This blog is written and produced by students of “Bryophytes and Lichens of the Pacific Northwest” an ecology and field botany oriented program focused on exploring the diversity of lichens and bryophytes of the Pacific Northwest. Specifically, this blog focuses on the creation of an annotated checklist for the Opal Creek Ancient Old Growth Forest. Each of us will be writing a blog post to outline our experience studying the amazing diversity of bryophytes and lichens found at Opal Creek.

We hope you enjoy our blog, and stay tuned for more updates on our project!

- Bethany, Kelsi, Wyatt, Jenny, Patrick, and Will.

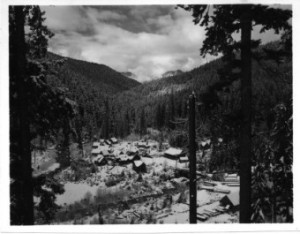

Opal Creek Wilderness is an old growth forest situated in the heart of Oregon near the Cascade Mountains. This wilderness area represents some of the last old growth forest in all of Oregon, and has withstood several forest fires (which are low intensity and are natural and essential for a healthy true Old Growth Forest). Its history is filled with conflict between settlers, miners, native residents, as well as conservationists before it became a federally protected wilderness area on Sept 20th, 1996 after a 20 year battle. Opal Creek’s rich natural history attracts over 20,000 visitors annually. It is a recreational area as well as an educational opportunity, and a Native American cultural site. Opal Creek was first inhabited by the Santium Molalla tribe who, camped in the Jawbone flats during the summer time. There is some evidence that the nearby Whetstone Mountain was retreated to for vision quests (History & Ecology, Opal Creek Wilderness Center) Also, the surrounding ‘Whetstone Mountain Trail’ was most likely a common trade route for indigenous tribes around the Pacific North West and is significant to the lifestyles of the original people of the PNW.

This region remained practically pristine until 1859 when miners discovered gold, and in 1930 “Grandpa” James P. Hewitt began official construction of the Jawbone Flats mining camp. Mining on Jawbone Flats continued until 1992 when attention was called to preserve the Opal Creek area by a conservation group called ‘Friends of Opal Creek’ which established itself in 1989. When mining ceased the Shiny Rock Mining Company gave Friends of Opal Creek all 151 acres of their land for preservation. Present day Opal Creek Wilderness spans upwards of 35,000 acres, some of which is federally owned, some privately owned by the conservation group. Opal Creek is an important place geographically, ecologically, and culturally.

Fungi, bryophytes, and lichens make up a majority of the biomass at Opal Creek Wilderness. These organisms are essential to the diversity of life found in this biosphere, as well as many others around the world. This is why Opal Creek Wilderness is the perfect place to explore the range and extent of species of the bryophytes a lichens. The most efficient way to categorize and keep track of organisms is by using an annotated checklist.

(An annotated checklist is just exactly as it sounds: it is a checklist of species in a specific area with notation about the species and its environment.)

Right-

Right-  JawBone Flats – The History and Ecology of Opal Creek Wilderness

JawBone Flats – The History and Ecology of Opal Creek Wilderness

Left- Cladonia cristatella. Rock substrate.)

Lichens are one of the few organisms that can ‘fix’ nitrogen into a usable organic form. All organic life requires fixed nitrogen to operate. Opal Creek is a useful place to study specialized lichens because of the nature of diversity in old growth forests as well as that old growth forests have almost entirely disappeared from the planet. There are very few true old growth forests left, therefore fewer and fewer environments in which to discover the beautiful diversity that exists in lichen and bryophyte populations.

Lichens are basically sponges for nutrients and water. When lichens fall they add components -like nitrates, polyphosphate, and Sulphur- to the soil. Lichens are a popular food source utilized by animals. It is a popular snack for Elk, Deer, and small mammals like squirrels in harsh winters. Some lichens have specialized structures on the bottom of the thallus where it connects to its substrate that are called rhizines. These lichen are popular with birds who use it as efficient nesting material

Top left: Parmelia sulcata has special rhizines that are Velcro like and is popular among birds for efficient nest building because of this feature. wikimedia commons

Top right: A bird uses lichen to build a strong weather worthy nest. Pintrest.com

Bottom left: A close up of Parmelia sulcata’s velcro like rhizines.

Lichens are pollution sensitive. Some lichens are bio indicators that can demonstrate the relative pollution in an area, by understanding the pollution tolerance of species we can estimate the amount of pollution in a habitat inferred by which lichens are present. More rare or pollution sensitive lichens grow in relatively pristine areas whereas pollution tolerant lichens can survive in habitats with higher levels of pollution (e.g. parking lots, Chernobyl). This is another example of Opal Creek’s exclusive habitat. It is a host to many species of sensitive and relatively rare species that one cannot see or study in many other areas around the world because of its pristine and old growth qualities.

Bryophytes are just as important to a thriving old growth habitat. Mosses, Liverworts, and Hornworts are organisms that may be highly specialized to old growth trees and ecosystems. Bryophytes are home to microorganisms and are a basic but enormous producer in an old growth forest. (More on Bryophytes to be covered in future blog posts.)

Our group is thrilled to utilize and eventually work on identifying and filling an annotated checklist with identified species in the Opal Creek Wilderness area. This field trip and checklist gives us opportunities to refine our collection techniques and field skills. We are also excited to take advantage of the opportunity to explore the reaches of bryophytes and lichens alike in an old growth forest. More to come soon so keep up with our project to learn more about Lichens and Bryophytes of the PNW and other exciting and nerdy news.

This video is funny and informative about great Opal Creek history.

(all photos and statements are available for noncommercial reuse.)

Opal Creek Forest Center, Representative. “History and Ecology, OCW.” Opal Creek Forest Center, n.d. Web. 11 Oct. 2015.

Calabria, Lalita. “Bryophytes and Lichens of the PNW.” Lecture Sept-Oct. Evergreen SC, Olympia. Web.

Forest Service, USDA. “Opal Creek Wilderness.” Www.fs.usda.gov. Federal Government, n.d. Web. 11 Oct. 2015.

“Ecology and History of Opal Creek.” Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center, n.d. Web. <http://www.opalcreek.org/history-ecology/>.

McOmie, Grant. “Travel Oregon.” Opal Creek. Travel Oregon, n.d. Web. 12 Oct. 2015.

Richard, Terry. “Opal Creek Wilderness – Where Nothing Happens.” Blog.oregonlive.com. The Oregonian, 21 Oct. 2008. Web. 12 Oct. 2015.

Recent Comments