Resurfacing from a deep blue free-dive in Miami, FL Credit:Roy F.

I grew up in a small coastal town that hugs the shores of Southern California, where life revolves around the ocean. I learned how to swim in the choppy waves before ever entering a swimming pool. So you can say the ocean has always been a part of my life. In 2017, I became a PADI certified free diver. As a free diver, the ocean is the place where I go to find silence, wonder, and serenity. I hold my breath, sometimes upwards of 1 minute and 30 seconds. While pulling myself beneath the surface, the depths constantly call my name, tantalizing me to come closer. Free-diving has greatly deepened my respect and awareness for life beneath the waves.

The seven seas cover 70% of the Earth’s surface and are the cornerstones of our life support system. They provide many essential ecosystem goods and services essential for the prosperity of humanity including:

- food

- medicinal products

- carbon storage

- roughly half of the oxygen we breath (Levin, et al.2008)

The Sea of Cortez, Baja California, Mexico Credit: Makenna Medrano

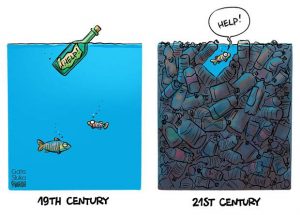

Despite their central importance to the human endeavor, oceans remains invisible to most of society. The disassociation to the wonders which lie under the waves has led to very serious threats, unprecedented in modern human history. Oceans are warming and acidifying, sea levels are rising, resources are being extracted faster than are being replenished, and the seas are becoming more and more polluted. (Levin, et al.2008)

And while I would love to touch on every aspect of threats to the ocean, this blog would quickly turn into a book.

Instead I am going to focus on one aspect which I feel strongest, plastic pollution, especially microplastics, and how they affect life under the sea and the potential hazards posed to humans.

But it’s not all doom and gloom, I will also share sustainable solutions to plastic pollution. Specifically, exploring my first hand in experience in Benin, West Africa where communities are working tirelessly to reduce their environmental impacts.

Microplastics: an insidious threat

Since the first fully synthetic plastic was invented in 1907, plastics have embedded their way into our everyday lives. Most humans have depended on plastic use as a cheap and extremely versatile product. For more information on the history of plastics click here .

As the global population continues to rise the demand for manufactured goods and packaging, to contain or protect food and goods has continued to increase. More than 30% of plastics are made into disposable items such as packaging, which are typically discarded within a year of manufacture. (Anderson, 2015) The associated throw-away culture has led to an escalating plastic waste management problem, and widespread accumulation of plastic debris in the natural environment.

A December 2014 study derived from six years of research by the 5 Gyres Institute estimated that 5.25 trillion plastic particles weighing some 269,000 tons are floating on the surface of the sea. (Eriksen, et al. 2014) . A different 2014 study even reported finding large quantities of microplastics frozen into Arctic ice. (Obbard, et al. 2014)

Small fragments of plastic (<5 mm diameter) known as “microplastics” have accumulated in the oceans through direct release of particles from cosmetics (also known as microbeads), release of fibers from washing machines, and most substantially from the fragmentation of larger items of plastic debris [Thompson et al., 2004; Barnes et al., 2009; Browne et al., 2011].

Image of plastic pieces found inside of a fish caught at sea Source: Spotmydive

Plastic never fully degrades, instead it breaks down into ever-smaller pieces due to sunlight exposure, oxidation, and the physical action of waves, currents, and grazing by fish and birds.

Human health impacts

As a free diver and spearfisher-woman, I can’t help but think about the potential health concerns posed on humans from consuming organisms that ingest plastic particles. Humans tend to worry about pesticides sprayed on their produce and the antibiotics pumped into the animal proteins they consume, so is it time to start worrying about the toxic chemicals that bind to plastics which marine animals we love to feast on, such as fish and oysters, consume?

This video delves into research being done to track the source of plastic being found in shellfish.

“When you eat clams and oysters, you’re eating plastics as well,” (Dudas, 2017)

The sorption of toxicants to plastic while traveling through the environment have led some researchers to claim that synthetic polymers in the ocean should be regarded as hazardous waste.(Rochman et al. 2013) The extent and rate of sorption greatly depends on the chemical, plastic type, as well as other variables, but plastic particles taken from the ocean have been found to contain pollutant concentrations orders of magnitude higher than the water from which they were collected. (Seltenrich, 2015)

Marine organisms consume plastics of various sizes starting at the lowest trophic levels of the food chain, the tiniest microplastics are small enough to be mistaken for food by zooplankton. (Cole M et. al, 2013) Research has shown that harmful and persistent organic chemicals can both bioaccumulate and biomagnify within organisms, causing the consumers to assume some of the chemical burden of their prey.

So if I am the predator, am I assuming the chemical burden of my prey?

Of the many U.S agencies, the EPA is starting to delve into the science to answer questions that revolve around marine plastics and human health. They are starting to consider key questions such as the extent of plastic pollutants transferring to organisms upon ingestion and the proportion of humans’ exposure to plastic chemical ingredients and environmental pollutants through seafood. Although these questions remain unanswered because, according to the Environmental Health Perspectives, “any study of human health effects will likely depend on the cooperation of a subject community where many types of seafood are heavily consumed.” But steps in the right direction are being taken, the EPA expects to award a new four-year marine debris research contract designed to gain a better understanding of plastics off the remote northwestern Hawaiian Islands. (Seltenrich, 2015)

Innovation: Solutions to plastic pollution

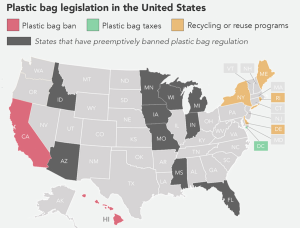

With a recent wave of awareness of the detriments of single use plastics on marine systems, there have been many efforts to reduce plastic pollution on a National and Global level. This has been achieved through voting and changes in legislation. Years of activism and campaigns proved successful for plastic bag ban campaigns in the U.S and worldwide.

