- Meet and greet at Mission Creek Park

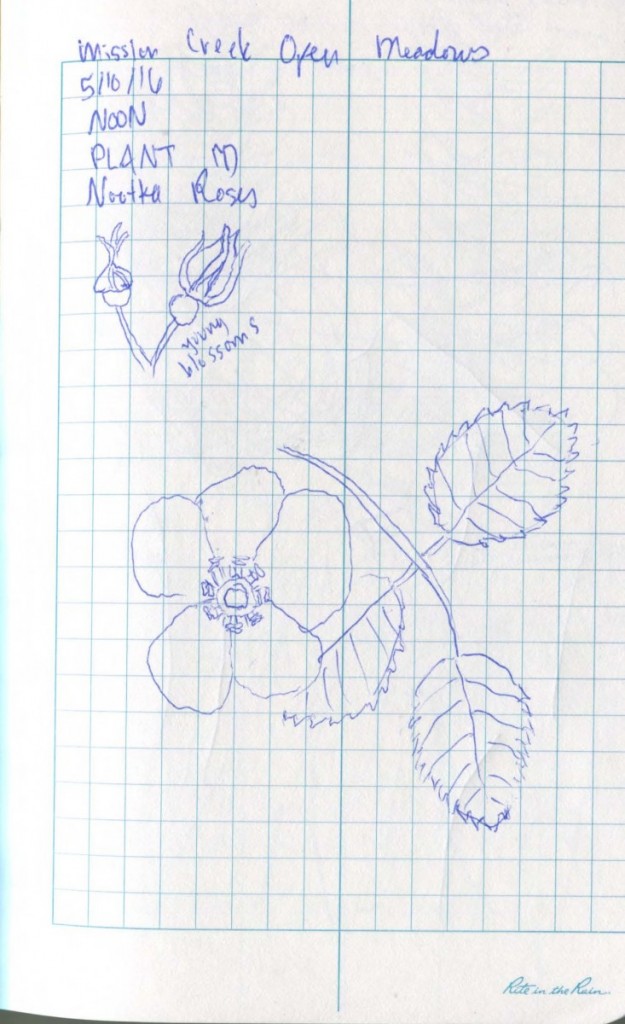

- Nootka Roses blooming.

- Maple Cathedral at Mission Creek Park.

- Mission Creek Meadow. Human for Scale.

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Riparian Area

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Estuary

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Riparian Overlook

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Marsh Plants

- Priest Point Park Ellis Cove

- Priest Point Park Old Growth Forest

- Slime Molds at Priest Point Park

- Slime Molds at Priest Point Park

Overview

During week 7, the Sassy Dolphins team, consisting of Maina, Taren, and Frances, visited six sites in the Olympia area to conduct field research and speculate possible changes to the ecology and landscape as global sea levels rise due to climate change. We did not have a team plan but had many conversations out loud about possible outcomes and the logic of different ecologies.

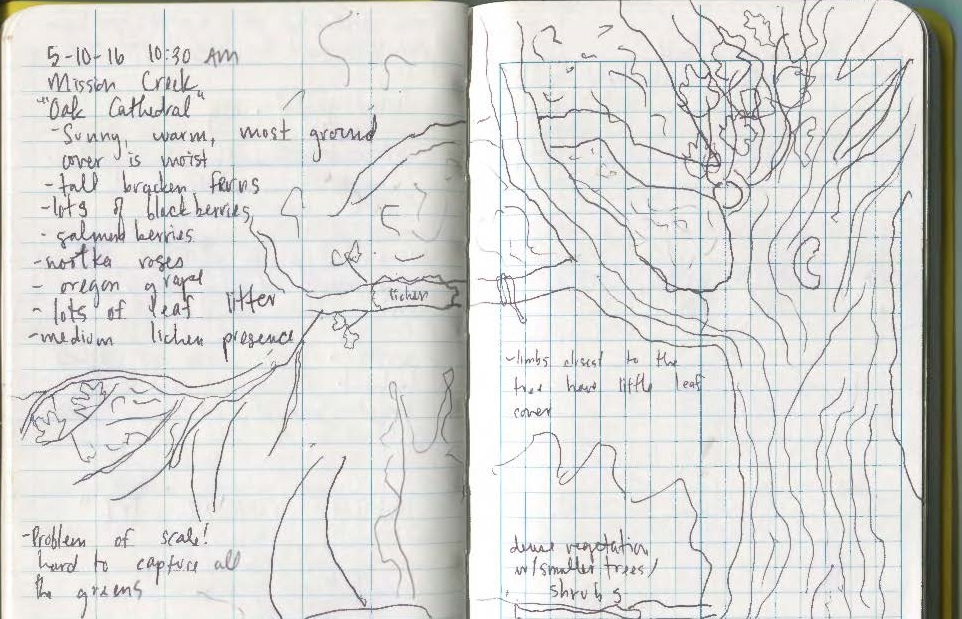

Site 1: Mission Creek Maple Cathedral

Contrary to my poor field notes, this was the Maple Cathedral, not the “Oak Cathedral.”

