In conjunction with preparing my ILC, continuing to curate a reading list and volunteer or community opportunities, this week I have delved head-first into the academic research required in understanding the complexities and interdisciplinary nature of food insecurity, higher education, and socioeconomic status.

I decided to start by reading Endless Appetites by Alan Bjerga, a text that explains the international hunger crisis in regard to the commodities system, and watching A Place at the Table, a documentary about food insecurity in America. In order to coherently synthesize what I learned, this week I am going to take a page from the ComAlt SOS book and put these two seemingly different resources in conversation with one another.

It’s only Week 1, and I have already encountered the notorious and villainous dynamic duo at the route cause of every major issue in the modern world, including food insecurity. Any liberal’s most hated love affair: Big Business and Government. Are you shocked? Me neither.

Who are the Deciders?

“The price of food – the cost of a loaf of bread in a supermarket, brought to you via a global system of farmers, purchasers, processors, distributors, retailers, and consumers… the system that in many ways decides who gets to eat and who doesn’t.” (Bjerga 2011: 4)

Regardless of a severe climate changes and an increasing population, there is enough food produced in the world to feed everyone. So the question of food insecurity and hunger, both nationally and globally, becomes, who decides who gets to eat?

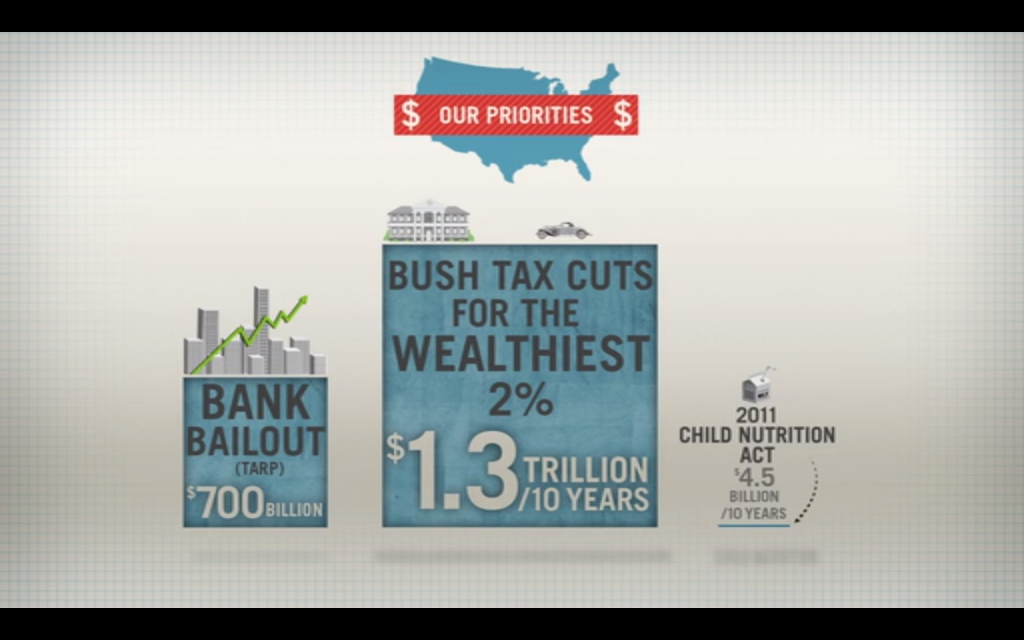

In the United States, the legislation allocates funds toward addressing hunger faced by the elderly and impoverished families with the hopes of slightly correcting the severe inequality faced by Americans. Although one might then assume that government decides who eats, because legislation and government funding is often the most effective way to address these issues on a national scale, they are too often thwarted or muted due to special interest lobbyist. As depicted in A Place at the Table, the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010 was initially a bill which allocated $10 billion over 10 years to create healthier meals in public schools and allow more children access to benefit programs. But by the time it got past the big agriculture lobbyists, the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act allotted a measly $4.5 billion, half of which were simply funds taken from the SNAP benefits program.

So it can be argued that both the (dysfunctional) legislature as well as big corporations ultimately decide who gets to eat in America.

