This article discusses the role of extrafloral nectaries on the life cycle of Chrysoperla plorabunda, a common generalist predator. Ideally it could be a potential predator of the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii. The article notes that although natural densities of lacewing eggs are high in cotton fields, biological control is usually somewhat poor, with larval stages appearing to be rare. Apparently, lacewing larvae are subject to predation from many hemipteran predators. Typically low larvae populations are associated with food scarcity. This article observes how lacewing larvae are influenced by extrafloral nectaries.

Results

Neonate Larvae

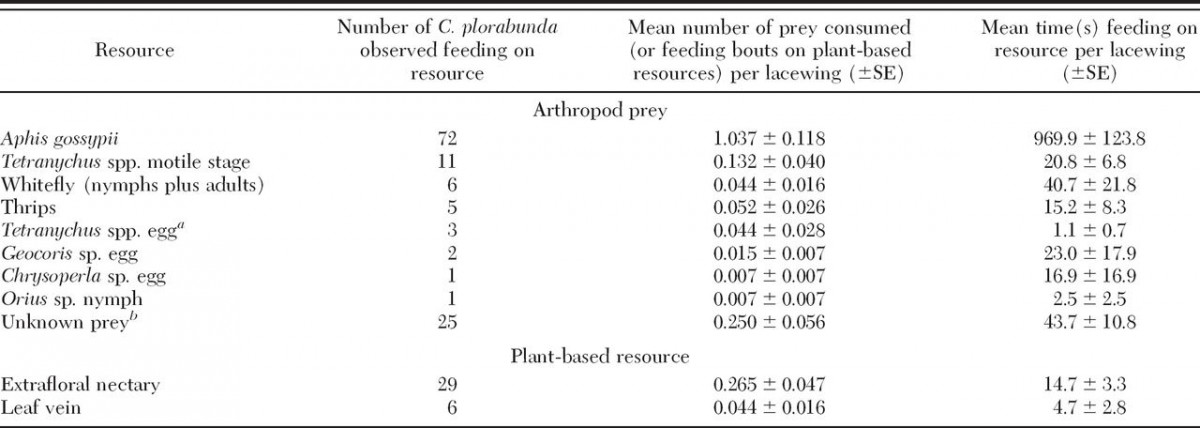

The primary food eaten by the neonate lacewing larvae was soft bodied arthropods, both herbivorous and omnivorous. 21.3% of the larvae consumed extrafloral nectar during their observation, usually from foliar nectaries, but occasionally from circumbracteal nectaries (I believe this means nectaries beneath the flowers). Some lacewing larvae even inserted their mandibles into leaf veins.

The time spent visiting extrafloral nectaries was inversely correlated with the density of aphids on the first contacted leaf, indicating that the larvae will shift to extrafloral nectaries if prey is unavailable. At first, this could be explained by active foraging decrease simply because there were more aphids that were easier to find. They also hypothesized that larvae who consume aphids may reject nectaries or take shorter feeding bouts. After analyzing their data, they found that aphid density didn’t cause significant variance. Rather, the amount of time spent foraging was the sole predictor of nectar feeding.

All Instar Larvae

1st, 2nd, and 3rd instars of lacewings were only observed feeding at an extrafloral nectary one time on cotton, while 7/11 consumed extrafloral nectar in almond orchards, indicating a preference for almond nectaries.

Field Diet Experiment

Lacewings were given access to plant leaves with different resources; some only had leaves, others water, then nectaries, as well as nectaries and aphids. What they found was a significant lengthening of neonate larval survival time when extrafloral nectaries were present. Without food, neonate larvae died with 1-2d, while those with access to nectaries lived up to 15 days.

Laboratory Diet Experiment

Larvae were given water, foliar extrafloral nectar, and brachtael extrafloral nectar. No larvae could pass the second instar on water or nectar diets, however those given nectar lasted significantly longer (4-6 days compared to 1). Bracteal extrafloral nectar allowed larvae to live significantly longer than foliar nectar, as well.

Conclusions

Neonate lacewing larvae, as well as later instars to some extent, use extrafloral nectaries as a supplemental source of nutrients. If there is a lack of prey, these nectaries may be able to support larvae for some amount of time, at least better than water.

The article hypothesizes (with some evidence) that the consumption of nectar was not a decision made by larvae, however it is more likely a result of secondary factors. Lacewings that have access to aphids and other prey have to spend less time searching and foraging, and therefore encounter extrafloral nectaries less often. If aphids are absent, the larvae will spend a significantly longer time foraging, and is thus likely to run into and consume extrafloral nectar.

Experiments have observed that significantly increasing aphid densities doesn’t necessarily enhance lacewing survival or development significantly, and lacewings can often achieve near maximal consumption rates on low populations of aphid (four per leaf). This raises questions on whether or not prey scarcity is the issue with low populations of lacewing larvae.

There are some sources of bias in this experiment as well – for example, nectar quality among nectaries on the same plant can vary, and nutrient quality of nectar varies during seasons as well.

Either way, this is good evidence that having plants with extrafloral nectaries in agriculture systems can assist beneficial insects throughout their life cycles. Additionally, they may provide a significant buffer if your pest presence is low – which is good, because if all your predators die when you have low pest populations they may not recover if pest populations begin to rise.