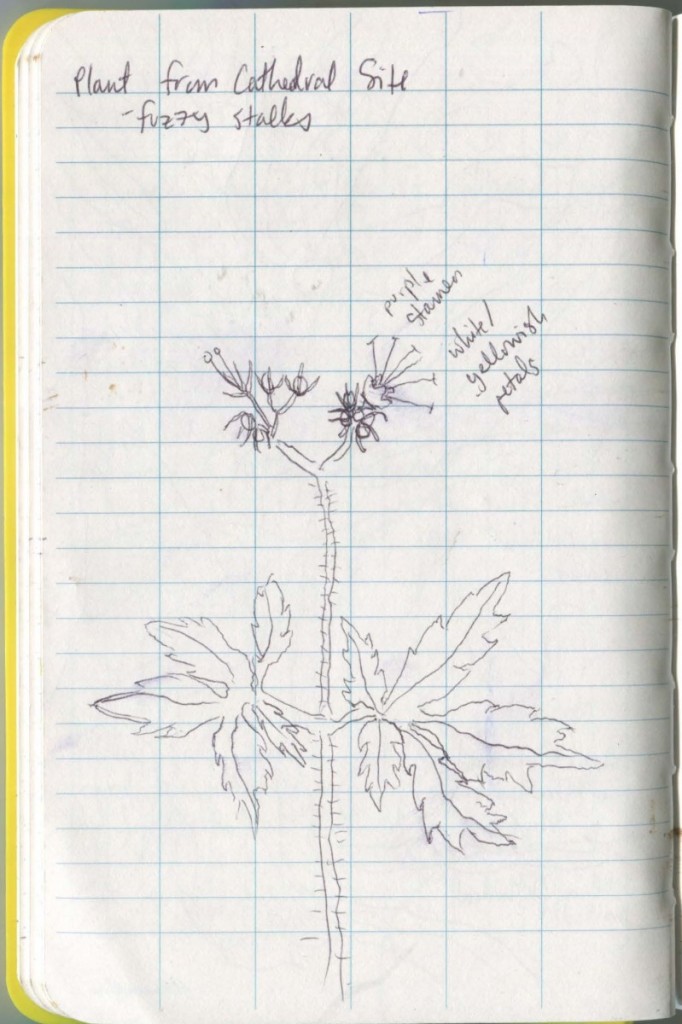

Pacific Waterleaf

It was hot and sunny on the day we visited Mission Creek Park. The creek itself was on the small side, but it is still considered an important tributary to South Puget Sound and helps to support salmon habitat.

The park seemed highly maintained by humans, as there was a lot of intentional landscaping at the beginning of the trail to the “Cathedral.” Most of the ground cover was moist despite the heat. There are many Bracken Ferns (most of which are almost as tall as our group members, if not taller), black, thimble and salmon berry bushes. Included in the ample leaf litter is Oregon Grape, Pacific Waterleaf, Three Leaved Anemones, and Creeping Buttercup. There was a moderate amount of lichen, but nothing compared to the coast. Most of the plants are common in moist and shady sites, and there is evidence that periodically there is water held in parts of the site that look like dry creek beds; my contention is that it floods often with regular rainfall.

We tried a short cut to the meadow through some tall reeds and wound up in soggy, flooded mud, perhaps evidence of some of the aforementioned flooding that was previously hidden from view.

