Due to travels and scheduling conflicts, this weekend was sadly my last at Olympic Yarn & Fiber. So, we tried to pack it full of as much information as possible! We started off with Lynn showing me the basics of fiber sorting. It’s actually such an exact science that it can be incredibly difficult to do by eye since the micron count of fiber can vary so slightly. But, it’s still possible to get a good idea of the fiber grade that you are working with by both sight and feel.

Fiber “grade” describes the micron count of a piece of fiber – that makes up the width and weight. The lower the grade, the finer the fiber and, consequently, the yarn. I learned that it is important to sort your fibers to be within a couple grades of each other because our bodies can detect discrepancies in the materials we put on us, thus, causing discomfort. In order to “eye sort” the fiber, it is important to have both a black surface and a white surface. For black fiber, you hold it over a white piece of paper and stretch it out. The contrast between the black and the white makes it so that you can see each individual piece which allows you to get a sense of how it would be sorted.

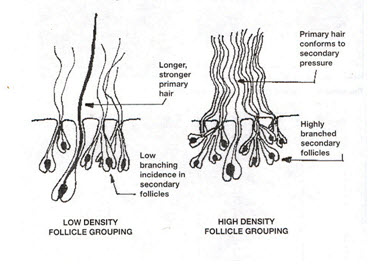

I learned most valuable animals have a pretty consistently low grade all over their bodies – this is especially true of alpacas since they have been bred with this in mind. Animals like goats and sheep often have “guard hairs” which are thicker, stronger and less present fibers that can bring down the quality of yarn unless they are taken out. Alpaca, however, no longer have guard hairs due to selective breeding and now simply have secondary hairs (finer) and primary hairs (what used to be guard hairs). The most high quality alpaca fiber will have primary and secondary hairs that are nearly indistinguishable.

After we sorted some fiber, we walked around the pastures and talked briefly about pasture management strategies. I learned that alfalfa is oftentimes the highest cost in keeping alpaca since they consume so much in a day, so keeping pastures as green as possible for as long as possible is a top priority. This year, Lynn has a sprinkler system running and will be applying compost tea in order to help keep the alpaca off of pre-purchased food as long as possible. I also learned that in order to help keep fiber quality as high as possible, some owners will often opt to rake up various different sticks and pinecones in order to prevent them from getting tangled in the animals’ hair.

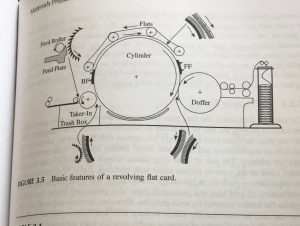

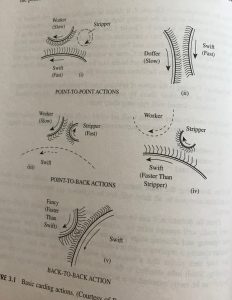

I’m pretty sad to see my time with Olympic Yarn & Fiber end, but I am happy to say that I’ve come out of this internship with a ton of new knowledge regarding fiber milling and animal husbandry. At the beginning of the quarter, I began with only basic knowledge of how yarn mills ran. But now, I can identify every piece of equipment and have a fundamental understanding of how they work/how to operate them.