This quarter our group explored the importance of lichen restoration for the ecosystem and our community. While on this adventure, we made many discoveries and are hopeful for the future of restoration. It may be a long road but for us and other passionate lichenologists, there is hope. Through research, experimentation and community outreach, we intend to make progress for future scientific advancements.

Lichens play an integral part in the prairie community. They retain moisture and increase the boundary layer, provide habitat for invertebrates, nesting material for birds, and are a food source for multiple animals. Trevor Goward maintains that lichens are the glue that holds the bunchgrass community together. While most prairie restoration efforts are for native plants and organisms such as the Taylor’s Checkerspot that depend on this bunchgrass community, looking at the lichen is an important step in overall prairie restoration.

Many studies have been conducted on lichen restoration, although few have been conducted in Washington or looking at fire restoration. However, we can take pieces of research from around the world to put together a lichen restoration plan for specific sites in Washington such as the Mima Mounds.

Possible courses of action:

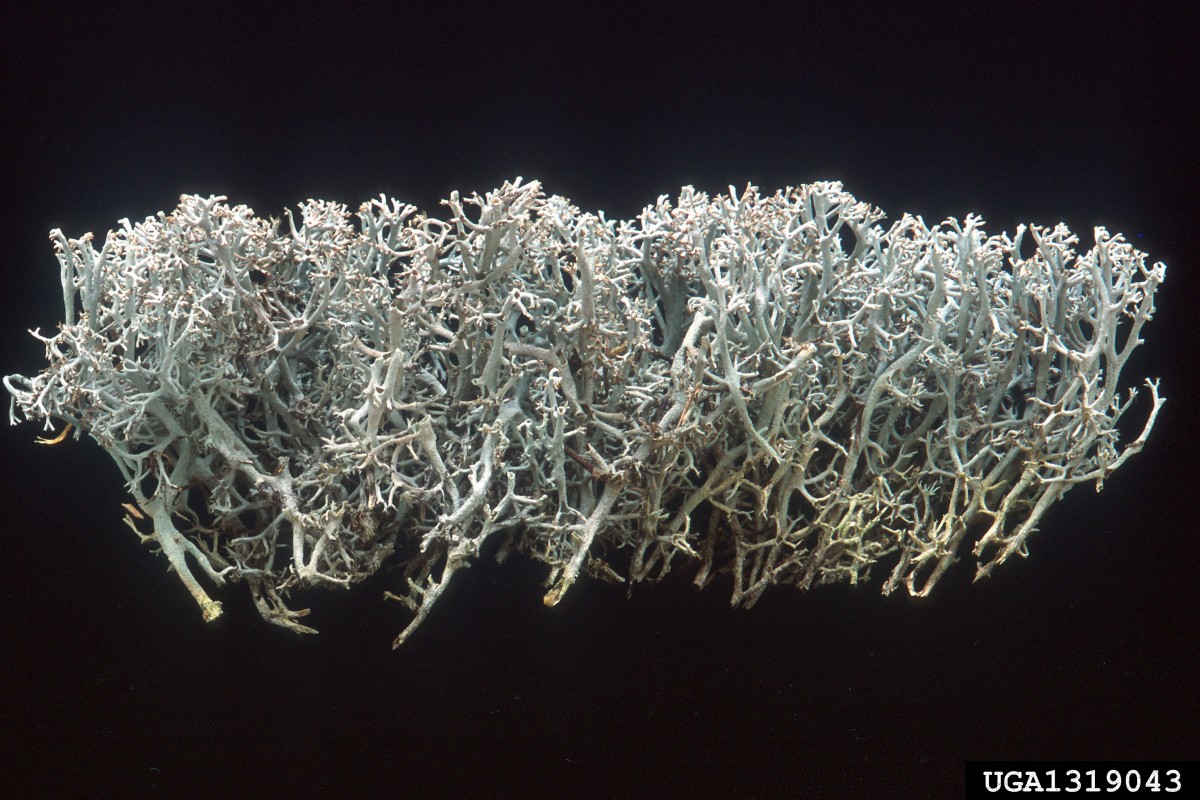

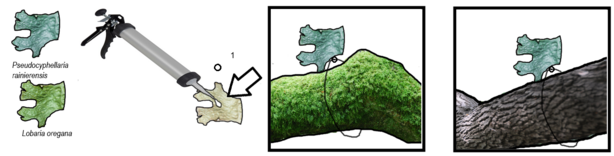

Lichen fragmentation: Reindeer lichens are used to being grazed and trampled by reindeer. When the lichens are not overgrazed, the reindeer nibbles and tramples can actually increase the lichen mat size because of fragmentation. Each little piece of lichen has the ability to grow a whole new plant, genetically identical to the parent plant. Different methods of fragmentation have been tried, from leaf blowers to mimicking reindeer trampling. This is a possible course of action at the Mima Mounds to increase/restore lichen populations after burning.

One experiment that we plan to implement in the prairies is to test the pH of the soil. The soil that would be tested is burned and unburned plots, and also looking at locations where lichens are high in population.

