“Commodities had long existed and people exchanged them in various ways in previous social systems. But the social changes that were ushered in with the arrival, growth, and spread of capitalist production moved societies toward what sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein call ‘the commodification of everything’” (Longo, Clausen, and Clark 146).

This is never more true than in the fishing industry today. Where not only are the species caught commodities, but the very act of fishing is a commodity. You can buy and sell fishing trips, you can buy and sell fishing quota, boats, and gear.

It is not a surprise that fisheries management is not the tragedy of the commons, but of the commodity, for anything existing in the Capitalist socioeconomic system is prey to commodification. “The tragedy of the commodity arose with the emergence of capitalist development. As a growth-dependent economic system, capitalism pursues endless accumulation. Thus, it reproduces itself on an ever-larger scale” (Longo, Clausen, and Clark 175). We can clearly see the issue here. As the industry pursues that growth, their catch grows and grows until stocks can no longer sustain themselves. When that happens fishing stops and the industry crumbles in on itself, or they seek out farmed fish another byproduct of commodification.

If the problem is the social structure and system put in place, how can we change our fishing management before the salmon are gone? Before all that is left are farmed fish and failing ecosystems?

Maybe the answer isn’t in the hard science of the fisheries, maybe the answer lies within our relationships to each other, and to our environments.

To understand the answer, we first have to realize that no answer is universal, and in fact there may be many answers to this question. Each ecosystem requires different moving parts and solutions will be a response to those missing or damaged parts.

Some answers presented by Longo, Clausen, and Clark include:

- “Transcending the Tragedy of the Commodity” (178). We need a deep and lasting socioeconomic change, moving away from Capitalism and Globalization (in some regards). This includes severing ties with the political agenda’s present in today’s world, and pursuing a different narrative. We also need a consumer movement; in which you do not consume or buy fish products that aren’t sustainable or near you.

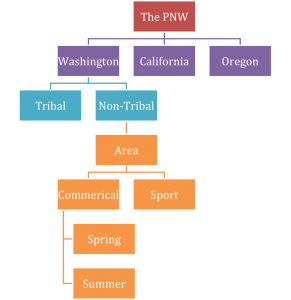

- “Forging the Future and Mending the Rifts” (188). Community Management and moving away from state control. When individual communities are given direct control over economies and ecological planning they can create a more just system. Not just political democracy but also economic democracy. Those who produce surplus must also decide how to distribute surplus. Workers must be in control of production in food systems, not small groups of individuals where the power is concentrate. The bottom line is having de-centralized power and give power back to all the players who participate in the resource.

- “Beyond Capital: A Resilient, Sustainable, and Just Social Metabolic Order” (198). We do not need to return to the past but there are some lessons from those past civilizations that we can learn today. Capitalism is not rooted in stone, in fact it’s easier to change a political impossibility (capitalism) than a biophysical impossibility (pollution killing us). WE cannot replace Capitalism with another form of nature and labor exploration.

When it comes to reform in fish management, we have to reform the social barriers, and the economic barriers. We need to bring communities back together and untie our hands from the shackles of the state run social systems.

The biggest solution (that I see) is stopping worker exploration in the food system (and most industries), give those workers the production management, allow workers to decided how surplus is distributed, and stop using our natural world for the base of all commodities.

The political barriers to these changes are possible. The impossibility is the recovery of our earth from the point of no return. No earth=no humanity.