Author: stecol11

Why the Vast Coastal Prairies and Grasslands of California Exist

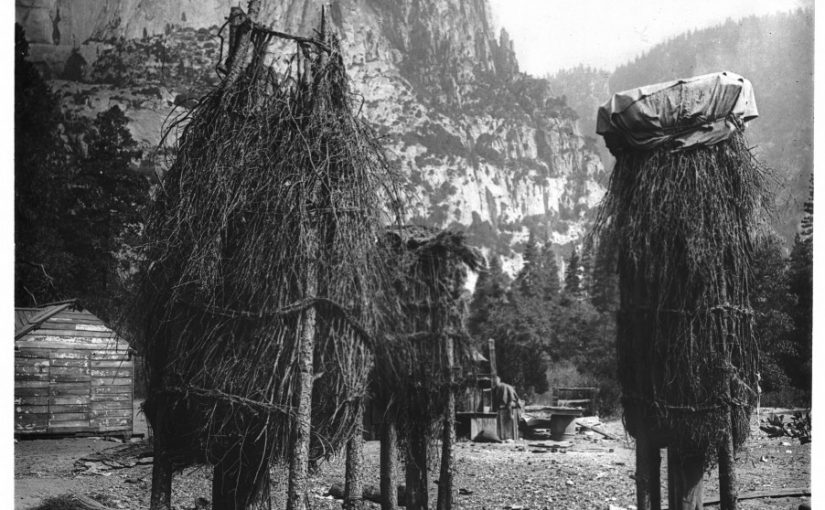

Photo from the California Bureau of Land Management

Much of the northern and central coasts of California are dominated by treeless prairies – these landscapes were intentionally cultivated.California coastal grasslands were burned every 1-3 years by Native Californians to increase harvests of grains, tubers, and bulbs.[1] These regular burnings also kept conifer trees from becoming established due to their inability to withstand fire.

Other famous areas of California were maintained by intentional burnings as well. In Kat Anderson’s ‘Tending the Wild’ she relays knowledge from a conversation with a man named James Rust who is Southern Sierra Miwok about Yosemite Valley.

‘In the old days there used to be lots more game – deer, quail, gray squirrels, rabbits. They burned to keep down the brush. The fire wouldn’t get away from you. It wouldn’t take all the timber like it would now. In those times, the creeks ran all year round. You could fish all season. Now you can’t because there’s no water. Timber and brush now take all the water. There were never the willows in the creeks like there are now. Water used to come right out of the ground. I remember Yosemite when I was a kid. You could see from one end of the Valley to the other. Now you can’t even see off the road. There were big oaks and big pines and no brush. There were nice meadows in there.’[2]

An artist from the late 19th century named Constance Gordon-Cumming warned of the danger of no human intervention in Yosemite Valley.

‘Indeed, there is a corner of danger, lest in the praiseworthy determination to preserve the valley from all ruthless ‘improvers’ and leave it wholly to nature, it may become an unmanageable wilderness. So long as the Indians had it to themselves, their frequent fires kept down the under-wood, which is now growing up everywhere in such dense thickets, that soon all the finest views will be altogether hidden, and a regiment of wood-cutters will be required to clear them.'[3]

Next time you are in Yosemite or coastal California, it’s worth taking the time to appreciate these gardens.

[1] http://www.sonoma.edu/cei/prairie/history/last_10000years.html

[2,3] Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. Univ of California Press.

Tukwila – Land of Hazelnuts

Photo Above: Coppiced Beaked Hazelnut

The Duwamish Tribe originally inhabited the city of Tukwila, which means the land of the hazelnuts. The hazelnut that was and is undoubtedly present in Tukwila is the beaked hazelnut, or Corylus cornuta. The beaked hazelnut is a thicket-forming shrub that reaches 12-15 feet in height. The beaked hazelnut can grow in damp rocky slopes, stream banks, and riparian areas. The nuts can be pounded into cakes with berries, meat, or animal fat, while the nut’s milk is delicious and reputed to treat colds and coughs.[1] People of many tribes in California picked hazelnuts by the basketful and at them raw or roasted; the Yurok pounded hazelnut kernels into a flour, added warm water, and used the mixture to nurse sickly children or ill person with weak stomachs and the Thompson Indians of southern British Columbia burned hazelnut bushes to enhance nut production.[2] The hazelnut was also an important source of building materials. The Miwok and Yokuts selected sprouts that were straight to be used for basketry and cooking utensils.[3]

[1] https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/pg_coco6.pdf

[2,3] Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. pg.172. Univ of California Press.