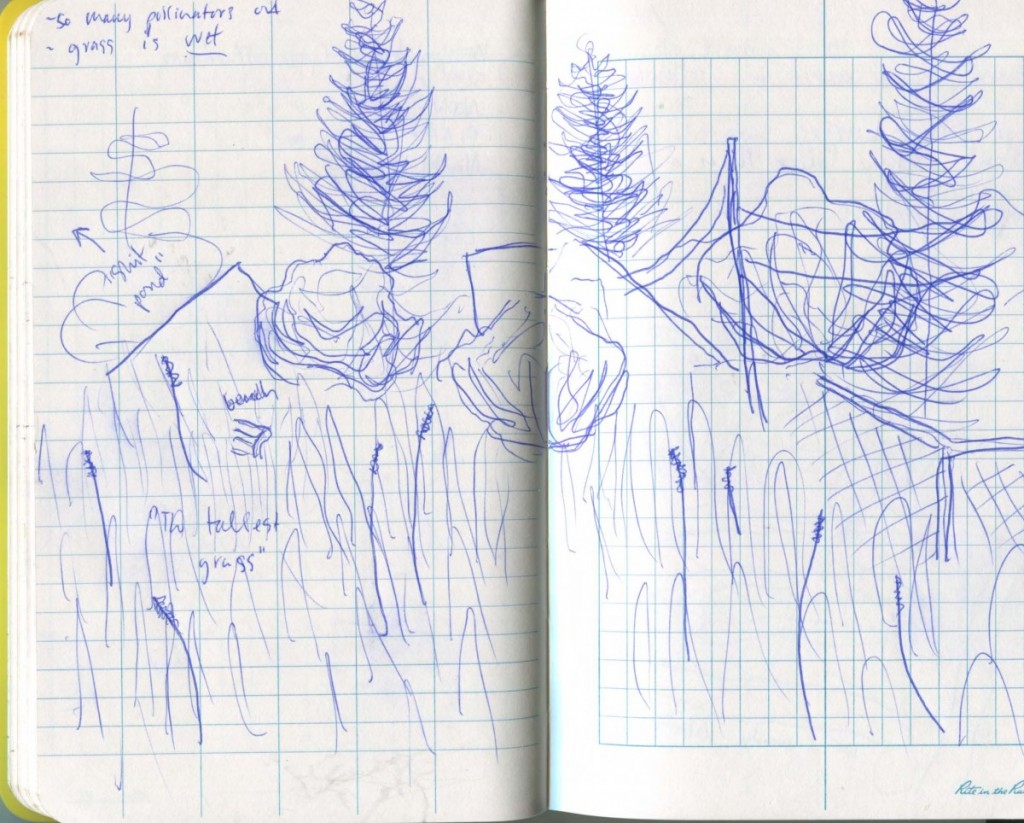

Site 2: Mission Park Creek Meadow

There was a very well maintained trail running through multiple kinds of tall grass species and several “carousels” of taller trees. There were Nootka Roses hidden under trees and some Lupines next to the trail. The trail to the meadow felt as though it dropped down, and the tree concentrations are at a substantively lower elevation than the majority of the grass areas.

According to the National Park Service, meadows are critical habitats as they provide a natural water reservoir to both prevent flooding and “delay the timing of spring run off,” which is useful during dry seasons (“Meadow Functions”). They also play a part in water purification, as plants and roots absorb nitrogen and other nutrients from the ground water before it heads to larger bodies, like the Puget Sound.

I had questions about the impact of global warming on this site: if rain fall increases as sea levels rise and ocean temperatures increase, will that create more opportunities for meadows to filter water emptying into rivers and larger bodies of water, or will the intensity of the rain fall take vital mud and debris from the ecosystem?

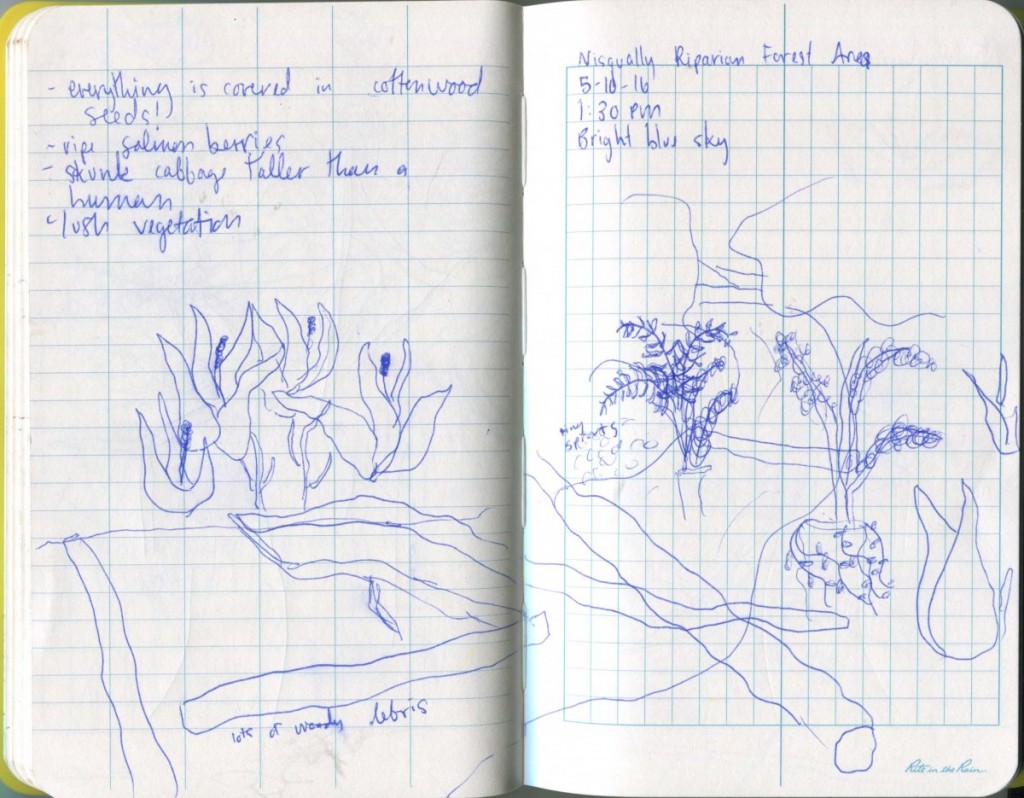

Site 3: Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Riparian Area

On the same day, we visited the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Estuary. It was still bright and warm outside.

