What follows is a cocktail of tall tales and imaginings, peppered with pictures of lichen transplant methods as interpreted from scholarly lichenological articles.

Any lichness to real persons, events or experiments is not very likely.

1994: Willamette Valley. Bruce McCune, Stephen Sillett and pals collectively wonder, “How does forest succession affect epiphyte biomass?” Of course, they’re already aware that epiphyte biomass tends to be higher in older forest ecosystems.

“But how does that translate to lichen propagation via thallus fragments? What sort of niche is best for a developing thallus fragment?” The table buzzes.

Bruce McCune takes a long, slow swig of grog, his eyes downcast as the table squabbles.

“I think they favor an open environment. No No No, over exposure will destroy the developing thallus!” They fall silent as McCune’s gaze sweeps across the group. There’s an audible slurp as he finishes his tankard. He slams it on the table with one hand, while simultaneously flicking the froth from his beard with the other.

“We settle this…..” His eyes burn them. “With science.”

Thus, “Lichen Pendants for Transplant and Growth Experiments” was founded.

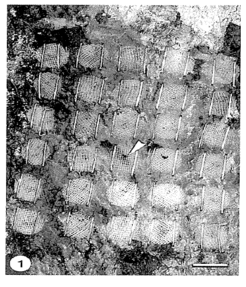

Fig. 1.

thallus pieces with at least two young lobes are collected, cleaned and attached to loops of nylon monofilament with silicone (1).

- Branch sections were selected, both with and without moss, in young and old-growth forest avoiding heavily shaded branches. (A rack was built to serve as substrate in the clearcuts.)

- Moss removed in old growth and added to moss-positive treatments in young forest and clearcut sites

- Lichen thalli were attached to the rack (clearcuts) or branch (forest) with 3mm nylon cord

Findings

Sillett and McCune found that cyanolichen transplants Lobaria oregana and Pseudocyphellaria rainierensis grew better in young and old-growth forests (20-30% increase in mass) than in clear cuts (<10%). Clear cuts also had much higher mortality rates (50-90%). Pseudocyphellaria rainierensis thalli grew 30% better when transplanted on moss than on bare bark, but after one year 25% more thalli were healthy on bark than moss. This may mean that moss is good for initial transplant– possibly for support and/or moisture retention– but may be detrimental to long-term health– possibly due to competition.

Meanwhile….East-central Sweden: Top-secret Headquarters of De Dåliga Åsnor för Träd–

The Arch-mage Lena Gustafsson, Knight of Fedrowitz and Princemeistress Hazell strategize about how to convince a power-mad tribe of ogres to leave a few trees when logging an entire forest.

These ogres are fierce, but not evil– just ignorant. De Dåliga Åsnor decide to develop an experiment that will illustrate to the ogres the value of remnant trees. It’s common knowledge in Sweden, that ogres are easily swayed by scientifically backed tables and graphs.

“Oh we’ll give ‘em a graph…”

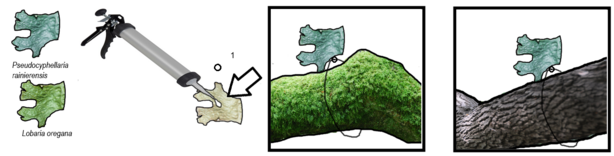

And so, De Dåliga Åsnor transplanted 1120 Lobaria pulmonaria thalli on 280 aspens at 35 sites incorporating clearcuts and remnant forest habitat.

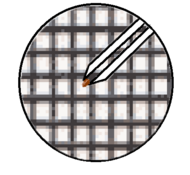

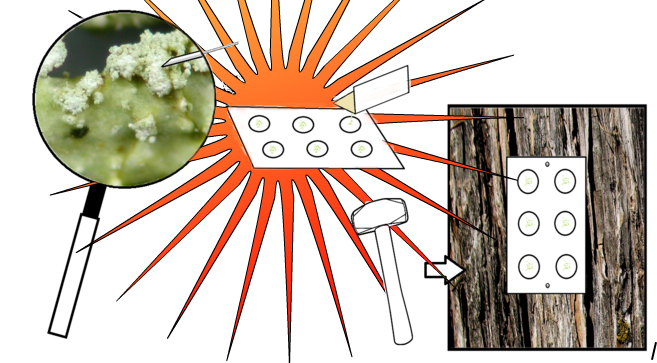

Fig. 2.

Lobaria pulmonaria thallus pieces are attached to north and south sides of aspen trunks using 6×6 cm plastic 1×1 cm mesh and staples.

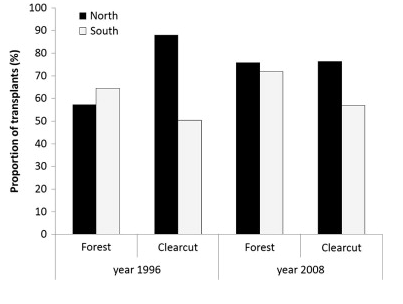

Fig. 3.

Proportion of transplants with ⩾50% vitality on north and south sides of trees, respectively, in clearcuts and forests, two and 14 years after transplantation. 22.3% survival after 14 years. (Gustafsson et al. 2013)

After two years, The logging ogres could not dispute the evidence clearly illustrated by the graph. Survival rates of transplanted thalli were clearly higher in north-exposed clearcuts. De Dåliga Åsnor continued to monitor the plots for another 12 years. Figure 3 is an updated graph illustrating survival rates at 2 and 14 years. The survival rates of northern exposed thalli would eventually even out, but the ogres’ appetite for scientific graphs had been satiated–the survival of the remnant trees ensured.

