At Opal Creek, our goal was to collect, identify, and synthesize a list of as many known Opal Creek species as we could in the four days we were there, as well as potentially record species previously not known to inhabit this particular old growth forest. Because of the age and health of old growth (compared to other, younger forests), many rare lichen and bryophyte species occur in abundance in this forest. Especially because of its position in Cascadia (the bioregion of the Pacific Northwest including Washington, Oregon, and parts of Canada), Opal creek has some of the most diverse moss flora in the world (Henkel, 110).

This process included taking guided tours to sites with ecologically varying habitats and collecting bryophyte and lichen samples, recording important diagnostic information such as location description, GPS coordinates, substrate, elevation, and personal collection ID number. Once we were back at the main campsite, we used keys, microscopes, and other lab tools to identify our collected samples in the commissary building. On our final lab day, we put together a master list of every species collected and identified at Opal Creek.

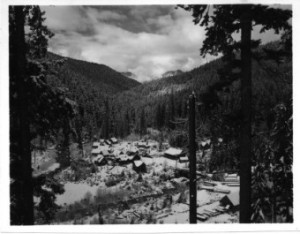

The housing lodge at Opal Creek

The class split into eight groups. Each group was responsible for collecting and identifying several species of one group of bryophytes and one group of lichen. In the mornings at Opal Creek, the groups would split up to go on collecting hikes and expeditions (locations according to the habitat needs of each moss/lichen type). Hikes were led by experts on the species present at Opal Creek, many of which were Evergreen graduates. Having knowledgeable professionals present was incredibly helpful in identifying trickier species. Keying and identification went smoothly back at camp, until our second day in the lab. Shortly after setting up on Wednesday, we lost power to the commissary building where the lab equipment was set up. Because the commissary relies on solar panels, reliable power was not a luxury we could take for granted. For the rest of the day we were without direct power to that building. During the down time, students went on more collecting trips, studied their species, and worked on drawing and descriptions for their collections.

My personal monograph of Nephroma bellum

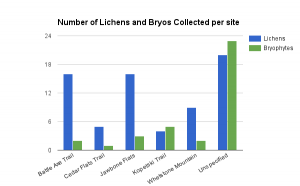

After a few hours, power was rerouted from the lodge (which runs on hydroelectricity) to the commissary via extension cords, and we were back in action. At the end of the day, a master list of every lichen and bryophyte collected was created. A species list was not the only thing we took away from Opal Creek. As well as learning about the vast biodiversity of bryophytes and lichens at the site, students were able to acquire important field skills such as sight recognition, search methods (based on target species), time management, preparation, team work and being able to improvise when things go wrong. Spending four days straight at Opal Creek gave us a feel of what it’s like to be a field biologist,

and we were able to encounter and overcome some of the same obstacles a professional might.

The only other notable setback was our lack of time at Opal Creek. Four days was

barely enough to scratch the surface of the bryophyte and lichen biodiversity present at Opal Creek. If we had several more weeks, or even a few more days, we could have accomplished so much more. However, I think it’s safe to say that the Evergreen State College Bryo and Lichens of the PNW program achieved its goals, as well as collectively gained several important field skills. Our time at the beautiful, pristine Opal Creek was definitely not wasted.

References

Henkel, William B. “Cascadia: A State of (Various) Mind(s).” JSTOR. Chicago Review, Vol. 39, No. 3/4, A North Pacific Rim Reader (1993). Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Henriksson, Elizabeth. “Nitrogen Fixation by Lichens”. JSTOR. Oikos, Vol. 22, No. 1 (1971). Web. 22 Nov. 2015.

Recent Comments