We started on the Easterly part of the Twin Barns Loop Trail until we found the Riparian Overlook Forest Trail. Less than a minute into this walk we encountered a deer sprinting for its life and a small pod (sic) of rabbits.

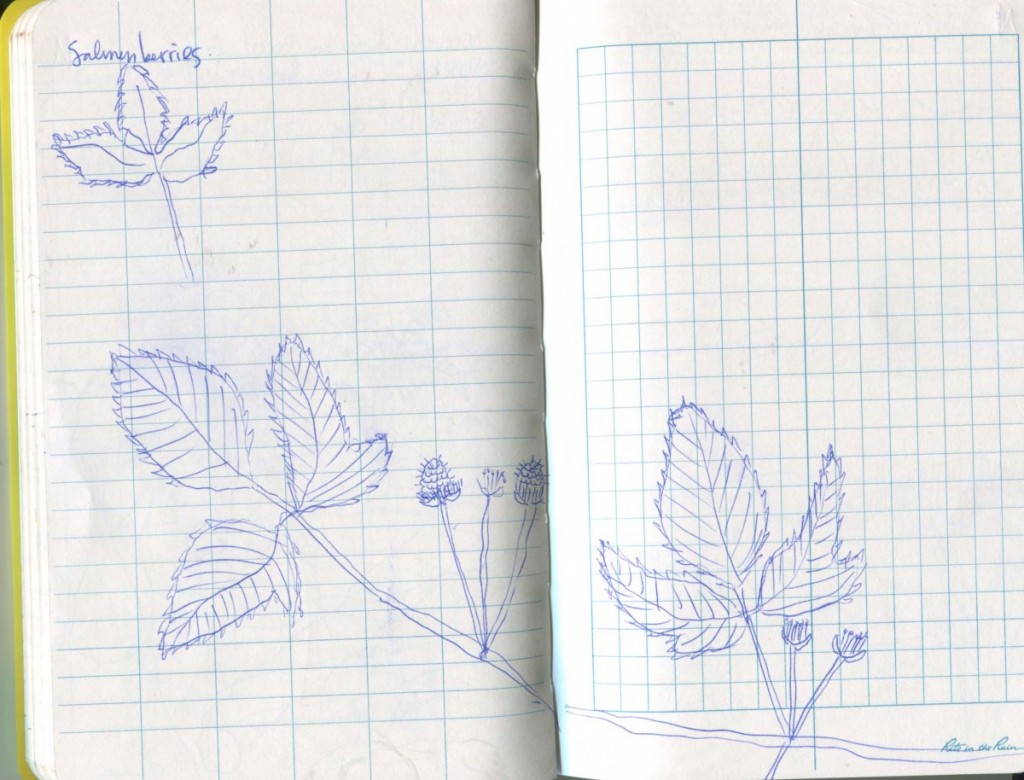

There were many salmonberry bushes on the brink of ripening. The sides of the boardwalk were covered with a white fuzzy cottonwood pollen, as were many of the bodies of water. We noticed that the vegetation was incredibly lush, and all of the various waterways were littered with lots of woody debris as well as skunk cabbage. This river is probably mostly comprised of snow melt traveling from Mount Rainier, combining forces with debris to provide a cool, calm and sheltered pathway for salmon and a living area for non-anadromous fish.

One could imagine that as the oceans rise, the salt water from the sea will have more opportunities to head further inland and up the Nisqually River and the smaller tributaries. This will dramatically alter the plant and animal life that is currently in the marshy, primarily fresh water habitat of the Riparian area.

