheep farm learning about animal husbandry and cheese making. I’m taking three trains, Lucca to Pisa, Pisa to Empoli, and Empoli to Siena, followed by a bus ride to the small town Rosia, outside of Siena, where my host family will pick me up. Basically, I have a lot of time to think about my time at Nico.

I went to Nico to learn about biodynamic farming, and like many people who have traveled and lived with families of different cultures than their own, I got so much more than I could have hoped. First, I want to address my current thoughts on biodynamic farming in comparison to my original ideas about this practice, but remember that all I really knew about it was the horn and the moon. Okay, sure it does seem a little voodoo esc, but Federico and his family seemed like any small organic farming operation that you would encounter in the states, but the Italian version. I asked him why he switched to biodynamic farming and he said that when you talk to conventional farmers and even organic farmers they’re always talking about all of the pests and weeds they have and how they are going to get rid of them. In biodynamics, farmers aren’t trying to mask the symptoms, they’re trying to cure the problem with incredibly healthy, living soil. It’s a very involved practice, Federico would work about 12 hours a day Monday-Saturday, and Sundays were spent around the house with his family and fixing the stone wall that collapsed from heavy rains. Biodynamic farming is certainly a lifestyle, one which you have to deeply love, but I think that’s true for all types of farming. My father and my uncles all had a very similar work schedule as conventional farmers. Farming is hard. I definitely do not agree with conventional practices, it was a quick fix to the rigorous rural farming lifestyle that has proven to be incredibly detrimental to the food system and the environment as a whole. Thus, I can see why people fall in love with biodynamic farming. It’s a holistic approach to farming, and if you’re interested in sustainable agriculture I highly advise you to look into biodynamic farming because it’s acutely in tune with nature, to the point of incorporating the cosmos in all of the work from seeding, transplanting, sowing, and weeding.

After reading Katherine Cole’s book Voodoo Vintner I was on the side that if you don’t make your own preparations, are you even really a biodynamic farmer? I totally agreed with this, until I talked to Federico. He doesn’t make any of his preparations other than 500, he gets them from a local woman who is a master at making them and tries to help her when he can. He brought up a point that Cole hadn’t considered, that is making the preparations is very difficult. If you don’t know exactly what you’re doing you could very well mess them up, so perhaps you should leave it to a professional, and if possible help them in the process. Additionally, he gets his finely ground quartz from another local biodynamic farmer, but he prepares the spray on site. I think this is a wise approach, not only are you sure that you are getting high quality preps, but you’re also building a strong community of biodynamic farmers in your area.

I also talked to Federico about how it seems like there are so many aspects to biodynamic farmer, he advised to start out slowly. Incorporate a few aspects of the practice at a time rather than trying to take it all on at once. When Federico started he only sprayed 500. Because we don’t live in a vacuum, and as an Evergreen student I like to look for as many intersections between subjects as possible, this is great advice for almost any major transition you make in life. If you want something to last and to work it’s unrealistic to completely change your lifestyle, or career, or whatever and expect those changes to continue for the long haul. Take small steps and you will learn more, be less frustrated, and have a more fruitful payoff in the end.

Spending time in the kitchen with Elena and at the table with the family, farm workers, and friends was of equal importance to my experience. I have so many new ideas on what to cook for myself and friends in the future, which I plan to do a lot of once I return. Here are a few ideas rolling around in my head: rice cooked in broth with vegetables is definitely on the list, and also lasagna! I think I should be able to cook a pretty solid ragù, which was a base for so many dishes. I love how there is usually some sort of frittata as a side dish, and simply steamed vegetables, especially beets, they love beets and chard. Though I haven’t yet made this, I want to try to make their version of a “cake” which is more like a pie, but instead of fresh fruit they use jam, or marmalade as they call it in Italy.

Clearly, I’m feeling inspired. I asked Elena when she learned how to cook, and she said it was when they started the agrotourism business. She followed that up with saying that the food is not as important as the table, meaning eating at the table with her family and friends. How lovely and perfect of a sentiment.

