Unless you’ve studied Mycology, Soil Science, or Ecology you likely haven’t learned much about fungi, let alone heard of mycorrhizae. When looking up at a towering Cedar, there usually aren’t any tell tale signs that there is a vast, underground network of interdependent organisms responsible for the great height of that tree. Alas, you look over and see some brightly colored blobs between two neighboring trees. It’s probably just some trash left behind by some careless teenagers. Oh wait, no.. they’re mushrooms! Strange and mystifying organisms, aren’t they? Well, these are just two forest inhabitants sharing the same soil space, real estate out here is tough, right?

There’s a lot more to the story.

The experienced mushroom forager has likely observed seasonal fruiting habits and habitats, noting the consistency of many fungal species growing near a specific set of trees. But even to the seasoned mycophile, (myco-fungus, phile-loving) these aboveground displays are only a visible indicator that there is an intimate connection below their feet.

So what are mycorrhizae?

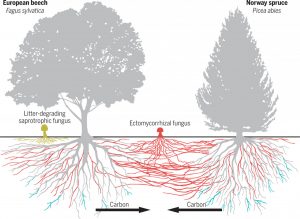

If you’re looking for the straightforward definition, mycorrhizae are a type of branched, tubular filaments (hyphae) of fungi that create various form relationships with higher plants. Myco or mýkēs meaning fungus or mushroom, and rhiza meaning root. Mycorrhizal fungi link the roots of at least two plants and occur in all major terrestrial ecosystems.

Symbiosis – The Perfect Union

Both the plants and fungi involved in mycorrhizal relationships are benefited, a perfect example of symbiosis. After the fungus has seduced the plant using hormones that alert the plant not to signal its defense mechanisms, it enters the plant root and the exchange begins. The vegetative growth of the fungus (mycelium) spans a much larger surface area than the plant roots can, optimizing the plant’s availability to necessary nutrients. Mycelia act as a big web, catching water and minerals from the soil which it transports into the plant roots along with its by-product Carbon. In return, the plant happily provides some of the sugars it produced during photosynthesis.

While nearly 90% of plants count on their fungal symbionts, only 10% of identified fungi are mycorrhizal (Lewis, 2016), a significant portion of macrofungi (ectomycorrhizal) and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi make up this group.

This network not only benefits the individuals who establish the relationship, but the entire forest. “Mother trees” can pass on nutrients to seedlings, and energy deficient neighbors, and dying trees can share their resources with their community via the mycorrhizal network (Simard, 2009). Plants can also warn each other about threats including toxins and predators. These connected pathways have been compared to the internet, sometimes called “The Wood Wide Web”.

Why is this important?

As the climate steadily changes, fungi are at risk and have began to migrate to more favorable environments. While fungi are not the sole organisms in partnership with plants, they will not flourish without their fungal friends. In a biodiversity report the U.S Department of Agriculture sums it up by saying “Without mycorrhizal fungi, the forest would not exist.” (“2012 Tongass Monitoring and Evaluation Report”, p. 2)

Resources:

Britannica, T. E. (2009, August 07). Mycorrhiza. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/mycorrhiza

Lewis, J. (2016). Mycorrhizal Fungi, Evolution and Diversification of. Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology, 94-99. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800049-6.00251-1

Simard, S. W., Beiler, K. J., Bingham, M. A., Deslippe, J. R., Philip, L. J., & Teste, F. P. (2012). Mycorrhizal networks: Mechanisms, ecology and modelling. Fungal Biology Reviews, 26(1), 39-60. doi:10.1016/j.fbr.2012.01.001

Simard, S. W. (2009). The foundational role of mycorrhizal networks in self-organization of interior Douglas-fir forests. Forest Ecology and Management, 258. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.05.001

2012 Tongass Monitoring and Evaluation Report. (2012). USDA. Retrieved from https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5419825.pdf.

January 26, 2019 at 12:50 pm

so

January 26, 2019 at 12:50 pm

good