Vulpes Vulpes

Origin

Eurasia – intercontinential

Place of observation

Northwest Trek – Eatonville

Specs

Thereocephalic characters and their "pure animal" counterparts. The gentleman is a fashion-conscious art student and the lady is a glamorous self-portrait.

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: damn right! – Mammalia

Order: Carnivora

Family: Canidae

Genus: Vulpes

I’ve always been fond of this animal. I find their appearance, antics and vocalizations inherently charming. I chose it because I knew that it had an extensive history in culture and art. The fox has definitely made a name for herself cross-culturally as a notorious sass-master.

Since I had no previous experience with these animals, I didn’t know what to expect. I didn’t think that I would have the opportunity to interact with them in person and that I would have to watch them from a distance. I was able to take many notes on their physical behavior, but I never had the chance to “know them” personally.

Although the red fox is a petite creature, it is the largest of all fox species. An average adult measures 25-35 inches in body length (not including the tail) and weighs between 6 and 15 pounds. Its tail is usually more than half of its body length.

The fur is extremely fluffy. Its coat consists of two types of hairs: a thick undercoat of light short hairs and long, coarse guard hairs. Although red is the most common color, they can also be grey, brown, black, or a mix. The legs are usually black or brown and the fur on the face and belly is white.

Natural History

The red fox (vulpes vulpes) originated in the Eurasian continent around the Villafranchian period (1- 3 million years ago) and has since spread across the globe. This species can be found in Europe, Asia, North and South America, Northern Africa, and Australia. It is listed as a species of “least concern” for extinction and is considered to be one of the worst invasive species in the world.

Foxes are not related to wolves or domestic dogs. They shared a common ancestor called tomarctus, which is believed to have hardly resembled a dog, but more of a mustelid about 15-17 million years ago. The two species are unable to interbreed, and rumors of the existence of “doxes” (hybrids) have not been confirmed.

Vulpes vulpes is the most widespread species of fox. As a member of the order Carnivora, the red fox is an omnivore. It is primarily carnivorous, but can subsist for extended periods on roots and berries. The preferred prey of a red fox is rodents, rabbits, birds, and small ungulates. They will also eat fish, insects, and eggs when available.

Foxes are also preyed on by large predators such as bears, wolves, and felines. They are also hunted by humans for sport and pest control.

In a protected environment, a red fox can live up to 15 years. However, most don’t live past 5 in the wild due to starvation,predation, and disease.

Foxes are vocal animals, and use different types of sounds to communicate with each other. They employ a wide range of barks, shrieks, chirps, and warbles.

Cultural History

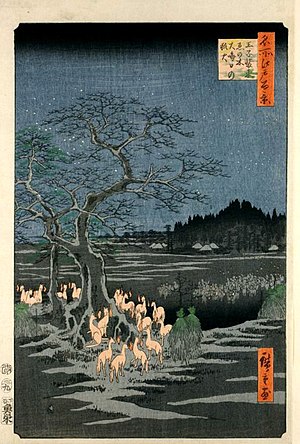

Pacific Asia Museum. Gathering of Foxes at Oji from the series “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” Ando Hiroshige (1797–1858)

Since the red fox is present in almost every continent, it is not surprising that it has appeared internationally in literature and art. In its relationship to humans and other animals, it is a nuisance. It can’t be tamed, it can’t be farmed, and it preys on small livestock when available. Since it is so adaptable, it can survive almost anywhere.

Its adaptability has been translated into “cunning” across cultures. The earliest record of a vulpine character comes from Aesop’s fables. Aesop, who was believed to be a slave during the 6th century BCE, employed the fox respectfully by depicting it as a character “too clever by half.” (Macdonald, 25).

During the 1100s, through generations of re-interpretations, the fox became synonymous with the Devil. The oldest known vulpine antagonist was introduced in

Ysengrimus, a poem written in the 1150s by an unknown author in the vicinity of France, Alsace, and Germany . This work is thought to be allegorical, although the historical context has not been confirmed.

Ysengrimus the tale of a noble everyman, represented as a wolf. Reynard the Fox is Isengrin’s corrupt and wily foil.

