Left and right my dreams are coming to fruition in Italy. The dream I’m talking about today is my dream of someone teaching me how to cook, and what’s more is that the person I am learning from is a Toscana woman.

For some context here’s a little background about myself, I come from medium sized town in the middle of nowhere Washington. A place referred to as the Tri-Cities, but I hail specifically from Richland. It’s a typical suburban American town, picture and endless row fast food, strip malls, and chain restaurants, where Italian food is Olive Garden and Chinese food is P.F. Chang’s. Outside of these stereotypical American infrastructures lies acres upon acres of farm land, almost exclusively conventional. Though in Katherine Cole’s book Voodoo Vintner she did mention a biodynamic vineyard in the Tri-Cities, which I am very impressed to hear. My father was a conventional farmer of alfalfa sometimes corn in addition to a herd of cattle and my uncles are cherry farmers. I’ve always known that farming is hard work, and that food doesn’t just magically appear from a grocery store. Even though my family grew food, cooking was not something that we did together. I ate a lot of bland food, maybe some tuna helper, steak, potatoes, again I feel like a bit of an American stereotype. I’m definitely not blaming my parents for not instilling a love for food on a deep cultural level because I can’t think of anyone of my friend’s families that were food centric, unless they were hiding it from me.

I started caring about food and thinking about it in the context of culture in my early twenties thanks to an ex of mine. We would spend our weekends watching Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations while he cooked and I sat on the counter occasionally stirring something. Remember I had never cooked anything before, the best I could do was assemble a sandwich. I eventually moved to Portland and was exposed to the restaurant scene there, I worked as a server for a little bit at a small bistro, then started working in specialty coffee at Extracto in NE Portland, which is surrounded by amazing restaurants such as Beast, DOC, Pok Pok Noi, and Grain and Gristle to name a few. There is no avoiding good food, hip restaurants, and food sourcing in Portland, and really why would you want to? It’s a cornucopia of localvores. May it live on forever.

Inspired by the community of food lovers and chefs that I became a part of I eventually taught myself how to cook very simple dishes. Learning how to sauté vegetables elicited both a sense of pride and embarrassment for not knowing this simple act sooner. I fell in love with how food brings people together, the excitement of feeding people, how cooking with people can be a fun activity to do with friends, and sitting down at a table to enjoy the labor of love. All of the things that so many food movements talk about I was feeling.

Even though I can sort of navigate my way around a kitchen, and cooking isn’t quite as scary to me as it once was, I’ve been longing for someone to teach me a few skills through hands on experience rather than someone giving me a verbal tip. I hope through my long-winded story of my food journey you understand how excited I am to spend four weeks helping Elena prepare meals.

For a typical dinner that serves about eight people, Elena will start cooking around 4:30 or 5:30 pm. It takes around three hours to prepare everything, but that includes the time it takes to stop and feed her five-month-old, or attend to her other three children. Also, she makes a lot of food, so there are usually leftovers that will be eaten for lunch the next day or two.

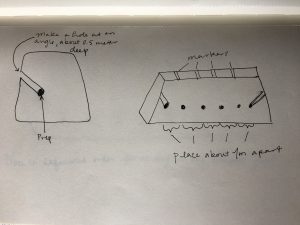

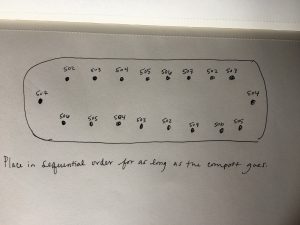

The following pictures are us preparing a rice dish. First, we make a simple broth (brodo) with one potato, two carrots, and onion, fresh herbs from her garden, olive oil, and salt. Let that simmer for about an hour. In the meantime, cut the vegetables that will go into the rice. It’s spring time right now so we’re using asparagus, artichokes, zucchini, and zucchini blossoms. You want to set the tips of the asparagus aside to be quickly sautéed right before serving, the zucchini and the blossoms are also set aside until closer to the end because they’re softer and will cook faster.

Elena is also preparing a chickpea tart type dish, using 100 grams of chickpea flower and 300 grams of water, an unspecified amount of olive oil (Elena just said a lot), salt, finely ground pepper, and herbs. That’s baked in the oven for about thirty minutes and is incredibly delicious with a soft, yet crisp texture.

After an hour of simmering the broth is ready to be used. Elena cooks her rice in broth, HOW HAVE I NEVER KNOWN TO DO THIS BEFORE?! After learning this I understood why her rice had so much more flavor compared to most rice I’ve had in my life. We then add the artichokes, asparagus ends, and carrots to the pot. Once the rice has almost finished cooking we add the zucchini and blossoms as well as a little bit of cream, a lot of olive oil, and some salt.

Most of my meals here have been vegetarian, not a lot of meat is consumed. Maybe once a week we’ll have chicken, or a delicious roast beef smothered in a very mild mustard, but really, it’s all about vegetables. The vegetables are steamed and then doused in olive oil and a little salt. I’ve decided that I need a pressure steamer when I return, it’s been very convenient for root vegetables such as beets, and also for tougher vegetables such as artichokes. Beans would be another reason for a pressure cooker. They also eat raw vegetables, at lunch and dinner there is always a salad which is just lettuce, maybe arugula, then add olive oil and salt. Done.

This evening we also prepared the sauce that would be used for the follow night’s lasagna. I minced carrots, onion, and celery together, which was slowly sautéed in olive oil. This lasagna was to be vegetarian so Elena used lentils instead of meat. Add the lentils and let that simmer for a while and you have yourself a delicious sauce for lasagna, or to put over pasta.

I’ve also noticed that there isn’t a lot of food waste happening at Nico. First, Elena uses the vegetables that Federico doesn’t sell at the market, the vegetables that might not look like what we’ve been conditioned to see at the grocery store, but are still as delicious and nutritious as the better-looking counterparts. Because they are also running an agrotourism business Elena is cooking for guests often, and there are often leftovers, which are then taken to her house and eaten for lunch and dinners until they are gone. Elena only makes a new dinner for guests or if her family and the other workers on the farm have eaten all of the leftovers. This is what living in a perfect food world is like.

In summation, I’m learning that you really don’t need to do anything fancy to make a delicious meal. Having good ingredients is essential, the liberal use of olive oil helps a lot, and adding a few herbs from your garden is ideal. Also, cook everything that you can in a broth!