Something completely unexpected that I learned was that I really like children. I’m not around children that often, I was the youngest in my family, and it’s not as though I didn’t like them before I just didn’t know what to do with them. Maybe having a language barrier helped, but I had so much fun with their children. Chloé was the oldest (8), followed by Tideg (6), Anaïs (5), and Yèsa (5 months). They all had such distinct personalities, and if I’m being honest they could get out of control, one of them usually had a meltdown during dinner, and the joke of the family was that the one word I learned in Italian was “basta”, which means “stop/that’s enough” because I had to say it to the children quite a few times. Regardless of the chaos, they were so sweet and fun, you can’t expect for children to always behave, they’re little humans that are learning how to exist in the world, and it was wonderful to see these kids being kids. Elena didn’t rely on television to distract them, they played outside, Chloé was reading most of the time, they went for walks, and they colored in coloring books. I miss them so much, and I hope I can go back when they’re older, and when I know more Italian than “basta.” As Elena pointed out, children are hugely important to farming. Carlo Petrini talks extensively about the Slow Food initiatives on teaching children about the importance of food and flavor. And of course we all know that children are the future.

In summation, I loved my time at Nico. I’m so grateful for their hospitality and willingness to teach me about farming and food culture in Italy. I hope that one day I can return to their farm, or maybe Federico and his family will come to Oregon, he does know a lot of people there now. I chose both, please!

For now, I forge ahead on my journey through Toscana and continue to learn about (and hopefully adopt) the envious way of Italian living and dining!

Ciao ciao for now!

Mid Quarter Self Evaluation

I’m posting my self evaluation early because I’m not certain that I will be able to use my computer for the next three weeks. HERE is the link to my google doc for my self evaluation.

Bella Lucca

One of the many reasons that makes Toscana so beautiful is the sense of pride that people have about their region. Here, everyone talks about how beautiful the city of Lucca is, and they are not wrong. The city center is surrounded by a huge wall, was built about 500 hundred years ago, which was not the first wall to be built here. The first wall was built by the Romans, and the ancient remains are still preserved within the city. Lucca is an ancient and medieval city that was founded by Etruscans, which were a rich and powerful civilization of ancient Italy, and it became a Roman colony in 180 B.C.

Inside the walls of modern day Lucca there are many privately owned shops and restaurants, along with some chain clothing stores on the main street. You can walk around the entire wall in maybe an hour (I’m not exactly sure, I wasn’t timing because it was busy sighing at all of the beautiful things), and there’s also a botanical garden in one area. Every street is gorgeous and looks like the real life version of a postcard of Toscana. Though there are a lot of people out and about on a Saturday, it doesn’t feel overwhelming like it can in a larger city like Firenze. I suggest stopping at a café in the morning for a pastry and an espresso, followed by a walk around the wall, take a look at the tower guinigi, which has trees on the top, Chiesa di San Michele in Foro is a beautiful cathedral in the center of town, have lunch at the slow food restaurant Il Mecenate where the owner graciously walks around and checks on his guests (their pasta is amazing, and so is their house red wine), perhaps finish the meal off with the traditional cake buccellato before taking another walk around the town.

Changing gears back to the history of this area, from the year 1118-1799 Lucca was an independent province. In 1805 Napoleon conquered this area and made his sister, Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi the princess. Elisa ruled from 1805 until the fall of Napoleon’s empire in 1814. On an incredibly sunny Saturday, after visiting the farmers market in Marlia (a town in the province of Lucca) Federico told me I should go to see one of the Villas in the area, which lead me to Villa Reale. This Villa has roots tracing back to the medieval age, beginning as a fortress for the Duke of Tuscia. Over the years the property changed hands from wealthy family to wealthy family with new additions and a baroque style added to the park. In 1806 princess Elisa took a great liking to this beautiful Villa and purchased it, which is when it was named Villa Reale (reale meaning royal.) She made her own modifications, adding statues, giving a more English style garden, and other modifications that were in vogue at the time. Alas, in 1814 she had to leave her beautiful Villa behind when Napoleon’s empire crumbled. After that some other rich people owned it and it was used to throw parties that their rich friends attended and over time the Villa became neglected. In 2015 a Swiss couple bought the property and now you can pay 9 euros to walk around this lovely estate. I highly recommend spending part of a late morning here if you’re in the area. After I suggest taking a 20-minute walk up the hill, passing vineyards and olive trees with a lovely view overlooking the province of Lucca, until you get to the restaurant Osteria Il Botteghino. It’s nothing fancy, the menu is read to you by your server who doesn’t really speak English, but the food is great and you get an affordable three course lunch, which is perfect after all of that walking.