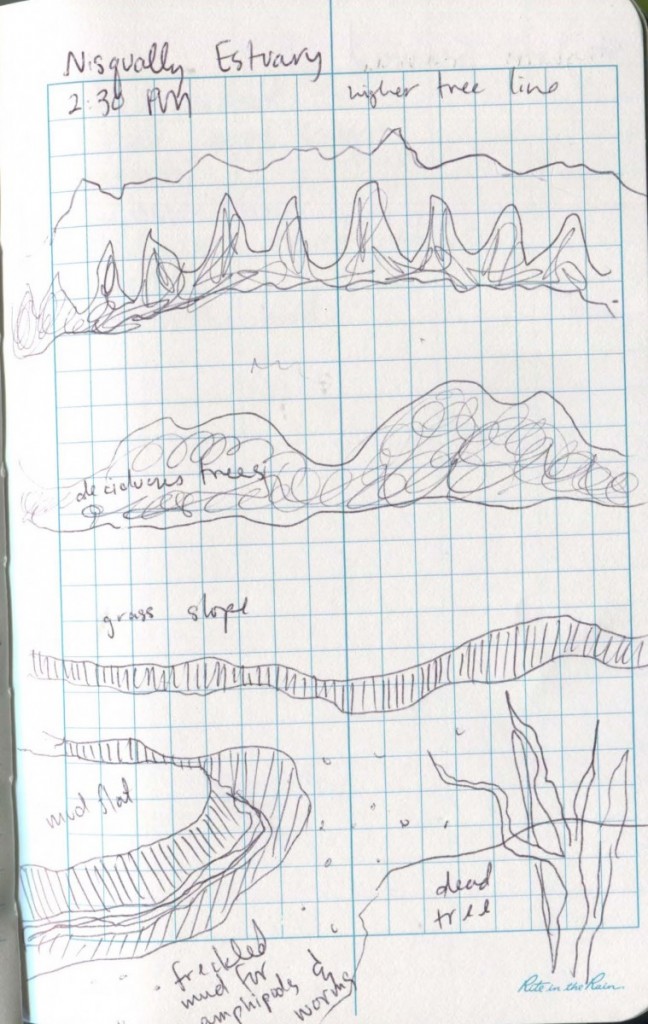

Site 4: Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge Estuary

We walked along the estuary trail, which served as a large visual boundary between the riparian area, the estuary, and the delta. Behind us sat the riparian area, to the left was the estuary, and to the right, the delta. My educated guess is that the delta could be likened to a “ria coast,” which is a “deeply embayed coast resulting from submergence of a landmass dissected by streams.” Much of this area was also likely carved by mud flow, or specifically “soil creep,” which would be a good title for a heavy metal band. Soil creep is the shallow earth flow “affecting only the soil and regolith, [and] are common on sod-covered and forested slopes that have been saturated by heavy rains.” This is a form of mass wasting, which specifically occurs on slops and happens when the internal strength of a structure declines so that the force of gravity cannot be restricted.

As far as wildlife, to notice that you are in a bird sanctuary is inescapable. In the estuary, many Canadian Geese rested or lumbered between the taller grasses. Two Blue Herons and a smaller assortment of ducks and gulls fed in the ribbons of rivers in the delta, shaped by the structure of bedrock beneath the clay. Many barn swallows darted between pedestrians. The estuary was littered with common and tufted vetch, which are nitrogen fixers. These help filter fresh water on its way out to sea.

Upon closer inspection, small pockmarks began to appear in the drying sediment of the delta. This is where crustaceans, worms, shrimp, and smaller amphipods hid during the low-tide to retain moisture and seek solace from predators.

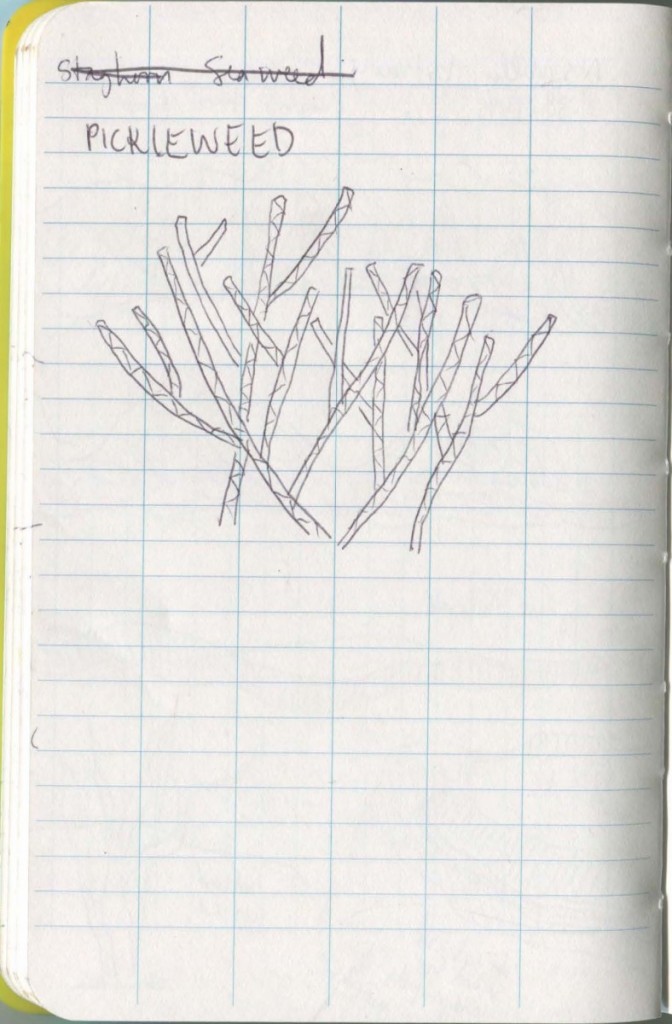

The “grass” was in fact the salt water marsh plant pickleweed (Salicornia sp.) covered with layers of dehydrated seaweeds.

