The Predicament

We find ourselves now in the grip of a dilemma:

How can we maintain prescribed burning practices and, at the same time, reduce the amount of damage to lichen populations?

This blog post outlines what we know about the current state of research on lichen recovery after fire and how this relates to the complex management strategies implemented in the South Puget Sound Prairies. In previous posts, we touched upon the importance of lichens, challenges and methods of restoration, and current research into the subject. This post aims to summarize existing literature on prairie lichen restoration after fire and discuss future possibilities and opportunities for increasing healthy lichen populations after prairie burning, which is an integral part of management of the remaining prairie habitats in the Puget Sound bioregion.

Due to the sluggish growth rate of these peculiar and beautiful organisms, current research and findings concerning prairie lichen communities and their resurgence after fire treatments are only in their early stages. We do know however that the presence of lichens in prairies is important on many levels.

There is much yet to be understood regarding prairie lichens and their role in maintaining native species populations of certain grasses, wild flowers, insects and small mammals, but there are several studies that allude to their importance and we are just at the tip of the iceberg. Burning too is an important function in maintaining certain populations. While healthy for the prairie, burning immediately destroys the delicate lichen among other species that habitate in the prairie. More research needs to be done into the relationship between fire and lichens. Proposed methods for minimizing species loss include the establishment of fire refuges for vulnerable species, the practice of mosaic burning rather than large plot burning, and efforts to ensure low fire intensity. (Smith et al., 2012; Calabria et al., 2015).

Check out another great blog by our cohorts for more in-depth dicussion on the effects of prairie fires on bryophyre and lichen communities:

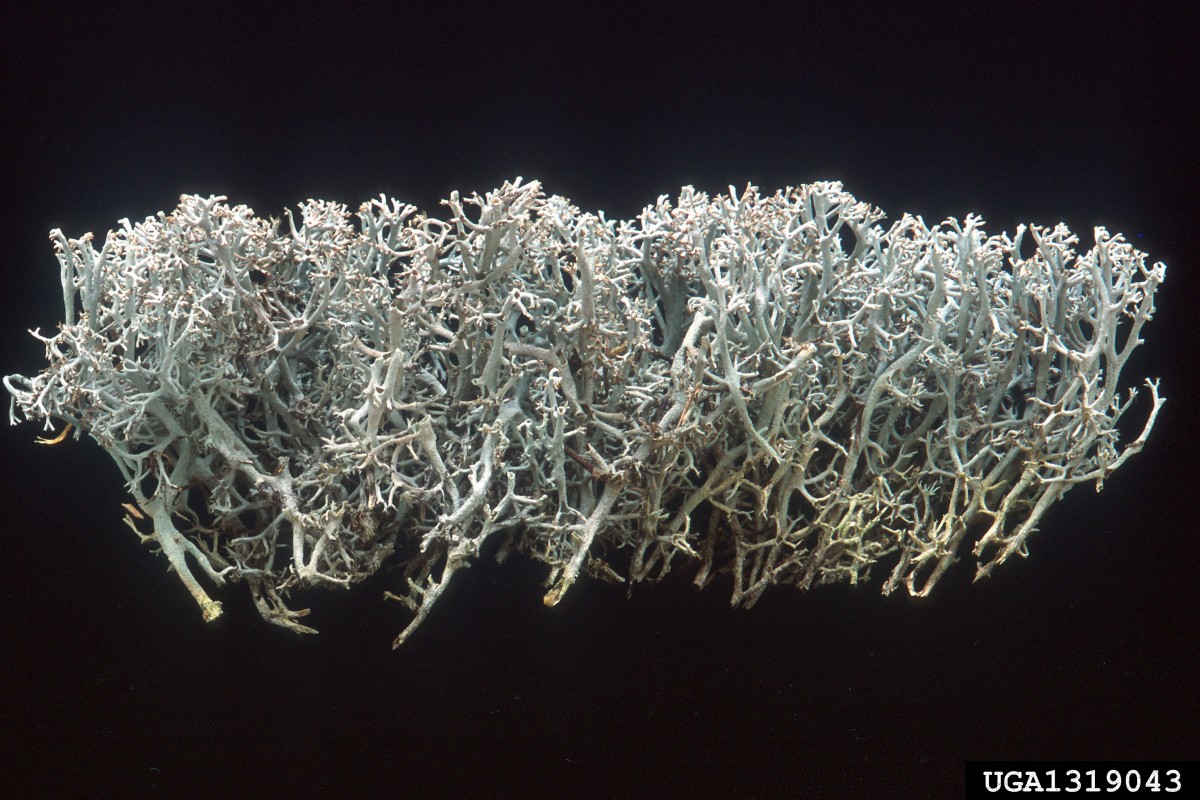

Closeup of the lichen Cladina rangiferina collected by plant physiologist Joanne Romagni. Click the image for more details.

WTF can be done, you ask?

As has been said, lichens facilitate the conversion of CO2 to O2 via photosynthesis by providing a shelter to the algae contained within the thallus, thus allowing this process to occur much more widely than just the algae alone which wouldn’t survive in certain conditions without the protection of the fungal hyphae. Also, due to the lack of a waxy cuticle, lichens absorb everything from the surrounding air directly through the thallus. They are able to absorb pollutants as well as indicate the air quality of the surrounding environment. Studies have shown that some species of lichens are

extremely sensitive to environmental change, making them a major reason for their popularity as bioindicators for natural resource assessment (e.g., Nimis et al. 2002). By observing the lichens, we could eventually learn much more about the ecological impacts of air pollution by assessing certain trends in lichen populations.

We have already proposed that in order to better understand the growth process of lichens, chemical analysis of soil and other substrates must be undergone before and after burning, rain, snow, etc. In addition, pH levels should be tested to observe what best conditions are required for optimum revival? Could there be an optimal time of year in which to experiment with lichen transplanting. There are no trees in the prairie so the lichens would be fully exposed at certain times of the year depending on the height of the grasses or other vascular plants.

Patiently, we must continue to research the problem at hand for years to come so that hopefully we come to a more thorough grasp on the benefits of lichens in general and the role they play in prairies, the post-burn recovery process and improved methods for how we can continue to aid in the restoration and maintenance of the prairie lichen population of the Pacific Northwest as well as other populations around the world.

For a wealth of fascinating and related information on Lichens, check out any of the following links:

- Wanna get involved? Click here——-> South Sound Prairies Center for Natural Lands Management – Washington Program

- Grow your own! Lichen Lovers

- Other cool blogs our classmates participated in: Opal Creek Wilderness Annotated Checklist Project, Evergreen Parking Lot Bioblitz, and once again, Fire effects on Prairie Bryophyte and Lichen Communities

Works Cited

- Calabria, L. M., Arnold, A., Charatz, E., Eide, G., Hynson, L. M., Jackmond, G., … Villella, J. 2015. A Checklist of Soil-Dwelling Bryophytes and Lichens of the South Puget Sound Prairies of Western Washington. Evansia,32(1): 30–41. doi:10.1639/079.032.0106

- Nimis, P. L., Scheidegger, C. & Wolseley, P. A. 2002. Monitoring with lichens – monitoring lichens. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 408 pp.

Leave a Reply