Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

Genus: Fulica

Fulica americana

Introduction: The American Coot is the most abundant of 5 Rallidae species found in Washington (Paulson, D., 2019). It is a fairly easily identifiable bird due to its simple black and grey plumage and distinctive, chicken-like beak shape. The beak extends onto a hard red helmet on the forehead that may protect it during foraging and from other coots. It has notably large lobed feet used for paddling and, during breeding season, fighting. There is slight size sexual dimorphism as the females are slightly smaller, but the two sexes’ plumage is largely indistinguishable. Female coots weigh 427-628 grams, while the larger males average at 576-848 grams. Their wingspan is 58-71 cm (Greenfield, T., & Hall, P., 2013).

Range Map provided Data provided by NatureServe in collaboration with Robert Ridgely, James Zook, The Nature Conservancy – Migratory Bird Program, Conservation International – CABS, World Wildlife Fund – US, and Environment Canada – WILDSPACE.

American coots have both migratory and resident populations depending on the conditions of the region they live in. Washington is temperate which allows them to remain here year-round without high offspring mortality rates. The breeding region of migratory populations follows the trend of birds breeding at higher altitudes as mentioned in our class textbook, “Handbook of Bird Biology” (p. 466).

Photo of parent coot on nest by MDC Staff, courtesy of Missouri Department of Conservation.

American coots favor different habitats depending on the season. While breeding they prefer shallow wetlands with lots of vegetation to make a nest and hide within (Nieoczym, Marek, and Janusz Kloskowski, 2018). They will seek out larger lakes while molting so that they can stay out on the lake where they are less vulnerable to land predators until their wings are more functional. During the winter the range of habitats is much broader– both marine and freshwater bodies of water are habitat options for an adult coot. This versatility attributes to the success of the American Coot, and its large range (Alisauskas, R. T. and T. W. Arnold, 1994).

American coots are omnivorous and are not at all fastidious–they will eat most things that they have the opportunity to. Their diet regularly consists of algae, grass seeds, insects, and small fish (Driver, E. A., 1988).They do not vibrate their bills through the water like ducks since their bill is more chicken-like, but they do regularly poke it through the water to stir the water up and reveal food.

Attached below is a personal clip taken at Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge. It shows the foraging movements of a pair of American Coots.

https://1drv.ms/v/s!AlKP6QWoBooJok2CT-7ECutnKO2_

American Coots do not have a true song. Their calls are typically short, raspy, and repetitive.

Male and female coots have different alarm calls–the male’s is more sharp and guttural, and the female’s is more of a cry (Beletsky, L., 2018).

Audio of a classic American Coot call, recorded by xeno-canto user Paul Marvin:

Audio of an American Coot alarm call, most likely a male judging by sound. Recorded by xeno-canto user fernando mondaca fernandez:

Both males and females are aggressive, particularly males during breeding season. Male coots will fight each other by rising up in the water and using their strong, lobed feet (Zhang, W., Liu, W., & Ma, J., 2011). Migratory populations typically only travel in mated pairs during the breeding season, while resident populations remain pair-bonded to protect territory year-round (Brisbin Jr., I. L. and T. B. Mowbray, 2002).

Photo taken by Tom Grey

*Note: These are Eurasian Coots and therefore lack the red spots on their beaks. However, Eurasian Coots are very similar and were only recently recognized as a separate species (James Neitzel, personal communication, Feb 21, 2019).

Laying/offspring behavior:

Photo of coot offspring and parent taken by Flickr user Mike Baird

Coots exhibit parasitic nesting behavior. Females that don’t have stable territory will lay their eggs in other coot’s nests. 40% of coot nests have an egg within them that doesn’t belong to the female that made that nest. However, recent evidence indicates that female coots have been building a system to recognize parasitic offspring by comparing them to the behavior of their first-hatched egg. This is an effective system because due to the time frame in which females lay in other nests, the first-hatched chick almost always belongs to the nest mother. Considering that many other birds are successfully parasitized by very different species whereas American Coots are only parasitized by their own species, this ability to distinguish offspring is impressive (Shizuka, D., & Lyon, B. E., 2009).

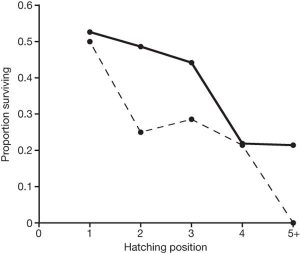

Graph showing likelihood of chick survival based on when it hatches–solid line is host chicks, dotted line is parasitic chicks. 36% of host chicks and 19% of parasitic chicks survived in these broods.

