I had the chance to visit the Nelson Provincial Museum, which offers an extensive exhibit on Maori culture throughout time in the region. I found it insightful and thought provoking to read the stories and bits of history, and was fascinated by the artifacts presented.

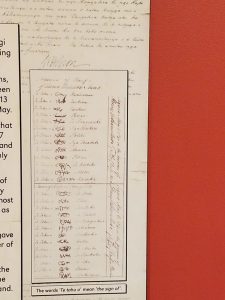

One of the first topics presented was about the Treaty of Waitangi. The treaty was drawn up by William Hobson who was appointed by the British government to take control of the government in Aotearoa/NZ. The first signing was at Waitangi (hence the name of the treaty), and was first signed by 40 rangatira (chiefs) on the 4th of February, 1840. The treaty was then carried around to be signed by as many rangatira as possible.

In this region, the treaty was signed at Queen Charlotte Sound by 27 chiefs in May 4th 1840, Rangitoto by 13 chiefs on May 11th, and Cloudy Bay by 9 chiefs on June 17th. The rangatira at Cloudy Bay debated the treaty for a long time before signing as they were scared of losing land (rightly so).

A lot of the modern debate over the treaty comes from the fact that while about 500 Maori did sign the treaty, 39 rangatira chose not to sign. However, even though they refused the document they are still forced to oblige with the treaty’s regulations. Reading greater in depth about how the British government manipulated the Maori made my care for their community grow even larger as I was able to get a more in-depth understanding of their struggles.

One story told at the Museum was about the Maori’s loss of lands in Motueka, the location of the marae that I visited on Waitangi day. These lands are called the Te Maatu lands (meaning ‘Big Wood’ due to their dense forests), and they were under protection of the treaty by the name of Whakarewa native reserve. Approximately 375 acres were unlawfully seized by the British without the consent of the Maori population. This was done by a sneaky bypass of the treaty, as Governor Grey was appointed by the crown to take the land under their control in order to establish schools. The seizing document reads that the land can be removed from the iwi’s ownership “so long as religious education, industrial training and instruction in English language shall be given.” It claimed that the transfer of power over the land would benefit the Maori people by acclimating them into colonial culture. Here I see an example similar to the 19th century racist ideals present in Racial Indigestion, as the British government actively strived to consume the lifestyle and traditions of the Maori by white-washing. This event is also quite comparable to the conversion of culture present as America was taken over by colonization, without acknowledgement of the wisdom and meaningful practices important to the lives of those who had already occupied the land. The British felt as though they were doing the Maori a favor by furthering the ‘progress’ of their society with technical know-how and ‘proper’ religion, while the Maori were devastated by the attempted decimation of their way of living. After familiarizing myself with the methods used by colonial government to try to devour the Maori civilization, I have so much appreciation for the Maori ancestors, who decided that they would always try to teach the settlers how to care for the land in the ways they had practiced for years before their arrival. It is because of this commitment to kindness and education that the Maori population today is still thriving and striving to work together with the modern public and develop cultural understanding.

Before settlement, the Maori were true artists in everything they created, crafting beautiful artifacts for simple everyday clothing and tools. They were keen on patterns that represented the way the earth flows, and their interactions with the world. While today they still do produce beautiful things like they used to to keep traditions alive, they now wear the clothes and use the tools that modern technology has made. Below are photos of some of my favorite things I saw.

Bag woven from flax leaves. Flax became industralized after British settlement, due to the fact that it was reported to the crown as being a major useful export. The international industry saw many ups and downs and is virtually non-existent now, though flax is still grown widely and used within the country.

Weeders for the garden… looks so much more fun to use (& more sustainable) then the plastic/alluminium ones we have now

Woven by the women at the Te Awhina Marae in Motueka. Symbolic of protection, strength, and guardianship