I love Lucca and I love how much everyone here loves Lucca. If you’re ever in Toscana, I highly recommend stopping here for at least a day to explore the city, and maybe more if you can see some of the surrounding villages in the province.

Lunar Calendar Planting

Farmers have planted based on the moon cycle for thousands of years, so this aspect of biodynamic farming (along with many other aspects) isn’t unique, but it is heavily emphasized, and the position of the zodiac signs are also considered when doing anything on the farm or in your garden. Along with the burying of animal parts, this is probably where people start raising their eyebrows and thinking this practice get into the witchy and new age spirituality category with healing stones and ayurvedic spas (not that anything is wrong with those practices, do what feels right for you.) Maybe it’s because I’ve lived in Olympia where talking about your sun, moon, and rising sign is a casual conversation, but I don’t think that how biodynamic farmers look to the stars for guidance is that weird.

You can get really into planting by the cosmos, such as when certain planets are in conjunction, but Federico hasn’t really talked much about that, so if you are dying to know about all of the intricacies of the positions of the planets and what that means for your crops I suggests referring to Wolf D. Strol’s Culture and Horticulture: The Classic Guide to Biodynamic and Organic Gardening where there is a whole chapter dedicated to all things celestial. Federico says that the most important thing to consider is where the moon is in the sky in relation to the sun. More than anything you don’t want to plant when the moon is at the top of the north node, it’s better to plant before or after that day. When the moon is rising it’s good to sow seeds and when the moon is descending it’s best to prune trees.

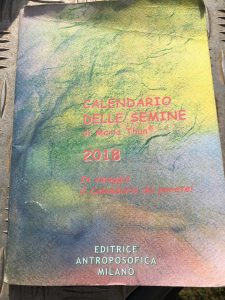

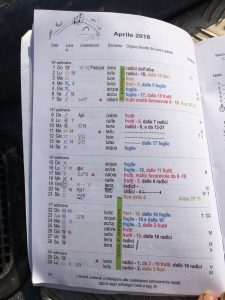

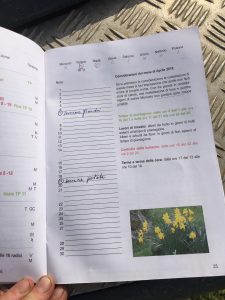

The next thing to consider is what sign the moon is in to know what will be best to plant during that time. If the moon is in an Earth sign (Tarus, Virgo, and Capricorn) it’s best to plant root crops, Air signs (Gemini, Libra, and Aquarius) are best for flowers, Water signs (Cancer, Scorpio, and Pices) are best for leaf crops, and Fire signs (Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius) are best for fruit crops. Federico uses the book Calendario Delle Semine by Maria Thun, which tells you the position of the moon and the sign it is in for each day. This booklet also provides a section to write down what you did that day to refer back to later. You can order Maria Thun’s booklet onlie and it is available in multiple languages including English. I did find a website that gives a less detailed description of the moon calendar online, the graphic design reminds me of the mid-nineties, early two-thousands websites and I love it, here’s the link if you want to check it out.

Paying attention to the moon and the zodiac positions is yet another part of what make biodynamic farming more involved than a lot of other styles of farming. There has been a little bit of research done on the effects of following these planting guides, but it doesn’t seem like there has been enough to make a blanket statement that these methods work. Biodynamic farmers will say that it does, so I think that counts for something. Though, it is very important to mention the right weather conditions will overshadow the lunar position of that day. That is, if it’s been raining relentlessly and you finally have a sunny day to plant, it doesn’t matter if the moon is at its north node, you should definitely plant those babies while you can.

A Chain Restaurant that Gets It

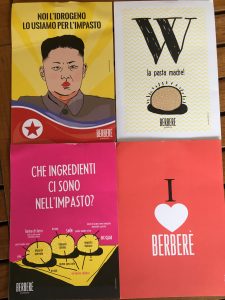

After the Fierucola market, Robin and Irene were so excited to take me to their favorite pizza place in Firenze. They even called ahead to make sure we could get a table. The reason why they love this place so much is because their crust is sourdough and whole grain, while the toppings are all sourced from local farmers. Okay, yes, I like what I’m hearing. The one odd thing to me was that this pizza place was not only their favorite in Firenze, but also in Milano, where they first experienced this amazing pizza. The name of the restaurant is Berberè, and it’s a chain restaurant, which is incredibly uncommon in Italy. Robin and Irene said that chain restaurants don’t really exist outside of fast food, which I wasn’t surprised by, maybe it’s a stereotype, but when I imagine Italy I think of a small, cozy restaurant that has been owned by the same family for generations and the have a secret pasta recipe, or something like that.