Photo from http://www.soil-net.com/album/Equipment/pH%20testing/slides/Soil%20pH%20testing%2010.html

This is important in the prairies because it is known that change in the pH of substrates can change the lichen growth. The study will be performed by making a slurry of multiple soil samples, and then testing them. Over a period of time, the same areas would be tested again and observations would be made about species of lichen in the area. An experiment like this, is a stepping stone in a great understanding of prairie lichens.

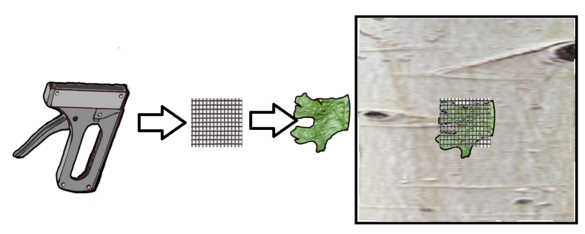

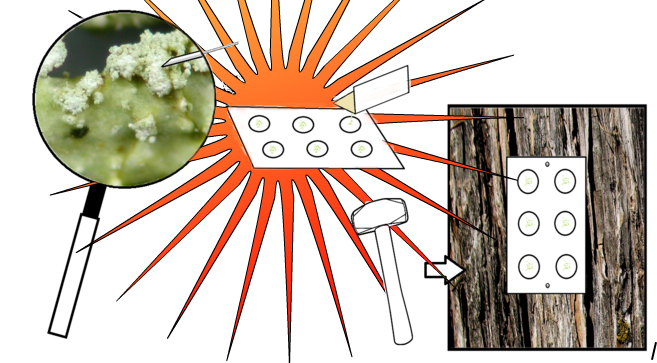

During this quarter our group decided to perform an experiment with growing lichens from Formula 29. We used milk, flour, yeast, spirulina, fertilizer and jello, then boiled them over a stove. Then lichen thallus was added and we were able to paint this mixture onto substrates (tree bark) in a wooded area.

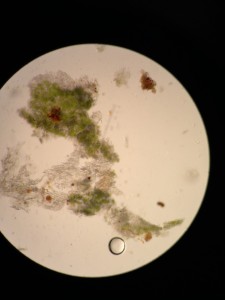

After 7 weeks, growth was found and we took a scrapping. Under the microscope algae was found. This method could be attempted in the prairies, and we could try to grow certain reindeer lichens in the burned areas.

Lichen Awareness:

We are going to design and implement various research and restoration projects that are fun and engaging to the public. There are no opportunities for the public to get engaged with lichen restoration currently, but things such as a lichen fragmentation scattering day or lichen formula painting parties could easily be arranged. In addition Evergreen students could lead field walks giving communities the ability to recognize what is in their own backyards, as well as highlighting the importance of classes that teach lichen taxonomy and ecology.

Community outreach is an important part of getting people to care about and understand lichens. Going into classrooms, retirement homes, or setting up booths at prairie appreciation day will bring lichen awareness to people of all ages. Connecting awareness to action by going into the field and surveying or dispersing lichen is informative and fun for children and adults, as well as helpful for lichen restoration. Follow-up monitoring of the lichen dispersal can be coordinated with interested parties.

Some alternate ideas we’ve come up with to make lichens more exciting:

- Lichen fashion line utilizing lichens both for dye and the thalli themselves as garments.

- Days of Our Lichens syndicated daytime drama; One Lichen to Live

- GMO supreme lichen master race -> human symbiosis

- Lichen comic books/coloring books

- Songs about lichen

Works Cited

Goward, T. 1991. The Enlichenment: Lichens and the Vanished Grasslands. B.C. Naturalist (29) 6; 8-9.

n and Nature Network

n and Nature Network mps, and community. The fact that we as Evergreen students have the opportunity to take a class about lichens and bryophytes is actually a privilege and a rarity. Much like the symbiosis of a lichen it would be mutually beneficial for us as students to lead walks throughout our community educating everyone about the wonders in our own backyards. The community would learn to sight-identify important species and students would reinforce their knowledge by teaching others. According to John Nestojko, a researcher in psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, “When compared to learners expecting a test, learners expecting to teach recalled more material correctly, they organized their recall more effectively and they had better memory for especially important information.” In the words of the ever inspiring rapper Rampage, it’s time to take it to the streets.

mps, and community. The fact that we as Evergreen students have the opportunity to take a class about lichens and bryophytes is actually a privilege and a rarity. Much like the symbiosis of a lichen it would be mutually beneficial for us as students to lead walks throughout our community educating everyone about the wonders in our own backyards. The community would learn to sight-identify important species and students would reinforce their knowledge by teaching others. According to John Nestojko, a researcher in psychology at Washington University in St. Louis, “When compared to learners expecting a test, learners expecting to teach recalled more material correctly, they organized their recall more effectively and they had better memory for especially important information.” In the words of the ever inspiring rapper Rampage, it’s time to take it to the streets. mpted to make our own lichen paint based off of

mpted to make our own lichen paint based off of

Recent Comments