Red Alder

Photo Above: Young Red Alder Tree Being Burned for Brush Control

Red alder is the most common hardwood in the Pacific Northwest – its range extends from latitude 34 degrees north to 60 degrees north.[1] Alder timber is contemporarily used for face veneer, furniture, cabinets, paneling, edge-glued panels, core-stock and cross-bands in plywood, millwork, doors, pallets, woodenware and novelties, chips for waferboard, pulpwood, and firewood.[2]

Unknown to many, red alder was used extensively by many First Nations of America for many uses beyond its wood.

Inner bark of the alder was often ground and used in soups as a thickener while the outer barks were used as dyes and also as a treatment for headaches. Infusions made from the bark of red alders were taken to treat anemia, colds, congestion, and to relieve pain. Bark infusions were taken as a laxative and to regulate menstruation. The sap was applied to cuts and a poultice of the bark has been applied to eczema, sores, and aches. The twigs were made into infusions that served as liniments for sprains and backaches.[3]

Maybe in the future, the ingredients of canned soup will include alder bark.

[1] https://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/alnus/rubra.htm

[2] http://owic.oregonstate.edu/red-alder-alnus-rubra

[3] https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/cs_alru2.pdf

Pacific Crabapple

Photo Above: Pacific Crabapple Flowering in Early May on the Olympic Peninsula

Pacific crab apples are tall shrub or small trees that grow to be a range from 4 – 12 meters tall. The Pacific crab apple grows branches that have stiff, sharp, thorn-like spur-shoots. Their young twigs are curly and hairy, while their bark is brown, rough, and appears shredded.[1] The leaves of Pacific Crabapple are irregularly lobed, with toothed margins, pointed at the end. Branches have sharp spur shoots as is typical for apple trees. Its blossoms are white to pink. Fruits are small (10-15mm), oblong, and yellow to orange to purplish-red. Pacific Crab is usually propagated by seed and sown in fall. Fresh seed will germinate in late winter. Stored seed requires a cold stratification period for 3 months and may not germinate for 12 months. Cuttings of mature wood are best taken in November.[2] Crabapples contain a small amount of vitamin C (8 milligrams per 3 ounces of apple) and, depending upon the variety, they may contain signi – cant amounts of antioxidant flavanol compounds. The flavanol anthocyanin (the dark red pigment in some apples) and quercetin may help prevent cancer, heart disease, asthma and diabetes.[3]

[1] http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Malus%20fusca

[2] http://nativeplantspnw.com/pacific-crabapple-malus-fusca/

[3] http://www.uaf.edu/files/ces/publications-db/catalog/hec/FNH-00109.pdf

Camas

Next to salmon, camas, of the Camassia species, was the most traded food before the settlement of the Pacific Northwest by Europeans.[1] Camas bulbs were dug in the summer or spring and then either-pit roasted or boiled for up to two full days – this process would convert inulin present in the camas bulb into fructose.[2] Before the introduction of sugar, camas was used to sweeten and enhance other foods. Could camas be further reintroduced into modern cuisine as a local sweetener?

Camas was is distributed throughout the American West, from southwest Alberta, Montana, Wyoming, California, and British Columbia.[3] Many towns and regions carry the name of camas, such as Camas County in Idaho, the city of Camas and Lacamas Creek in Washington State, and Camas Valley, Oregon. One of the largest prairies in the region is at Joint-Base Lewis McChord in central-western Washington. Whilst driving pass the base, one can see hundreds of Garry Oak trees (Quercus garryana), a species that is in common association with camas prairies.

[1] Gunther, E. 1945, rev. 1973. Ethnobotany of western Washington. University of Washington Publications in Anthropology 10(1). University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington.