Berberè first opened in 2010 in Castel Maggiore and over the past eight years they have opened a restaurant in Bologna, Florence, Turin, Milan, Rome, Verona, and became international in 2017 when they opened up shop in London. They are passionate about exploring traditional ways of bread making, sourcing local ingredients, and progressing the deliciousness of pizza that one thinks of when they think of Italy by enhancing the quality.

Irene was telling me how there are so many small pizza shops throughout Italy that are terrible, she likes how fluffy the crust is compared to the flat, flavorless white crust that is very commonly found throughout the country. I can attest to this statement, having had a very disappointing pizza in a small village outside of Lucca. Berberè’s pizza was outstanding, the dough was so flavorful, and they also offered very interesting toppings, such as puréed peas as a substitute for tomato sauce.

Additionally, Berberè’s locations are all in historic districts, where the architecture is very unique and beautiful. They hire the same artist to paint illustrations on the walls, which incorporate the building’s structure into the art pieces. The importance of aesthetics cannot be denied when creating a pleasurable dining experience, and again Berberè gets it right. They have some “literature” made by artists that you can pick up on your way out as well.

If you’re ever visiting one of these cities in Italy and craving pizza, I recommend going to Berberè. Don’t let the fact that it’s a chain concern you because it’s not like an American chain at all. Yet another example of something I would like to see adopted in the United States, in a country where chain restaurants are a part of our culture, why shouldn’t there be chains that think about locally sourced ingredients and incorporating cultural traditions?

Fierucola

FIerucola is a market that takes place at the Piazza SS Annunziata in Firenze every third Sunday of the month. It looks like most typical farmer’s markets with vegetable, mushroom, jam makers, other value-added products, and local artist vendors, but its origins are a little more anarchist than the generally regulated markets you’re used to going to on the weekend. The Fierucola del Pane Association was started in December of 1984 to push back against industrial agriculture. It was started as way for peasants to build a community to support one another and their products, inviting participants who believe in small family farms, local farms, and non-entrepreneurs to help rebuild Italian rurality.

I was shown this market by a friend of Lane Selman’s, Robin Morgan. Robin has been studying agriculture at the University of Pisa, specifically looking at breeding lines of spelt. He and his partner Irene, who is now studying herbalism, but who has worked as a pastry chef in Michelin starred restaurants, were kind enough to show me the best stops at this market.

When we first arrived we talked to Paolo, he and his father Pierluigi started the organization called Piante Innovative in 2008. Both father and son have had a deep passion for seeds and the stories behind them. They collected and cultivated uncommon plants and in 2010 Paolo set out to spread the word of these seed throughout Toscana. Paolo is incredibly passionate collecting and distributing seed as well as all of the history behind the seeds. During our discussion, I was constantly nodding my head and saying “si” (even though he was speaking English, I try to use the ten words I know in Italian any chance I get) to his philosophy on food and art that comes with seed preservation. He helped me choose a few interesting plants to bring back with me. Here’s the list, I’ve translated what is listed on their website or the seed packed into English:

Acmell oleracea

Family: Compositae

Origin: South America; spread throughout the world

Characteristics: small upright plant, of rapid growth very decorative due to the curious and numerous red-yellow inflorescences.

Cultivation: prefers drained and Humus-rich soils with widespread humidity; full sun or partial shade. It is sown in May with temperatures of at least 18 ° C; it is perennial in mild climates or if protected from the cold. The plant spreads with its characteristic inflorescence, it fears snails attacks.

Therapeutic value: L ‘ Acmella oleracea has mucolytic action, promotes digestion and has an anesthetic effect; the decoction or infusion of leaves and flowers is a traditional remedy for stuttering, toothache and stomatitis; chewing leaves and flowers strengthens the gums, soothes toothache and refreshes the throat; an extract made with this plant should visibly and quickly reduce facial wrinkles. In many countries, this plant is also used effectively in cases of bronchitis, burns, headaches, migraines and itching.

