A ten hour per week internship at Wingman Brewers in Tacoma, WA that occurred over the course of 10 weeks. I learned about the production process, ingredients, and fermentation.

~

Beginning to Brew

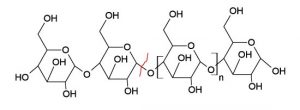

As I walked up the narrow steps of the steel kettle to greet Ken, I gazed around the room in awe and took in the sights and smells of the brewery. I loved the warmth radiating out of the huge steel vats and the earthy, sweet smell of malted barley that reminded me of time long past where spontaneous fermentation was commonplace. Before I could finish romanticizing about the brewery, Ken jumped into explaining the biological processes at work in the vat. Alpha and beta amylase, the same type of enzymes found in human saliva, break down the complex hydrocarbon chains into more simple sugars that are easier for the yeast to digest. Each version of amylase works best at different temperatures and breaks up the hydrocarbon chains in different ways. Alpha-amylase works best at 154-162F and beta works best between 131-150F. Ken mashes at a happy middle ground: 151 degrees. If a sweeter beer is desired, then you want to work in a temperature range more suited for beta-amylase, since it ‘clips’ off the ends of hydrocarbon chains, therefore shortening the chain. On the other hand, to have a more dry beer with less sugar you will want alpha-amylase to become more active since it will break up all the long hydrocarbon chains into shorter chains. These short chains are the easiest for yeast to digest and utilize.

alpha-amylase:

~

Lebanese Cedar

During my second week interning at Wingman Brewers, we all attempted something new: spontaneous fermentation. We were going back in time to discover what mysterious flavors microbes naturally occurring in the environment could create. It takes a lot of planning in order to do something like this; especially when you can’t rely on commercial yeasts and wild yeasts are so unpredictable. So while Ken and Pat figured out a lot of the specifics, I gave the log another wash and vacuumed it out. Why was I vacuuming out a giant log you may ask? Well this giant log was in fact lebanese cedar that was carved out and sanded down, to be used as the ‘cool ship’.

A ‘cool ship’ is “a type of fermentation vessel used in the production of beer. Traditionally, a coolship is a broad, open-top, flat vessel in which wort cools. The high surface to mass ratio allows for more efficient cooling.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coolship)

This giant log was the centerpiece of this whole operation, but there is more to spontaneous fermentation than the cool ship. Barley and unmalted wheat were used and this combination was incredibly thick and sticky. It smelled like your standard oatmeal and didn’t hold many surprises. The first batch of water was drained into the kettle (after vorlauf); this was done because it allowed the enzymes to be activated and removed, so the starches weren’t broken down too much. This allows there to be food for the yeast, but also some more complex food for the wild microbes. More water was added to the mash and this was let to sit for 2-3 hours at a higher temperature. (Some random hops were added to the kettle too.) After everything was drained into the kettle, the water was put into the cool ship overnight. In the morning, the liquid was moved to old oak barrels to ferment for a long yet unknown amount of time.

The Process Behind the Bottle

Making beer is not all fun and games, it takes precise measurements and requires all of your attention to be focused on time and temperatures. Aside from that though, making beer is actually pretty fun…at least in my opinion. The swirling of the malted barley in the water shimmers in the light and never fails to capture my attention, but I’m jumping ahead in the process and I should start at step one.

To start you want to fill the mash tun with hot water (168 degrees Fahrenheit) and add calcium chloride & calcium sulfate. Then begin milling the malted barley; unless you plan on malting the barley yourself, it usually can be bought in large bags that have already been malted. Once the barley goes through the miller, it is deposited into the hot water and continuously mixed until all the barley is put in. Mixing ensures that no dough balls will form and everything is distributed uniformly. Then we vorlauf, which is a weird german word for clarifying the wort that is being drawn out of the mash tun.

Next the wort (pre-fermentation sugar water) is transfered to the kettle where it is boiled to kill all organisms. Some hops are added during whirlpool, as well as, an additive that bonds to proteins so they can be removed. Eventually the wort is transfered to the fermenter where more hops or other ingredients will be added in. Then it is inoculated with yeast.

Cleaning is an important part of the brewing process, whether it be scraping the leftover grains out of the mash tun or sanitizing the kettle after use.

As fermentation occurs over time, various taste tests and gravity evaluations are performed. Plato and tank temperature are recorded on the designated clipboard.

The hops also need to get recirculated during the fermentation and many taste tests are performed. Once the beer is ready to go, it is transferred to the brightening tanks and the yeast is cropped. Once the beer is clear and bright, CO2 is added to carbonate the beer.

From this point the beer can be put into kegs or bottled using the bottling machine.