This conclusion leads me, of course to more questions. What is our country’s history with food security legislation? What are all of the current federal programs in place? And of course, do any of these programs benefit students and children pursuing a higher education?

Corn v. Carrots, Soy v. Strawberries

“The United States, the world’s richest nation, is also the biggest exporter of low-cost, bulk staple crops, even as its organic foods consumption rises from a minuscule fragment of grocery sales in the mid-1990s to about 41% today… Who receives subsidies, as well as the subsidies themselves, can be poorly targeted. Subsidy recipients worldwide have included noted farmers… and at least a half dozen billionaires according to U.S. records.” (Bjerga 2011: 139, 152)

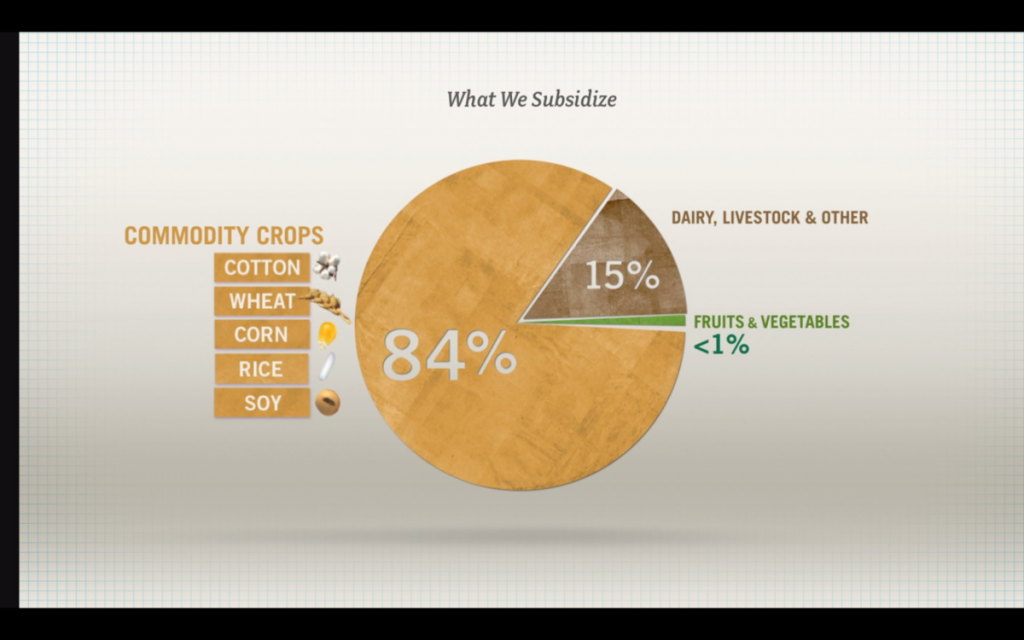

As explained in A Place at the Table, farm subsidies were an emergency response policy in light of the Great Depression at which time the primary beneficiaries of these subsidies were small family farms. However, over time, the subsidies went to large, corporate agribusinesses that produce the staple crops: wheat, corn, soy, cotton, and rice, creating a trend of higher priced fruits and vegetables, and lower priced processed foods high in fat, sugar, and simple carbohydrates. So logically, making food less expensive, more accessible and healthier for those who can only afford nutritionally void food could mean shifting subsidy funding away from these big staple crop corporations, and towards smaller produce farms.

Simple, right? Well, no. Not only because of that pesky corporate money I mentioned earlier, but as I read Endless Appetites, I remembered how important healthy trade is for the United States economy. Subsidizing some of our most valuable exports must be, to some extent, beneficial to the overall economy and GDP growth in the United States.

So, does the overall economic stability outweigh the benefits of shifting funds to ensure lower produce prices? In this instance, does overall economic stability benefit impoverished, food insecure students, or is it just the rich who reap the rewards?

Next week I will be exploring these questions along with, and as part of my learning objectives through additional texts, films, legislation and field work. See you all then!

January 18, 2017 at 5:17 pm

Hey there Natasha, Shani here

Let me preface with I did not do the seminar assignment. But you bring up points I think I can comment on.