Edibility: it is a valid alternative to the most common and tasty spices; the particular fresh and “spicy” sensation for lips and palate caused by the leaves and flowers in the shape of the button just picked up gives it a unique taste; thanks to its spicy aroma, this spicy herb is suitable for soups, salads or special vegetable side dishes. If cooked, the leaves lose part of their spicy flavor and can be used as vegetables. In Brazil it is used combined with chili and garlic to enrich other dishes with flavor and vitamins. The flower alone has a grassy taste immediately followed by an almost electric tingling and excessive salivation; in India flowers are used together with chewing tobacco.

History: the vulgar name seems to derive from the Brazilian province Para, a term that is taken up in almost all the vulgar names given to this plant also abroad. It is unbelievable that the plant is completely unknown as a spice outside of Brazil and neighboring countries. For the kitchen, this innovative herb can be an interesting alternative to spicy spices that are used in western cuisine. Since 2000 this plant is subject to careful studies because of its many and particular substances used in many recipes, studies and medicinal preparations; noteworthy is the spilantolo which stimulates the receptor in the oral cavity responsible for salivation. An effective insecticide has been produced for many decades by the concentrated extracts of this plant.

Cucurbita ficifolia

“7 year old pumpkin, siamese, pumpkin, fig leaf pumpkin, chilacayote”

Family: Cucurbitacea

Origin: Mexico

Characteristics: perennial climber with rapid growth and late fructification, resistant to cold, but not to frost. Monomic flowers pollinated by insects. Self-fertile species.

Cultivation: it thrives in rich and well drained soils and in bright and sheltered warm locations, but tolerates many conditions and is well suited even in poor soils. In temperate climates it is cultivated as annual. Plant very vigorous, can reach several meters in length climbing trees and nets, sometimes exceeding 15-20 meters in a single year. The plant follows the photoperiod and flowers at the end of summer, arriving to ripen the fruit in late autumn. Does not hybridize with other members of its kind.

Therapeutic value: the seeds are vermifugos; they are used together with the shell. They are minced and reduced to powder, then emulsified with a little water and eaten. As a remedy for internal parasites, the seeds are less potent than the root of Dryopteris filixmas, but they are safer for pregnant women, debilitated patients and children. After a possible treatment, it seems necessary to take a purge to expel the parasites from the body.

Edibility: often the fruits are consumed young, still green, raw or cooked; excellent if sautéed or sautéed like zucchini to season pasta and omelets; raw are used in salads like cucumbers, but they are tastier. The ripe fruits that are not very useful in savory dishes are very suitable for making jams and candied. The sugar is added to the pulp, and during the cooking the consistency becomes stringy and fragrant. The ripe fruits can be stored for 2 years or more and become sweeter with storage. It is one of the most productive and consumed pumpkins in the hot countries of the world. In Ecuador, you make a juice called zambo. The seed is rich in oil with a nutty flavor, but difficult to extract given its fibrous layer; excellent toasted and consumed like a peanut. Also from the seeds you get an edible oil rich in oleic acid.

History: The story tells that this type of pumpkin arrived in France at the beginning of the twentieth century, precisely at the “jardin du plantes” directly from Mongolia, along with the first yaks ever seen in Europe. Given its shelf life this fruit was used as food for animals during the long journey made. The spread of this plant in Europe came as a result of this event. Rustic pumpkin, which takes its name from its leaves in the shape of fig leaves; the fruit of a color similar to watermelon is characterized by a strong rind that makes it durable (up to 7 years) and resistant to rotting. It stands out for its strength of growth with vigorous shoots, and high productivity. It is an excellent rootstock of Cucumis sativus (cucumber) giving it more vigor, productivity and resistance to disease. This species is the most robust of its kind and does not naturally hybridize with other pumpkins (although cross-breeding can be obtained under controlled conditions). In America, it takes 3 months from the seed to the first harvest and 6 months to get ripe fruit. The shell of ripe fruit is very hard and can be used as a container.

