Much like a child flourishing in an environment rich with opportunity and gaining an appetite for success, the Oregon Grape (Mahonia Nervosa) as well as many plants increases its number of breathing holes (stomata) to take in more CO2 when it gets more sunlight.

At least that’s our hypothesis…

In a quest to evaluate how plants are being affected by our environment today, a group of two peers and I set out to measure stomatal density in In Oregon Grape leaves.

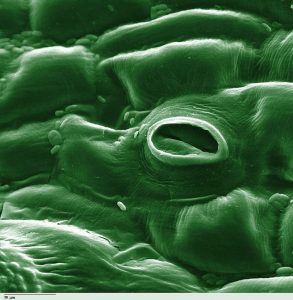

A stoma is a tiny pore on a plant leaf as seen to the left, and any given leaf likely has tons of these all over it. it needs so many of them because it uses these to breathe. when a plant makes the sugar it needs to survive it uses CO2, H2O and Light and the CO2 aspect of that is collected using these stomata. so stomatal density is simply how many of these stoma’s there are within a square millimeter of the leaf being examined.

At first we were very interested in how certain fungal diseases would affect the stomatal density of salal leaves but when we went and collected the data. It turned out that we couldn’t really see any any real trend. We also weren’t sure exactly how to set up that experiment,. we were stuck between options such as checking new growth alone in case stomata were only truly effected during leaf formation and instead just doing specific areas of the plant. on a similar note we had trouble telling how long a certain plant had been diseased compared to another and how intense it had become. overall that study became it a bit much to handle and so we swapped it out.

Now our Hypothesis centered around where a leaf was on the plant vertically. We chose this both because it was easier to choose a good sample with certainty, and because we had found research corroborating its significance online and hoped to be able to vaguely replicate those results. For our first set of data with this hypothesis we took two samples from the very top layer of leaves on the Tall Oregon Grape (Mahonia Aquifolium), two leaves directly below the first layer, and two leaves directly bellow the second samples layer. upon testing the difference in stomatal density between these layers we found no recognizable trend, and upon analyzing our data found that the randomness of stomata among each set outweighed any possible correlation we could have found. so for the second half of our data we decided to up the anty and increase the distance between the layers . Now we were taking leaves from the very top, the very bottom., and from the middle between those two locations. while our data showed slightly more of a true trend this time around, the randomness was still overpowering.

Possible error in our results would have to be from differences within the same plant rather than between sampled plants because I specifically had taken the ratio’s of stomatal density between layers only of individual plants such as tier 1/tier 2 and so on so that we wouldn’t have to worry about whether a certain environmental factor would majorly boost/inhibit the stomatal density of a specific plant. This way we were only measuring how different each plant was from itself not from one another. One possible source of error is how each tier of leaves formed when they were still newly grown. we don’t know exactly what coverage each tier would have had during its formation since we only saw them once they had matured. I’m taking this into account because A. P. Gay and R. G. Hurd had done a study on tomato stomatal density and found that new growth’s light exposure seemed to be the key most feature in determining stomatal density rather than environmental factors later in a plants life. so if for instance every single tier initially grew with none of the rest of the plant above it, then according to their study we wouldn’t expect to see any correlation to height on the plant because the affecting factor of upper tiers shading those below would have been entirely absent during the formative time of each tiers stomatal count. aside from this we have no data on how the canopy above may have changed throughout this plants life. for instance if a huge big leaf maple (Acer macrofolium) fell over during the life of one it might massively increase the number of stomata in the later layers given how much more light they had to feed on that the ones prior to the sudden canopy gap. (Gay, A. P. 1974)

Size of leaf in specific ought to be controlled within single plants. This should be controlled since it has been shown that leaf area is inversely correlated to stomatal density. Leaf Orientation however has been shown to be a non important factor, as it appears to have no effect on stomatal density.(Peel 2017)(Daly 2010)

stomatal conductance( how much CO2 can absorbed per second by a single stoma )could also effect the importance of our results. unfortunately we don’t have the tools to measure this available readily. Instead we will go along with the assumption that it stays virtually the same throughout a single plant. (More info on Stomatal Conductance)

If we were to do this again I would try to take into account the level of possible change in canopy such as if the plant were in the middle of a forest with lots of trees near death or where all of the over story is young and likely to live long. or in the middle of an open field were no change would likely be possible other than cloud cover which would affect all of our plants anyways.

Lacking in a larger significance from the diseases direct effect on plants we can still bring up the question of why the stomatal density is what it is and whether wed best help plants via increasing their stomata or improving their environment.

Bibliography:

- Peel, Joanne R., Mandujano Sánchez, María C., López Portillo, Jorge, Golubov, Jordan, Stomatal density, leaf area and plant size variation of Rhizophora mangle (Malpighiales: Rhizophoraceae) along a salinity gradient in the Mexican Caribbean. Revista de Biología Tropical [en linea] 2017, 65 (Junio-Sin mes) : [Fecha de consulta: 18 de mayo de 2018] Disponible en:<http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44950834022> ISSN 0034-7744

-

Daly, Rachel G, and Robert A Gastaldo. “THE EFFECT OF LEAF ORIENTATION TO SUNLIGHT ON STOMATAL PARAMETERS OF QUERCUS RUBRA AROUND THE BELGRADE LAKES, CENTRAL MAINE.” Palaios, vol. 25, 2010, pp. 339–346., doi:10.2110/palo.2009.p09-107r.

-

Minorsky, Peter. “Engineering Increased Stomatal Density in Rice.” Plantae, ASPB, 11 Dec. 2017, plantae.org/engineering-increased-stomatal-density-in-rice/.

- Gay, A. P., and R. G. Hurd. “The Influence of Light on Stomatal Density in the Tomato.”Nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com, 13 Nov. 1974, nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1975.tb01368.x

- Angelo Branco Camargo, Miguel, and Ricardo Antonio Marenco. “Density, Size and Distribution of Stomata in 35 Rainforest Tree Species in Central Amazonia.” Revista Brasileira De Hematologia e Hemoterapia, Associação Brasileira De Hematologia e Hemoterapia, www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0044-59672011000200004

Leave a Reply