First off:

“So, does the overall economic stability outweigh the benefits of shifting funds to ensure lower produce prices? In this instance, does overall economic stability benefit impoverished, food insecure students, or is it just the rich who reap the rewards?”

I think you know the answer to this. As we’re seeing, and have seen throughout history, the gap between food producers and and consumers has always been large, and stratified by those who can afford quality and/or exotic foods. I want to emphasize how true this is even for the food producers who often times cannot afford their own food. You see this among farm laborers and the farm owners. At least here in America this quality can find its place in the publics’ general romanticization of the struggling farmer- the farmer who doesn’t need anything from anyone and loves the druggery of scrapping by. Realistically though, this mentality does not reflect the actual cost of producing and transporting food. Additionally, the “15-20 cents/dollar” it takes to produce food highly undercuts the cost of labor, because labor is undervalued as a farm input, because historically speaking, farms have always been aided by the labor of the lowest class, for example slaves, illiterate immigrants being paid slave wages, etc.-

There’s a mentality at work, cultural norms, which until addressed, will continue to permeate. Now how deep we have to go to fully address these issues might even question the legitimacy of our economic system- capitalism. How can you commodify food? What is the real price of food? It’s true value in preventing dis-ease, creating community, connecting people to space- how do you quantify these facets? Why do we equate something which provides nourishment to an inedible piece of paper? Eating is not a choice, just as much as health is not a choice, it’s not an unnecessary product to be bought with our pocket change. So why do we force it? When we stratify food between people, we interfere with their sense of safety- isn’t doing so a threat to the community? Is forcing people to pay for food ethical? These are one the many things I think about during the day and I’ll be happy if you could shed some light on it.

Thanks for sharing~

Shani A

January 19, 2017 at 3:51 pm

Shani,

Thanks so much for taking the time to join my discussion!

I am 100% on board with what you’re saying.

Unfortunately I think that creating yet another anti-capitalist argument as a solution to the issue of food insecurity is only helpful in theory. What we’re working with today is a deeply ingrained system of commodification of food and capital vs. labor economic inequality. I’m interested in reconciling these two opposing systems -food as a necessity and food as a commodity- in order to present solutions for effective and practical change.

So my questions, then, become less of the philosophical nature and more economic and policy-oriented.

The questions you present are also ponderings I have regularly, though. Oh the complexity of the food system!

January 21, 2017 at 2:37 pm

Hey Natasha~

I agree, conversations like these shouldn’t live in the ether of theories, and they shouldn’t be stoppers to discussions just because they bring up capitalism and capitalism’s faults. I’ve thought about that point for a while and I believe if food is to be a commodity, it should be paid for through taxes- just like healthcare, just like water resources, just like education. Feeding people is an investment; if we force people to pay money towards necessities (things which everybody needs), we’re taking money that could be spent on luxury items (American made cowgirl boots) and spending it on under-priced requirements ($5/5# potatoes, are you kidding? That’s not representative of the true costs.). And so, taking this conversation out of theory and into practicum, I recommend that farms meeting certain requirements be paid by the government, with government benefits, healthcare, retirement, etc, funded by the subsidies we already dish out to monocrops. It’s the whole idea of “rent-poverty”, or the “rent-burden”, or whatever Bernie Sanders called it- essentially people only have money to pay for rent and the necessities and that’s it. They don’t have the income to absorb the true cost of things. Farms don’t have income to absorb the costs of being “eco-friendly”, so they externalize those costs into the environment and onto the public. People don’t have the income to pay the true price of food- so they externalize those costs into the environment and onto the public in the form of healthcare (silent starvation). However, if those costs were paid for by the public to meet everybody’s needs, people could invest into the commodity market again and jump start the economy. However, let it be known that I only vaguely know what I’m talking about concerning economics as I did not do too well in that portion of the IES program. So…..is what I’m suggesting socialism? Communism? No idea, but at least people will be fed…

I agree with you, these conversations should not remain in the ether of disgruntled anti-capitalists. Do you have any leads or opinions so far as to bridge the “two opposing systems -food as a necessity and food as a commodity”? I’d love to discuss it~

Thanks for the seminar Natasha, I look forward to your response~

Shani A