The coffee business is astonishing in its scope. The market for raw beans is expanding to accommodate newfound interest in high quality specialty coffees; small(er) batch Arabica lots which were once only a very small portion of beans traded globally are now as easy to find in retail as Starbucks brand beans. However, this market remains mostly dominated by larger corporations and, as with other commodity crops, there are literal and figurative distances between those who produce coffee and those who consume the finished product. Permaculture once more could be the key to remedying this. Already cooperatives around the world are making attempts to integrate coffee into biodiverse environments. The coffee market itself is already saturated with certified organic coffees and with consumers who seek these certifications eagerly. By shifting the focus of coffee to the taste of place, growers could potentially create a high demand for coffees grown in permaculture environments. A clean, well-cared for permaculture system would undoubtedly be able to produce quality coffee, and what better taste of place to boast of? The push towards sustainability in the present coffee industry creates opportunities for permaculture to shine and permaculture as a design system would benefit the industry immensely.

Culture of Coffee

After the introduction of coffee, its popularity was inevitable. The drink made its way into people’s hands around the world, becoming a staple along side tea, wine, and beer. Coffee was popularized by wealthy consumers, and due to its exotic nature and high cost, it became a status symbol. Booming coffee farming and vastly underpaid workers brought prices down, and the hot drink became widely available to the general public. For many people, coffee is a staple of everyday life. It’s affordable, readily accessible, and easy to make. It hasn’t always been that way, though, and the culture surrounding coffee continues to evolve. Its first documented use in Turkey was as a medical substance to treat stomach issues (Cowan 17). Now, it is often used as a socializing medium; the popularity of cafes has skyrocketed since their inception in the 16th century (Jolliffe 8). Some are now looking for the most luxurious ways to drink their morning pick-me-up, whether it’s having a barista create latte art, ordering it to be brewed by-the-cup, or buying incredibly extravagant drinks. Others look at the beverage as a mandatory drink to chug on their way to work or school, taking a more utilitarian view. Coffee has become wildly popular around the world, and the industry shows no signs of slowing down.

Cafés Create an Intellectual Stew

Photo by Annie. Words by Bach.

You can thank coffee for electricity, existentialism, the FDA, the Enlightenment, and Beethoven’s 5th. That may be a stretch, but Benjamin Franklin, Søren Kierkegaard, Teddy Roosevelt, Voltaire and Beethoven are just a few of the noted thinkers who drank inordinate amounts of coffee. Bach wrote The Coffee Cantata in 1732 to defend the Vienna coffeehouse scene (Pendergrast 1999:11), Maragaret Atwood helped create a coffee with The Smithsonian and coffee allegedly killed Balzac.

Mark Pendergrast, the author of Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How it Transformed Our World points out “One of the ironies about coffee is it makes people think. It sort of creates egalitarian places—coffeehouses where people can come together—and so the French Revolution and the American Revolution were planned in coffeehouses” while being interviewed on NPR’s “Morning Edition.” In his book he writes that the cafés “provided an intellectual stew” and allowed men and women to exchange ideas without impropriety (9). In Uncommon Grounds and during the interview he asserts that cafés made a major impact on the rise of business, progressed literature and newspapers and sobered up Western Civilization.

I believe the superfluous amount of coffee shops today may be in response to our vanishing sense of community and time for free thought in the digital age. I love Jay Oldenburg’s piece “Our Vanishing “Third Places.” One of his many valid arguments is that “Third places are ‘sorting’ areas. While third places serve to promote the habit of association generally, they are also the places in which those with special interests find one another. In third places, amateur musicians, shooting enthusiasts, poetry lovers, fishermen, scuba divers, etc., get introduced and find local outlets for their interests. Here is provided the basis of whatever kind and degree of local culture will emerge. In the modern subdivision, “local” culture is provided by television.” (Oldenberg 1996)

I often think about his argument for the balancing “third place” (home and work being an imbalanced bipod) when opening my screen at a coffee shop. And while I think it is important to engage with other humans or the occasional piece of paper while working at a coffee shop, I also believe coffee shops provide a supervisory relationship for academics and artists. Coffee shops provide an audience to be productive for and a reminder of the world outside of your house and work that is worth producing for.

Plus, coffee offers hedonic and utilitarian motivation!

An ideal coffee production system created using a permacultural design lens

By Thomas Schoch [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

In order for coffee to be a sustainable crop it must be grown in a food forest environment because it has been shown that shade grown coffee helps to foster a stronger local ecosystem than monocrop coffee and it also may help farmers adapt to climate change faster. (Souza et al. 2011, 179)

Among the benefits of a coffee based agroforestry system is “greater mycorrhizal incidence at deeper soil layers” which means that phosphorous in the soil would be much more readily available to the coffea plants than in a monocrop food system. (Cardoso et al. 2003, 33)

I also think that the coffee roaster should buy all the coffee beans from a single coffee producer rather than skim just the best beans off the top. I think that refusing to buy anything but the best puts an unfair burden on the farmers who are typically in a very low economic class. It would be preferable for a roaster to promise to buy all the beans from a farm and work with the farmers to produce the best possible coffee beans.