“But what about McCune and company? Their results showed higher mortality in clearcuts!”

McCune’s Lobaria oregana and Pseudocyphellaria rainierensis are more sensitive to air quality than Lena Gustafsson’s Lobaria pulmonaria. All of these are cyanolichens, which tend to prefer low pH, nitrogen poor environments like old-growth forests.

“What the hell does that mean,” you ask?

Lichens are poikilohydric, meaning they absorb moisture kinda like a sponge– soaking up pollutants from the atmosphere and leeched from rain, then drying out and concentrating these pollutants. The main culprits of loss of lichen biodiversity are presumed to be nitrogen (as NO and NO2, produced by combustion of fossil fuel and NH3, produced mostly by agriculture) and sulphur dioxide (largely from coal-burning power plants and large ocean vessels).

… … … …

The following is a top secret Swiss document regarding the propagation of lichen propagules.

I really shouldn’t be showing you this…

TOP SECRET Propagation of propagules TOP SECRET

1995. Swiss lichenologists.***REDACTED*** Top secret message!! Uh, yeah… so, they’re swiss. and uh, they wanna use propagules to start new lichens. They wanna plant ‘em in gauze to help them stick.

- Harvested vegetative propagules of Sticta sylvatica, Lobaria pulmonaria and Parmotrema crinitum with a wet paintbrush

- transferred to a petri dish of distilled water

- 8mm diameter surgical gauze discs stapled to tree trunk or moss mat

- apply propagules variously, depending on size

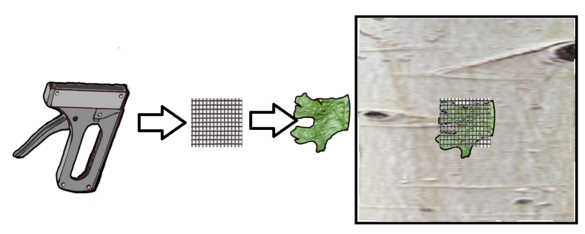

Fig. 4

Lichen propagules affixed to a tree trunk

(Frey et al. 1995)

Fig. 5

Frey et al. reported 1.3% survival of propagules in the first 6 months, but said this increased to 9% survival when propagules were placed carefully between the meshes

It’s a conspiracy, maaan!

It would seem that spawning a lichen from a propagule is not as easy as it sounds. Propagules take 2 months to attach to substrate and will likely fall out of mesh or gauze. The swiss experiment only noted lobule formation from propagules dispersed from transplanted adult thalli (after 30 months).

Japan, 2010: Yoshiaki Kon: a faculty member of Tokyo Metropolitan Hitotsubashi High School, and his long time friend, Yoshihito Ohmura: Department of Botany, National Museum of Nature and Science, are waaay into cutting edge lichenology. They go to all the conventions. Total fanboys. This year their project is gonna revolutionize the way we transplant lichens.

A mind-blowing game-changer.

Are you tired of your thallus sagging and your propagules fallin’ all out?

Have mesh and gauze left you with high mortality rates?

Has the slow nature of a lichen’s growth got you saying, “Dang these lichens, they’re so slow growing and they just won’t stick!”

We’ve all been there.

Don’t you wish there was a better way?

Well wish no more! YoshiCorp® has heard your prayers!!

- using sterile needle, scrape lichen soredia onto cartridge paper

- apply soredia to 7mm adhesive tape™ circles

- apply 6 tapes to a plastic plate

- apply plate to tree with stainless steel nails

It’s just that easy!*

*The adhesive tape method is more effective than gauze or mesh for propagule retention. Not all species will form thalli on adhesive**.

**YoshiCorp® are unsure why Ramalina yasudae doesn’t form thalli on adhesive, but they did have very limited success with R. yasudae using the mesh method, even though over half fell out.

Alright, kids, what’ve we learned?

Lichens need a firm anchor. Artificial methods of anchoring have high rates of failure. They also may require protection from competitive bryophtyes, though some moss may be beneficial initially for moisture retention. Choose the right lichen for the environment. Sensitive species have low tolerances for pollutants. Lastly, patience. Lichens are incredibly slow growing. It may take several years to notice a change in some species. Even longer for substantial growth. Something to think about next time you’re out of TP and you decide to wipe with an Usnea.

References

McCune, B., C. Derr, P. Muir, A. Shirazi, S. Sillett, W. Daly. 1996. Lichen Pendants for Transplant and Growth Experiments. The Lichenologist 28 (02), 161-169

Gustafsson, L., K. Fedrowitz & P. Hazell. 2013. Survival and vitality of a macrolichen 14 years after transplantation on aspen trees retained at clearcutting. Forest Ecology and Management 291, 436–441

Frey, B., C. Scheidegger & S. Zoller. 1995. Transplantation of Symbiotic Propagules and Thallus Fragments: Methods for the Conservation of Threatened Epiphytic Lichen Populations. Mitteilungen der Eidgenössischen Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft 70, 41-62

Kon, Y., Y. Ohmura. 2010. Regeneration of Juvenile Thalli from Transplanted Soredia of Parmotrema clavuliferum and Ramalina yasudae. Bulletin of the National Museum of Nature and Science 36(2), 65-70.

Leave a Reply