BASELLA rubra- BASELLA alba

“Spinach of Malabar, spinach runner or creep”

Family: Basellaceae

Origin: Asia, Africa

Habitat: wet places

Characteristics: perennial climbing plant, with cuneiform or heart-shaped fleshy and waxed leaves that can quickly reach 9 m in height in the country of origin (in the Mediterranean climate it reaches heights of 2-3 m); it blooms from May to September and the flowers are hermaphrodites. The alba variety has white flowers and green leaves, the rubra has purple flowers and reddish leaves. The plants are photosensitive and bloom with a duration of less than 13 hours; fear frost;

Cultivation: suitable for all types of soil as long as they are well drained, Basella is easy to grow and loves bright and fresh soil, it also tolerates acid soils and very rainy seasons. It grows well with temperatures above 15 ° C, provide the plant with a support where to climb. Due to its rapidly growing nature it can reach full development already after 70 days from sowing; can winter in cold greenhouses maintaining temperatures higher than 0 thermal; in winter, you can protect these plants in the ground with manure or organic material placed at the foot of the plant.

Therapeutic value: The roots are astringent, while the mucilage present in the leaves and stems refreshes and improves intestinal functions; Flowers are used as an antidote to poisons. The whole plant has a febrifuge, diuretic and laxative action; the decoction of the leaves can alleviate the pains of women in labor; the juice of the leaves has an emollient action, used in cases of dysentery. The leaf juice is used in Nepal for the treatment of phlegm. From the leaves is obtained a cream useful for soothe eczema and skin irritations.

Edibility: it is an excellent substitute for spinach during the hot season. It offers, in relation to the land occupied, an abundant production of leaves and young jets with a sweet taste to be eaten raw in salads or as a side dish. The mucilaginous qualities of the plant and its stems make it an excellent thickening and gelatinous agent in soups, sauces , stewed, etc. where it can be used as an alternative to all’okra (Abelmoschus esculentus). From the nutritional point of view it is rich in Vit. C, Vit. A, iron, calcium and chlorophyll; it is low in calories. A good tea is obtained from the infusion of the leaves; the juice of the small and numerous fruits that surround and protect the seeds provide a ruby red color used as a food coloring for desserts and dishes.

History: the red dye obtained from fruit juice has also been used as a dye for lipsticks and as a dye for seals, and as a watercolor. Vegetable in all respects is presented in the rubra variety also as a decorative plant, if popped during the vegetative phase increases the preparation and the production of leaves, it is a vertical vegetable therefore also excellent for terraces and balconies. In order not to ruin the qualities of this vegetable, cooking must always be very fast.

CUCUMIS melo

Tiger Melon, Kajari melon

Sowing: April

Exposure: full sun

Soil: rich and well drained

History: It is a fragrant and very decorative melon. Externally it presents yellow and orange stripes reminiscent of the tiger mantle. The pulp is white or light yellow and has a very sweet taste. This variety, originally from India and known as Kajari melon, was very famous and appreciated in England during the Victorian period where the fruit was used as a deodorant for the rooms and linen. The women used the fruit hidden in their robes or in their handbags to enchant men and suitors with their almost aphrodisiac fragrance. This variety very resistant to diseases and the fruits are small to medium in size. It takes 70 days for them to produce fruit.

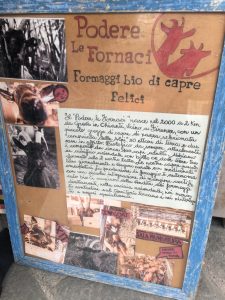

Aside from seeds, I also bought some goat cheese from the farm Podere le Fornaci, a goat farm outside of Greve in Chianti. At the market they sometimes offer specials, Robin told me in the past they had an adopt a goat program, where you could buy 100 euros worth of goat cheese and you’d get an extra 10 euros as a bonus. The farm said that it was a 10% interest return, which was better than any bank could offer you. On this day, they were offering a free hug if you spent 30 euros or more. The goat cheese was fantastic, and was definitely worth some of it leaking into my backpack on the train ride back to Lucca.

Finally, I picked up a loaf of beautifully baked, whole wheat bread from Panis Vita. They grow the grain, mill it, and bake the bread. They offer a few different types of bread, one had anise seeds, another was baked with raisins, there was a spelt made bread, but I went with the whole wheat because it’s a classic that can be eaten with jam or smothered in olive oil during dinner. Locally grown, milled, and baked whole grain breads are slowly becoming popular in the United States through various initiatives and it’s something that everyone should be excited about. It’s good for the earth, good for producers, good for bakers, good for your body, and good for your palate.

Another day full of seeing people who care about food and another day that inspires me to keep learning, listening, and growing.