Geology, Soils, and Coffee

Photo: Coffee plantation, Kauaʻi, Hawaii (Wikimedia)

Coffee trees must be grown at certain elevations, with Robusta typically at 800m and below and Arabica at higher elevations, in certain countries up to over 2,000m. The best coffee is grown in deep, well-draining sandy loam or volcanic red earth with a slightly acidic pH of 5.3-6.0. Heavy clay, loam, or sand is unsuitable because of poor aeration, or because the soil will dry rapidly. Erosion can also be an issue. (Assefa et al.; Bullough)

Coffee tree in Rwanda by Colleen Taugher

Much of the world’s coffee is grown in areas where tectonic activity has formed mountains and mountain ranges or chains, including the extinct Mount Kenya in Africa, the active Apaneca-Ilamatepec range in El Salvador, the Andes in South America, and even the islands of Hawaii. (Hoffmann) Along with the tropical climates and high altitudes coffee needs to grow, these mountains provide fertile, nutrient rich soils the coffee trees can thrive in called Andisols. Formed in volcanic ash, these soils can include elements such as phosphorus, nitrogen, potassium, calcium, zinc and boron which are all used by the plant to help it produce coffee. (Bullough)

Izalco, an active volcano located in Western El Salvador. by Angela Rucker, USAID

Even though coffee trees are growing in young, fertile volcanic soils, intense coffee production continues to deplete nutrients, leading certain farmers to use chemical fertilizers as well as herbicides and pesticides. Many of these are not only bad for the environment but may also further deplete soils of what the trees really need. (Cerdán et al.) Another issue faced by farmers is the danger of the proximity of farms to active volcanoes – a huge risk in order to grow in some of the best suited soils for achieving great coffee quality. (Hoffmann)

Coffee and Natural History

Photo: Coffee and banana agroforestry in Uganda by James Anderson, World Resources Institute.

While over 120 different species of coffee trees (coffea) have been identified, the two most commonly used in the production of coffee are Arabica (Coffea arabica) and Robusta (Coffea canephora). Robusta is more resistant to disease, grown at lower altitudes, warmer temperatures, and produces higher yields; however, it generally makes coffee of lesser quality. (Hoffmann) The majority of coffee produced uses Arabica which originated in Ethiopia and is grown at higher altitudes. It gained popularity as a drink in Yemen around 1500 and has spread throughout the world since, mainly due to trade and colonization. (Topik) Coffee is grown in tropical climates between the Tropic of Capricorn and Tropic of Cancer in Africa, Asia, Central, and South America.

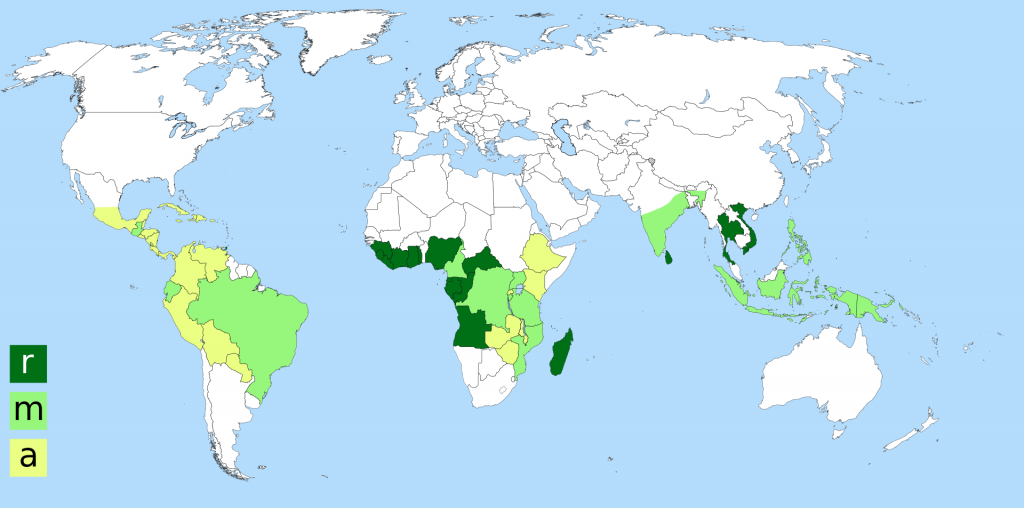

This map shows areas of coffee cultivation by type of coffee:

r: Robusta

m: Both Robusta and Arabica

a: Arabica

(Wikimedia)

Coffee trees can grow up to 8 meters high but are usually pruned to a shrub size more suitable for harvesting. (Kew) The fruit of the coffee tree is called a cherry, with two or sometimes one coffee seed, or bean growing inside. After a period of rain that allows trees to begin flowering, most trees then take up to 9 months for these cherries to ripen. Different varieties of Arabica include Bourbon, Pacamara, Typica, and SL-28 and the colors of ripe cherries can range from yellow to dark red-purple depending on the variety. (Hoffman)

Green Coffee – The beans that have been processed and are ready to be roasted. by Dan Bollinger

Coffee Flowers in Plantation of Brazil by Marcelo Corrêa

Ripe coffee berries of the mundo novo variety ready for harvesting. by Jonathan Wilkins

Coffee does well when grown as traditional in shade, well draining and nutrient rich soils (usually volcanic), and at altitudes of 950–2000+ m. Climate change and other effects such as diseases and pests -coffee leaf rust and the coffee cherry borer- threaten coffee production and quality. (Kew) Most trees are grown on small farms rather than large estates and there is increased effort in agroforestry, biodynamic farming, and farmer education to help produce healthier trees.