This is an introduction to how biochar may be used to improve sustainable food production and provide income diversification for the families of Bangladesh. The main difficulties of utilizing biochar is the shortage of biomass and the large population that has limited disposable income. One approach is to make biochar as a by-product of cooking with gasifier stoves, then use the biochar with composts and manures in homestead gardening and in small agricultural businesses . The ultimate goal is to increase food security for a people facing strong consequences of climate change like erosion, carbon sequestration, and ecological restoration.

The Akha is a wood-burning cookstove has been developed by the Bangladesh Biochar Initiative. It is clean-burning, fuel-efficient, and produces a constant heat without stoking. However, what really sets the Akha apart from other biomass cookstoves its ability to make biochar at the same time as cooking. Producing char maximizes the utility of the wood, because we can get more energy if we burn the char as charcoal, or we can increase agricultural productivity if we use the char as biochar. The Akha is the only sustainable way of generating practical quantities of biochar for households.

The Akha is a semi-permanent installation that can be easily disassembled and moved. The essential components are a fuel cylinder (reaction chamber) and a gas burner on top that supports a cooking pot. There is also base that contains an air flow regulator, and a trap-door grate for removing char from the bottom of the fuel cylinder. The operator loads the fuel cylinder with small pieces of wood, then lights the fuel at the top. The Akha works by burning a batch of fuel from top to bottom, using a small amount of air supplied through the grate at the bottom of the fuel cylinder (Video). As the fire moves down through the fuel it produces a lot of smoke. The smoke is flammable. It rises out of the fuel cylinder, and is burned in the gas burner. No smoke exits the stove, and the emissions of soot and carbon monoxide are very low. Heat production is steady, because the fire moves down at a constant rate through the fuel. Women say that the experience is a like cooking on a gas stove. When the fire reaches the bottom of the fuel cylinder, the flame in the gas burner goes out, and cooking stops. Inside the fuel cylinder the char remains red-hot. The char can be safely removed via the trap-door grate, and quenched in water or suffocated (Video). At this point, the Akha can be reloaded with fuel and re-ignited. Depending on the type of wood, and the height of fuel in the cylinder, and air supply through the grate, the Akha can burn for 15 minutes to almost one hour.

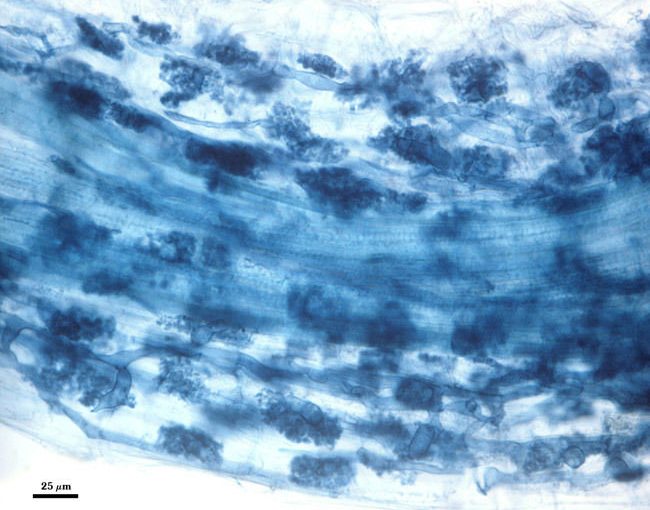

The Akha is a type of natural draft (ND), top-lit updraft gasifier (TLUD). ND-TLUD technology was pioneered for cooking with the “Peko-Pe” stove by Paal Wendelbo, and the “Champion” stove by Paul Anderson. After a fuel is ignited at the top, the fire moves down, as an ignition front, toward the grate at the bottom of the fuel cylinder. This ignition front is also called a ‘migratory flaming pyrolytic front’ (MFPF). The temperature in the MFPF ranges from 550 to 1200 °C, with higher temperatures for coarser pieces of wood fuel. The typical temperature is around 650 – 800 °C. When wood is heated above 300 °C, it under goes a type of thermal decomposition called ‘pyrolysis’. There are two main products of wood pyrolysis: volatile gases (‘smoke’) and char. The volatiles contain combustible gases (CO, H2, CH4) and tars. These are burned above the fuel cylinder in a simple gas burner that creates a flame just below the cooking pot. Unlike in an ordinary combustion stove where everything burns together, the TLUD is able to vertically separate the burning of volatile smoke from the pyrolysis of wood and burning of char. The gas burner is able to optimize conditions for the burning of volatiles, which is why polluting emissions from a TLUD are very low. Not much char is burned in the fuel cylinder, because the air flow through the grate is not fast enough. Thus, when wood pyrolysis is finished, about 15-25% of the original dry weight of wood fuel remains as char.

The best kind of fuel is short pieces of wood about 1-2 cm thick. These, when placed into the fuel cylinder, form a fuel bed containing air spaces through which air flows upward from the grate, and volatiles flow out to the gas burner. The energy efficiency of this type of TLUD is 30-35%. If the char is burned in a charcoal stove, the total energy efficiency can be over 50%. The wood should be dried to < 20% moisture. If the wood is too damp, the produced volatiles will not burn. The Akha will burn nut shells, broken rice-hull briquettes, and wood pellets, but is not designed to burn low density fuels such as leaves or rice straw.

All TLUDs should be operated in well-ventilated conditions, because the emission of small soot particles—although very low—are not zero.

For households, the advantages of the Akha are being able to cook efficiently, smoke-free, and make char. The Akha can operate unattended. As mentioned above, char production is a major benefit, because it will maximize the use of the wood, and is a keystone product for other household enterprises involving charcoal and biochar. By making char, the household can save money, and/or generate revenue. The main disadvantages of the Akha are (1) having to prepare small pieces of dry wood, (2) having to reload fuel for long jobs, and (3) having to learn how to use a TLUD properly, because if gas fire goes out, there will be a lot of smoke. However, learning to use the Akha is not difficult, and the benefits will outweigh the limitations. Recently, the Akha was evaluated by households in Manikganj, Naogaon and Dinajpur. The women who tested the Akha greeted it with enthusiasm. Improved models of the Akha are being developed based on household reviews and scientific testing.