Book of Hours/ Livre d'heures/ Stundenbuch - Utrecht, Master of Catherine of Cleves, Lieven van Lathem (illuminators); Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum (MMW), Den Haag

Almost every European culture has a version of this tale. From Aesop’s “The Fox and the Crow” to Italo Galvino’s “Giovannuzza the Fox” (1956), this animal appears as a cunning, deceitful trickster.

“There is hardly a language in Europe in which the word ‘foxy’ is not synonymous with trickery and deceit.” (Macdonald, Running with the Fox).

These characteristics are artistic embellishments on the fox’

s natural behavior. Foxes are resourceful and well-adapted to many environments. Their small size allows them to hide from large predators and fit into tight places. Their natural agility and keen eyesight allow enable them to stalk and catch small prey. They have excellent hearing and can detect low frequency sounds.

Yuri Norstein. The Fox and the Hare. 1972.

In ancient Japan, the fox is roguish, but considerably less dastardly. The harvest god Inari is often depicted as a fox, ( or a dhole, a close relative common to the area). In many cities stone fox heads adorn public spaces.

Why a fox? Speculation suggests that after a harvest, mice and other rodents that eat the crops are revealed. Foxes are seen catching large number of them, and so the legend infers that the foxes protect the fields by eating the vermin that destroy it. This scenario features them as benevolent creatures as opposed to pests.

- Ohara Koson -“Kitsune.” Alphabestiary. May 11, 2011

- Koukan – Wall Scroll. N.d. Medieval. A fox dressed as a priest.

- Fanpop.com. Artist unknown. This subject made for a very awkward image search

- The Legend of Zorro – Aristocratic playboy Don Diego de la Vega becomes the masked vigilante “Zorro” (Spanish for “Fox”, named for his quickness and cunning). Created by Johnston McCulley, 1919. This character later inspired the well-loved DC character “Batman.”

- Thereocephalic characters and their “pure animal” counterparts. The gentleman is a fashion-conscious art student and the lady is a glamorous self-portrait.

The earliest known images of foxes in traditional artwork were found in East Asia. These sculptures are believed to have existed before the Medieval era, but have no specified date. Some examples include stone “Inari” fox sculptures in Japan, as well as wall scrolls and blockprints.

Inari - Japan: God of agriculture. David Gardiner Garcia. Sacred Destinations.

Foxes take many forms in ancient Japanese mythology. A reoccurring character in Japanese folklore is the “Kitsune” – a vixen that can take the form of a beautiful woman. She isn’t a malevolent creature, but her intentions are less than pure. She is also the inspiration of many works of fan art of questionable intent.

The foxes in early Japanese mythology are spirit animals. They only resemble the animal in appearance and behavior. Real foxes are not seen as divine beings, although they are sometimes affiliated.

Excerpts from observations

I observed the foxes at Northwest Trek in Eatonville, Washington. There are four foxes on exhibit, 3 males and 1 female. They were all captured in the wild. I didn’t know their biological genders at the time, so I gave them unisex names in order to keep track of them.

“Robin” is the smallest of the group. S/he has a sparse tail and grey hindquarters.

“Avery” is slightly larger than Robin and has a tuft of fur at the end of his/her tail.

“Blair” is the largest and most robust of the group. His/her coat is very thick and entirely red.

“Alex” is average height and very wiry. S/he has a mostly grey coat and fluffy tail.

When I was taking notes, I wanted to be sure that I included as much about the environment that I could. This includes the enclosure, plant life, and park visitors.

Week 1 – 4/12/12: West Bay Park

3:40 – Arrived at West Bay Park to observe the alleged red foxes. Knowing that these fellows prefer night hunting, I figured that I would most likely see them at this time.

3:50 – West Bay Park – Cold, clear skies, light breeze. 2 other people on the premises. Ducks or Frogs croaking. Gulls crying.

4:15 – Gulls crying, disturbance in the water, maybe a duck. Temperature drop. No sign of fox/es.

4:20 – Changed location – moved further south. Songbirds calling, frogs croaking. Cloud cover moving in.

4:35 – More bird activity across the bay. Ducks waking up.

4:50 – Walked around premises. No sign of fox. Temperature intolerable.

All 3 are now laying down at the edge of the enclosure. Their heads are turned in my direction.