There was no available rocky substrate, but a few man made structures such as sand bag walls and the wood from the boardwalk were covered in colonies of California Blue Mussels and Acorn Barnacles.

The dead snags appeared to be trees leftover from the farming history of the area; when the dike came down and the salt water was allowed to swell into the delta, they died but remain standing.

Deciduous trees outlined the boundary of the delta and served as reminders of the limits of the salt water. Many small mounds, which could be compared to tinier, mud sea stacks, sat alone, indicating that layers of mud have been removed over time from the movement of water.

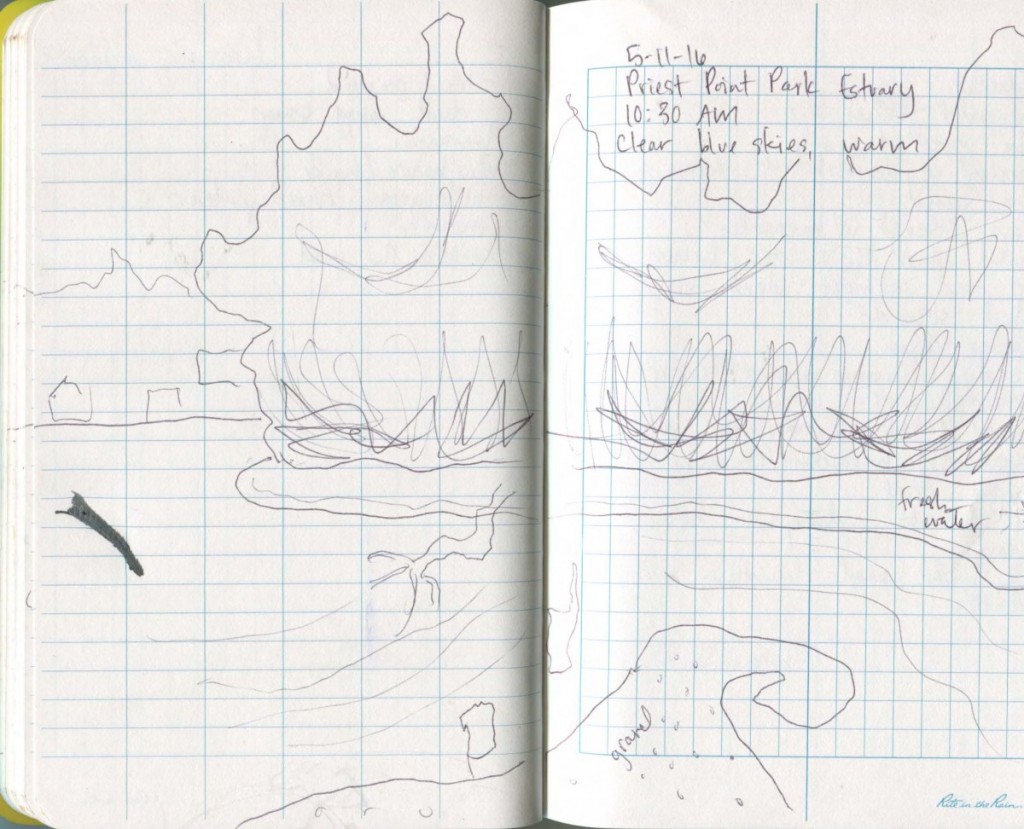

Site 5: Priest Point Park Estuary

Priest Point Park is named after a group of white Missionaries who came to Puget Sound in 1848 to convert local tribes to Christianity; specifically, the Squaxin, Nisqually, Puyallup, and Snoqualmie. They operated a boarding house on site, and chose the “convenience” of this location due to its relative position to a tribal village (“Priest Point Park”).

The Priest Point Park Estuary is fed by Ellis Creek. The shoreline is covered in marsh plants and seaweeds, very similar to BJFJ Nisqually Wildlife Refuge. There is a tiny spit on the southeast portion of the beach. One can hear many people, construction from across the Sound, the slow hiss of barnacles, and the scream of a mother duck protecting her babies from two Bald Eagles diving after them. Of the three, this site has the most non-human noise. There were many tiny crabs hiding in the holes provided by the roots of marsh plants, mud-skippers floating in the mellow Puget Sound water lapping at the shore, and too many crows cawing while picking at exposed bivalves and mussels.