[2] https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/cs_caqub2.pdf

[3] https://plants.usda.gov/plantguide/pdf/cs_caqub2.pdf

Diverse Diets

About half of all modern American adults have one or more preventable chronic diseases.[1] Before colonization by Europeans, the diet of Native Americans was widely diverse. A partial list of plant foods eaten by native Californians, compiled by Kat Anderson, follows.[2]

Dry Fruits, seeds, and grains: walnut, hazelnut, California bay, buckeye, chinquapin, acorn, pinyon pine, sugar pine, gray pine, blue wild rye, California brome, wild oats, Indian ricegrass, coast tarweed, common madia, lupine, cockbur, California lomatium, woolly sunflower, peppergrass, chia, mule ears, witchgrass, cattail, valley tassel, desert ironwood, yellow pond lily, evening primrose, desert nama, white navarretia, arrow-grass, meadow foam, melic grass

Bulbs, corms, rhizomes, taproots, and tubers: bracken fern, wild onions, camas, soaproot, purple amole, balsam root, yampah, pussyears, mariposa lily, sanicle, common goldenstar, harvest brodiaea, Kaweah broadiae, blue dicks, ookow, snake lily, wild hyacinth, leopard lily, redwood lily, Washington lily, bear-grass, white brodiaea, golden brodiaea, ituriel’s spear, fire cracker flower, small ground-cone, Hartweg’s orchid

Leaves and stems: agave, yucca, mountain dandelion, wild onion, pigweed, angelica, wild celery, clover, cattail, tule, nettle, violet, American vetch, mule ears, narrow-leaved milkweed, red maids, jewelflower, tansy mustard, shooting star, dudleya, horsetail, soaproot, miner’s lettuce, bractscale, goosefoot, Indian rhubarb, California ground-cone, thistle, candy flower, nude buckwheat, cow parsnip, prince’s plume, fiddleneck, sweet cicely, watercress, water parsley

Fleshy fruits: manzanita, madrone, Oregon grape, wild strawberry, wild plum, islay, sourberry, lemonadeberry, wild currant, serviceberry, gooseberry, wild rose, elderberry, buffaloberry, desert fan palm, desert apricot, thimbleberry, blackcap raspberry, California blackberry, desert peach, salmonberry, huckleberry, purple nightshade, western chockecherry, wild grape, redberry, twinberry, bridal honeysuckle

[1] https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/introduction/nutrition-and-health-are-closely-related/

[2] Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. pg 244. Univ of California Press.

Muir’s “Wilderness”

Photo from Yosemite Conservancy

John Muir is regarded as a figurehead of the modern environmentalist and naturalist movement. He founded the Sierra Club, and lobbied Congress to preserve and create national parks such as Yosemite and Sequoia, which were both founded in 1890. Undoubtedly, he had a unique reverence for what he considered “wilderness”.

Writing for a publication produced by the California State Board of Trade in 1897, John Muir said the following, “God never made an ugly landscape. All that the sun shines on is beautiful, so long as it is wild; and much in every landscape is unchangeably wild, especially light, which falls everywhere.”[1]

What did ‘wild’ mean to John Muir? It is well documented that both the Yosemite Valley and the Sequoia National Park area were occupied by the Miwok, Yokuts, Salinan, Maidu and Wintun tribes for thousands of years,[2] and that Yosemite was intentionally burned to keep shrub down and promote black oak habitat. [3] The Yosemite Valley that Muir found so pristine was in essence the result of thousands of years of cultivation by Native Californians.

[1] “The Scenery of California,” California Early History: Commercial Position: Climate: Scenery. San Francisco: California State Board of Trade, 1897, 16.

[2]https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/berkeley/steward2/stewardc.hm

[3] https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/nature/upload/Status-Trends-Black-Oaks-2008.pdf

Acorns

The California black oak, tan oak, and coast live oak all yield delicious and edible acorns in large quantities. Before the arrival of settlers to the west coast of America, acorns were the second-most traded commodity next to salt.[1] Estimates of the beginning of intensive harvest of acorns date to at least 2500 BCE in Central California.[2] Acorns are more nutritionally and calorically dense than cereal grains. Settling farmers brought with them their favourite livestock and seeds, such as pigs, cattle, and wheat. As Euro-agrarian settlement took place all over California, the management of oak trees by Native Californians was halted. By intentionally burning the understory of oak trees, a strong acorn crop was more likely to be yielded. It’s documented that the Cloverdale Pomo, the Kashaya Pomo, the Wappo, the Yurok and Tolowa, the Luiseno, the Maidu, and the Ohlone all burned to manage and encourage oak habitat. [3]

[1] Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. pg. 286. Univ of California Press.

[2] Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. pg. 287. Univ of California Press.

[3] Anderson, K. (2005). Tending the wild: Native American knowledge and the management of California’s natural resources. pg. 287. Univ of California Press.