12:00 – Avery gets up and moves to the other side behind a grove of trees. Blair stands up and stretches, starts walking, lies down facing the other direction. Robin was sitting with their back to me but has relocated.

12:15 – Avery and Robin have left the scene. Blair is still lying down. I’m going to check back in a few.

Interrupting hummingbird.

12:30 – Returned to exhibit. No fox in sight. Climate: sunny, clear skies, light breeze.

12:45 – No activity.

1:00 – Avery spotted sleeping in a sunny patch behind trees. A visiting photographer said that they tend to move around depending on where the sun is.

1:15 – No fox activity. Many visitors. Crows and ravens calling.

1:30 – Coyotes screaming. Foxes sleep through the commotion.

Week 5 – n.d.: Northwest Trek

2:15 – …..someone is yelling “A giraffe! A giraffe!” A particularly loud group of people have arrived. The air smells like an odd combination of coffee and marijuana. That musky smell I mentioned earlier? It’s from the foxes. My interpretation of foxes as art students was spot-on.

2:30 – I see another [fox]. It’s Avery. S/he has joined Blair in the sunny patch. His/her tail and coat are fuller now. The keeper has come by with the mice [food] and Alex has bolted across the enclosure. Here comes Robin. S/he is sniffing the ground around the tree. Their tail is very white and appears to be shedding. Blair has their eyes fixed on the caretaker. The others have left. Blair returns to the patch.

3:00 – Coyotes are barking. Their voices are high-pitched and not unlike Pomeranians.

3 Part Invention – Creative Writing

II. I am impressed by a raven’s vocal range and audio memory. I wonder, do they pick up sounds and play them back, or do they make them up? Do they compose and improvise?

I like to think of them as the earliest experimental acoustic composers.

Are they building sound collages from found materials? I suspect that their calls are some form of imitation. When one makes a guttural growl, I think that he might be mimicking a car engine. When another shrieks, maybe she heard the gates close.

Apparently crows and ravens can recognize faces. Can foxes do the same? When these fellows look up when I approach, do they see me as another animal or just another disturbance . Do I remind them of other animals they might be familiar with? Am I like a tall grouse, or an upright coyote? Am I threatening? Imposing? Majestic? Do they really care?

III.

My dear friend,

I was expecting this, but I didn’t know what to expect.

I came to you because I needed you. I sold all of my possessions for this. I told everyone I was leaving, and that they shouldn’t worry if I never came back. I would be with you – my sacred guardian, my vulpine angel.

I prayed for days and nights. I spent years learning how to see again. I thought I was ready for your earthly wisdom.

I needed you. I thought you would lead me to a better existence where all worldly vices failed. You were the one that could pull me from this abyss that swallowed everything I had once loved.

My divine vessel, herald from the next realm, where were you? We could have left this place together as mentor and pupil. We could have crossed bridges between now and yet to be, dark and light, man and animal, earthly and divine.

I came out here for this and as you can see, it’s been a thoroughly awkward encounter. We’ve been standing here a long time, and I can see that you’re eager to move on. I thought there was something between us, some unspoken understanding. Something bigger.

I apologize for putting you through with this. Seeing what you are, I should have guessed that you had more pressing matters on your agenda than me. I guess it comes to this. You go your way, I’ll go mine.

Works Cited

Taming the Wild: Animal Domestication Evan Ratliff March 2011. Web. 30 April 2012

Maddonald, David. Running with the Fox. New York: Facts on File 1987. Print.

Kistune: The Japanese Fox. Kitsune, Kumiho, Huli Jing, Fox. Fox Spirits in Asia, and Asian Fox Spirits in the West. N.d. Web. 30 April 2012.

Oparenko, Christina. Ukranian Folktales. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1996. Print.

Ranke, Kurt. Folktales of the World: Germany. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1996. Print.

Nature of the Beast: Japanese Paintings. Pacific Asia Museum. 2006. Web. 30 April 2012

Robinson, Christian. “Yuri Norstein.” Moss Covered Blog. 13 February 2010. Web. 30 April 2012

Alderton, David. Foxes, Wolves, and Wild Dogs of the World. New York: Facts on File. 1994. Print

Zorro: The Legend Through the Years. Zorrolegend.com.