According to “Streamside Livin,'” the road culverts on East Bay Drive NE provide a substantive limit to access to Ellis Creek for adult coho and chum, so the woody debris lining the stream side may not provide enough of an opportunity for salmon to access their natal streams. The salt water plant life extends for at least 30 yards and ends abruptly at the high tide mark, where the forested area of the park begins.

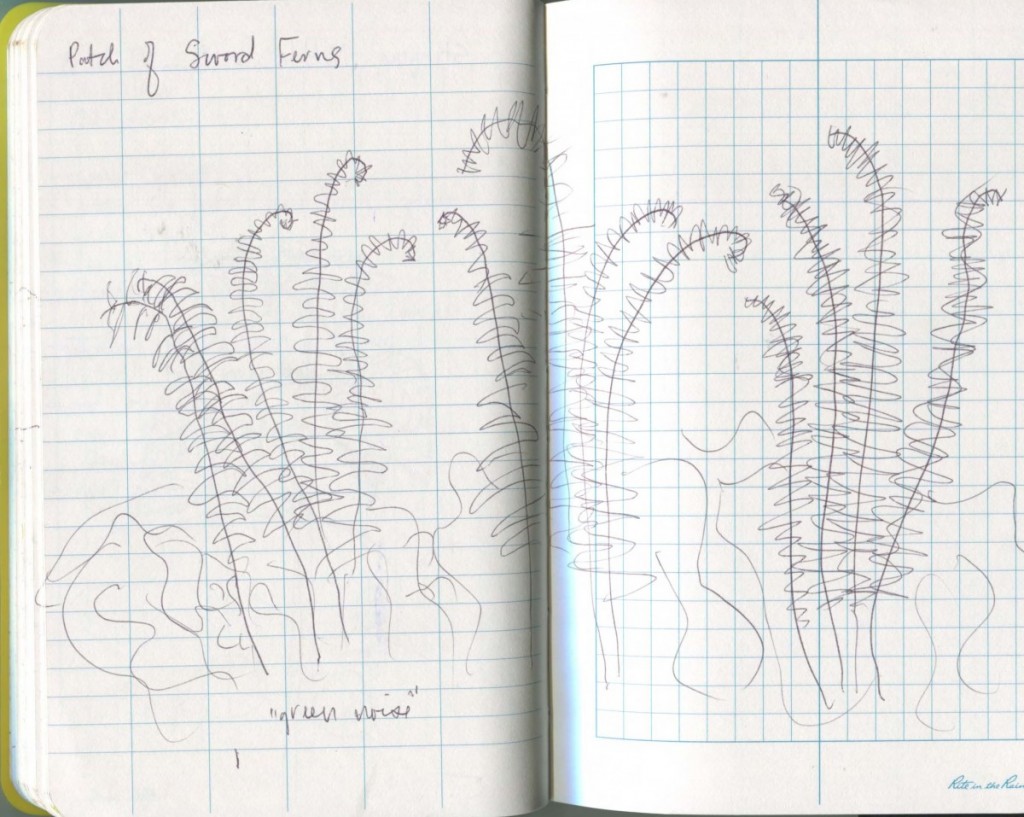

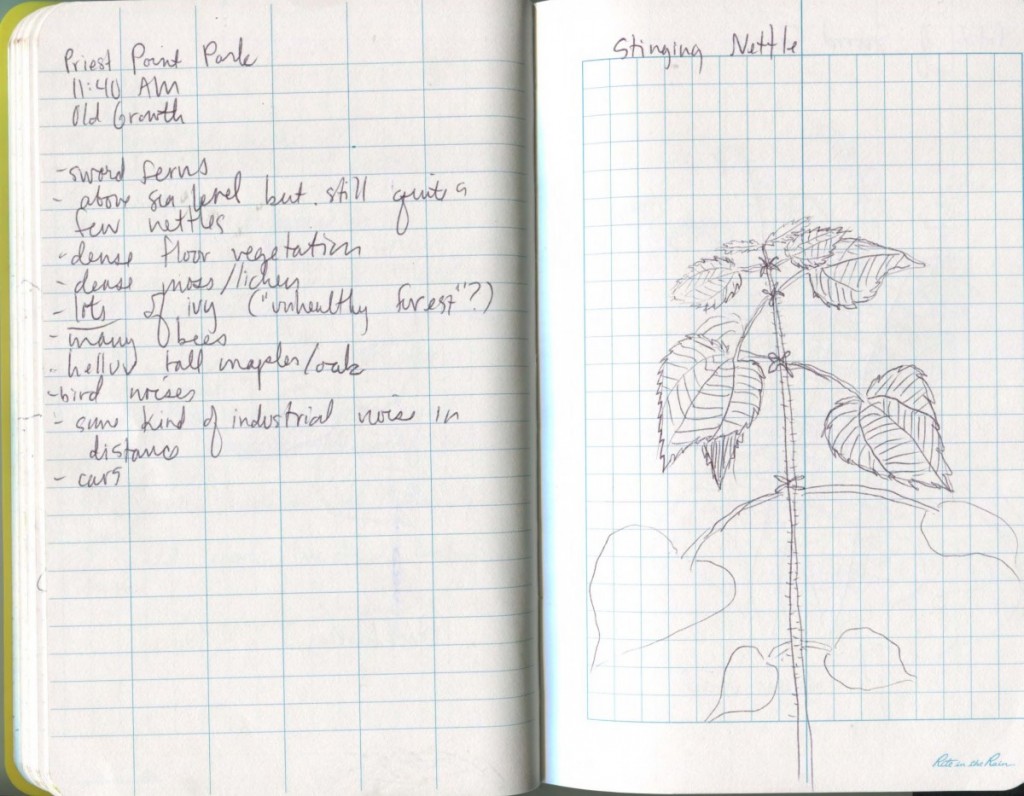

Site 6: Priest Point Park Old Growth

The cadence of industrial and bird noises in the old growth section of the park seem to equally match each other.

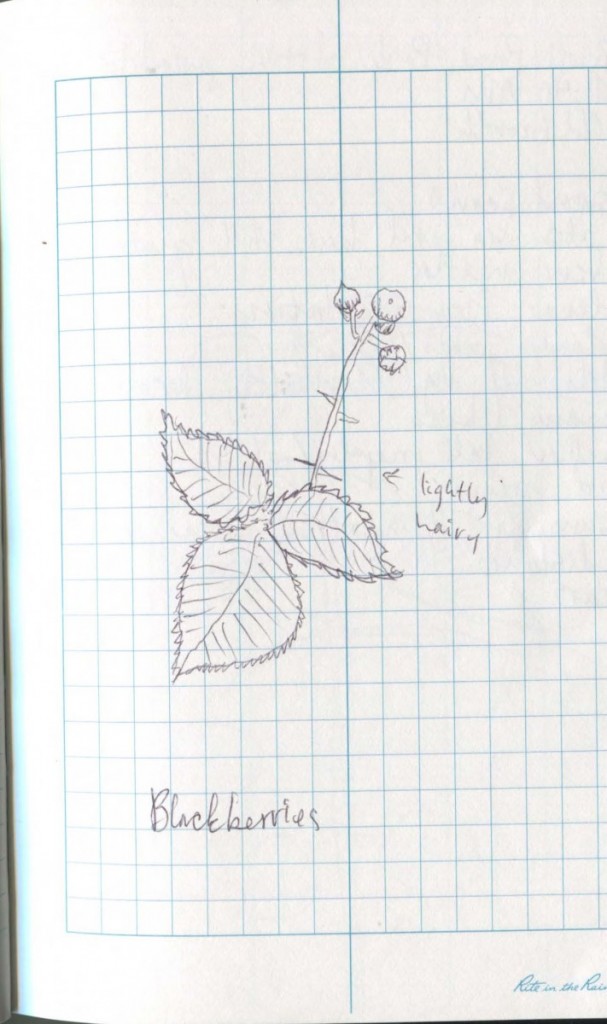

There is noticeable “green noise,” as the forest floor is covered with dense vegetation, including tons of Sword Fern and Stinging Nettles, who like the moist soil. There is also a lot of climbing ivy as well as various moss and lichen species. Also included are: Piggyback Plant, Broad-leaved Starflower, Western Trilium, False Solomon’s-Seal, Indian-plum, and Orange Trumpet Honeysuckle. There are many tree stumps in various stages of decomposition, including one covered in at least four species of slime mold. Slime molds are decomposers and were once considered fungi; as single-celled organisms, they “fruit,” like in the photos, when their food source is running out and they must combine forces to locate another (!!!!!!!!).

When I think about sea-level rise and how it might impact this part of the park, I don’t feel the anxiety I do at sea level. This part of the park feels elevated above the danger. In an attempt to play the game, “What If,” I think about whether a Washaway Beach type of situation may impact the cliff sides, but the water is too calm as the Puget Sound is not subject to the same violent wave action as the coast.

Works Cited

Meadow Functions. National Park Service. Web. 27 May 2016.

Priest Point Park. City of Olympia. Web. 27 May 2016.

Streamside Livin’. Thurston County Storm and Surface Water. Web. 27 May 2016.