Map of plastic bag legislation in the U.S. Credit:ReuseThisBag

Map of plastic bag bans and taxes around the world Credit:ReuseThisBag

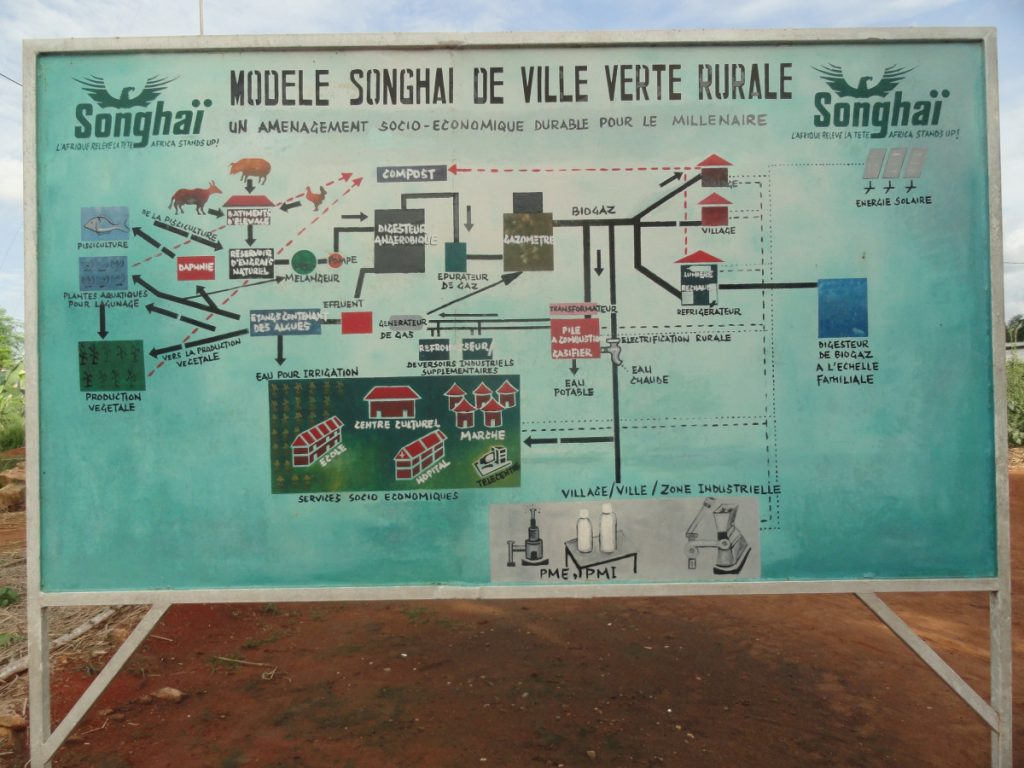

In 2014, I was fortunate to study abroad in Benin, West Africa where I learned about sustainability efforts of a small community named the Songhai Center. The center is a non-governmental organization with multiple bases throughout Africa dedicated to promoting sustainability through teaching and the implementation bio-production, bio-processing, bio-consumption, and bio-energy technologies. They choose to take advantage of the planets natural resources all while creating little to no waste. It is the efforts of communities such as Songhai that the rest of the world could learn valuable lessons from. If your are curious about who Songhai is and what they do visit: www.songhai.org.

A flow chart showing the production and use of zero waste energy in the Songhai Center, Benin Credit:Makenna Medrano

Post recycled plastic pellets being prepared to turn into plastic bottles for juice manufactured at the Songhai Center Credit: Makenna Medrano

The final product of juices manufactured and package into post recycled plastic ready for delivery. These bottles are encouraged to be returned and recycled again at the Songhai Center Credit: Makenna Medrano

Water filter made out of recycled plastic at the Songhai Center Credit: Makenna Medrano’

References:

Cole, M., Lindeque, P., Fileman, E., Halsband, C., Goodhead, R., Moger, J., & Galloway, T. S. (2013). Microplastic Ingestion by Zooplankton. Environmental Science & Technology,47(12), 6646-6655. doi:10.1021/es400663f

Eriksen M, Thiel M, Prindiville M and Kiessling T (2018)Microplastic: What Are the Solutions? Freshwater Microplastics, 10.1007/978-3-319-61615-5_13, (273-298)

Christensen, K. (2017, September 19). Guess What’s Showing Up In Our Shellfish? One Word: Plastics. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/09/19/551261222/guess-whats-showing-up-in-our-shellfish-one-word-plastics

Levin, S. A., & Lubchenco, J. (2008). Resilience, Robustness, and Marine Ecosystem-based Management. BioScience,58(1), 27-32. doi:10.1641/b580107

Obbard RWGlobal warming releases microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice.Earth’s Future2(6):315-3202014.; doi:10.1002/2014EF000240.

Seltenrich, N. (2015). New Link in the Food Chain? Marine Plastic Pollution and Seafood Safety. Environmental Health Perspectives,123(2). doi:10.1289/ehp.123-a34

Thompson, R. W., Sadri, S., Wong, Y. Q., Khitun, A. A., Baker, I., & Thompson, R. C. (2014, June 20). Global warming releases microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice.

Woodall, L. C., Sanchez-Vidal, A., Canals, M., Paterson, G. L., Coppock, R., Sleight, V., . . . Thompson, R. C. (2014). The deep sea is a major sink for microplastic debris. Royal Society Open Science,1(4), 140317-140317. doi:10.1098/rsos.140317