Natural History of Oysters (Part 2)

Left to their own devices, oysters grow in clusters upon one another, forming uneven beds. Their shells continue to grow in whatever direction they are able, resulting in irregular shapes and sizes. However, because of an ever-increasing market for both meat and raw oysters, aquaculture methods are implemented by oyster growers to produce more calculable results. During nursery propagation, oysters can be cultivated using either on- or off-bottom systems, depending on the variety and location (Chew, 68). Meat oysters, for example, are often grown in beds or mudflats, and may even be allowed to remain clustered together. Other varieties may be separated from one another and placed in mesh bags; these bags are suspended in the water column and allowed to rotate with the tides and currents. This method of “tumbling” the growing oysters gives them more uniform shape and size (Chew, 72). The oyster can be harvested throughout the year, though many growers would argue for specific seasons as ideal harvesting times. Typically, the oyster is more flavorful before spawning begins; up to the act itself one might detect a “spermy” flavor, and afterwards the taste become insipid (Jacobsen, 18). Similarly, in more seasonal climates, daily temperatures of the ambient water can begin to affect flavor.

There was once a time when 80% of the oyster market was for meats, intended to be cooked, with the remaining 20% reserved for oysters to be eaten raw. Presently, these figures can be reversed, with a solid 80% of cultivated oysters now being intended for the half-shell. Recent years have been tough on the oyster industry due to acidification and ever-growing pollution. Demand remains high however, and the industry is booming. Crassostrea gigas, the Pacific, is favorable for aquaculture because it is faster-growing than the delicate Crassostrea sikamea, the Kumamoto. The native Olympia, Ostrea lurida, was once harvested nearly to extinction, and has been restored to the bays and inlets of the PNW by careful cultivation (Jacobsen, 26). Comparatively, the Olympia and Pacifics are the more desirable oysters to grow from a retail perspective; they can be harvested after two or three years as opposed to five or more with the Kumamotos. The Kumamoto can snatch a higher price by weight or in the oyster bar, but is less sustainable for high production rates. As such, growers will often cultivate many beds or lines of Pacifics and Olympias, and devote some of their energy to tending to the Kumamotos. The final destination of the oyster varies depending on the grower, but C. sikamea, being more valuable and most likely intended to be consumed raw, is often tumbled in bags to produce the small, characteristic shells with more uniformity. A voracious C. gigas might be cultivated on an algae bed so that it can become fat and flavorful.

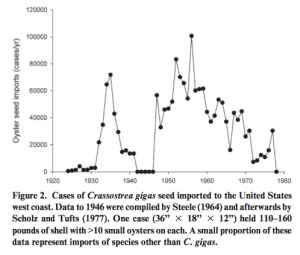

In recent years, seed from Japan have been imported to the West coast due to declines in native seed success (White, 47). This again can be attributed to the acidification and pollution the oceans are currently facing. Continued efforts are being put forth the keep populations sustained, with growers facing new challenge annually. Cultivation of oysters often comes with the threat of invasive species, and in the PNW, non-native oysters have been imported for centuries. Though regulations are now in place to prevent these invasive species from hitching a ride, many predators and parasites still pose a threat to the cultivate oyster populations. At one time, O. lurida was highly sought after and protected on aquaculture reserves (Bulseco, 65). With decline in its population due to over-harvesting, growers turned to C. gigas and other shellfish for further cultivation; presently these species are more favored on the reserves than they once were.

The oyster is an intoxicant of a kind, and it has captivated the food world for decades already. With terroir on the rise in food marketing, the oyster is an ideal product. The current market is mainly seeking raw oysters (the better to exemplify their taste of place) and growers have to keep up with the increasing popularity.