Clutch sizes are larger than the number of chicks that a female can sustain, so there is fierce competition between chicks–they’ve even been known to kill each other directly, though more commonly they’re selected through food competition (Alisauskas, Ray T., 1986, p. 84). More brightly colored chicks are favored by parents, despite their coloring making them more vulnerable to predators (Lyon, B.E., 1994).

Alisauskas, Ray T. “Variation in the Composition of the Eggs and Chicks of American Coots.” The Condor, vol. 88, no. 1, 1986, p. 84., doi:10.2307/1367757.

Alisauskas, R. T. and T. W. Arnold. (1994). “American Coot.” In Migratory shore and upland game bird management in North America., edited by T. C. Tacha and C. E. Braun, 127-143. Lawrence, KS: Int. Assoc. Fish Wildl. Agencies, Allen Press.

Barnes, J. G., & Gerstenberger, S. L. (2015). Using Feathers to Determine Mercury Contamination in Peregrine Falcons and Their Prey. Journal of Raptor Research, 49(1), 43-58. doi:10.3356/jrr-14-00045.1

Beletsky, L. (2018). Bird songs: 250 North American birds in song. Bellevue, WA: Becker & Mayer! Books.

Brisbin Jr., I. L. and T. B. Mowbray (2002). American Coot (Fulica americana), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

The Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. (2016). Handbook of Bird Biology (3rd ed.). Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, John.

Driver, E. A. (1988). Diet and Behavior of Young American Coots. Wildfowl,39, 34-42.

Greenfield, T., & Hall, P. (2013). A field guide to birds of the Pacific Northwest. Madeira Park, B.C.: Harbour Publishing.

López-Islas, María Eugenia, et al. “Biological Responses of the American Coot (Fulica Americana), in Wetlands with Contrasting Environmental Conditions (Basin of México).” Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, vol. 80, no. 6, 2017, pp. 349–364. US National Library of Medicine, doi:10.1080/15287394.2017.1325422.

Lyon, Bruce E., et al. “Parental Choice Selects for Ornamental Plumage in American Coot Chicks.” Nature, vol. 371, no. 6494, 1994, pp. 240–243., doi:10.1038/371240a0.

Nieoczym, Marek, and Janusz Kloskowski. “Habitat Selection and Reproductive Success of Coot Fulica Atra on Ponds under Different Fish Size and Density Conditions.” Hydrobiologia, vol. 820, no.1, 2018, pp. 267–279., doi:10.1007/s10750-018-3664-2.

Paulson, D. (2019, February 27). Birds of Washington. Retrieved March 10, 2019, from https://www.pugetsound.edu/academics/academic-resources/slater-museum/biodiversity-resources/birds/birds-of-washington/

Ridgely, R.S., T.F. Allnutt, T. Brooks, D.K. McNicol, D.W. Mehlman, B.E. Young, and J.R. Zook. 2003. Digital Distribution Maps of the Birds of the Western Hemisphere, version 1.0. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia, USA.

Shizuka, D., & Lyon, B. E. (2009). Coots use hatch order to learn to recognize and reject conspecific brood parasitic chicks. Nature, 463(7278), 223-226. doi:10.1038/nature08655

Zhang, W., Liu, W., & Ma, J. (2011). Territory and territorial behavior of migrating Common Coot (Fulica atra). Journal of Forestry Research, 22(2), 289-294. doi:10.1007/s11676-011-0164-x

American Coots are Least Threatened status and are considered pests in some states because their feet and feeding pattern causes crop damage. They are often used as a monitoring species for toxicity levels because they’re common, their distribution is widespread, and waterbirds have much higher toxicity levels than other birds. Several notable recent toxicology studies have used American Coots as a subject, such as López-Islas’ “Biological Responses of the American Coot (Fulica Americana), in Wetlands with Contrasting Environmental Conditions (Basin of México).” (pp. 349-364), and Joseph G. Barnes’ “Using Feathers to Determine Mercury Contamination in Peregrine Falcons and Their Prey” (p. 50).

Lily Messinger is a biology student at Evergreen State College. This page was created for her Birds: Inside and Out course in 2019.

Leave a Reply