Natural History of Oysters

Life cycle and Reproduction

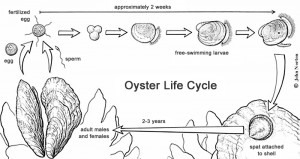

A oyster is born after an unfertilized egg comes into contact with a sperm. The egg then becomes fertilized and swims freely for approximately two weeks. During this time period the oyster develops cilia to allow water flow, an organ called velum that is responsible for moving and eating, and its shell. After two weeks the oyster develops a sort of foot that seeks to permanently attach to a surface. After the oyster attaches to a surface it is known as a spat. This spat settles, filters water, and grows. After about one to three years the oyster is an adult and is ready for human consumption.

In “perfect” conditions with ideal temperature, salinity, food, and other factors, an oyster can be sexually mature after six months; however they are usually sexually mature after a year. Oysters reproduce using external fertilization, where the female egg and male sperm are shot into the water and become an embryo outside of the body. Male oysters can release anywhere from hundreds of thousands to millions of sperm. Reproduction usually occurs during the summer when the water temperature is at least 75 degrees Fahrenheit.

Native and Cultivated Geographic Ranges

There are five species of oysters: the Atlantic, the Pacific, Kumamotos, Olympias, and Belons. Atlantic oysters are native to parts of Canada, the East Coast, and parts of the Gulf. Pacific oysters are native to the Pacific coast of Asia, they were introduced to US sometime during the 1900s and is the most farmed oyster in the Pacific Northwest. Kumamotos are native to Japan and was introduced to the US in the late 1940s. Olympia oysters are native to the Pacific Northwest, and Belons are a species of oysters native to Europe. Today oyster are cultivated in over 45 countries, but production is the highest in China, Korea, Japan, the US, and Japan.

Suitable Habitat

Oysters are typically found in estuaries, sounds, bays, and tidal creeks from brackish water (5 parts per thousand [ppt] salinity) to full strength seawater (35 ppt salinity). Oysters are also able to withstand wide variations in temperature, salinity, and concentrations sediments and oxygen. Although oysters can withstand various conditions, ecosystems with abnormally low salinity, high temperature, low amounts of dissolved oxygen, and incoming sediments can increase the risk of disease and a decrease in spawning.

Major Predators

According to M.F.K Fisher’s Consider the Oyster, oysters have eight predators. These predators include the starfish, a snail called a screw-borer, sponges, leeches, mussels, slipper shells, ducks and humans. Starfish have been known to wrap their arms around the oyster, crack open their shells, and suck out the body with their stomach-mouths. The screw-borer screws holes all over the oyster’s shell until it is penetrated and the body is eaten. Sponges attack oysters in a similar way; they will drill tiny tunnels throughout the oysters shells until the oyster becomes weak from trying to fill up the holes. The sponges then smothers and kills the oyster from the outside. Leeches and mussels can smother an oyster similarly to sponges, and will often times occupy the outside of their shells and take their food, leaving the oyster weak from competition. After severing the hinge of an oyster shell with a knife, humans tend to crack open the shell, slice through the abductor muscle and slurp right out of the half shell.

Parasites and Diseases

Oysters are prone to a fair amount of diseases and parasites. Many of the illnesses are contracted and effect the oyster during the larval stage. Oysters suffer from three known diseases: Dermo disease, MSX, and Roseovarius.

- Dermo disease is caused by a single-celled Protozoan parasite called Perkinsus marinus. This organism thrives in waters with temperatures above 25 degrees Celsius and a salinity over 12-15 ppt. Infected oysters usually exhibit a reduction in growth rate, poor condition, and reduced reproductive capacity, or even premature death.

- Multinucleated Sphere Unknown, or MSX disease, is caused by a single-celled Protozoan parasite called Haplosporidium nelsoni and mostly affects oysters native to the East Coast from mid-May to October. This organism thrives in water with temperatures above 20 degrees Celsius, and infection can be anywhere from mild to fatal in water with 15-20 ppts.

- Oyster Disease (ROD), previously known as Juvenile Oyster Disease (JOD), is caused by a marine proteobacterium called Roseovarius crassostrea. This bacteria affects hatchery-raised seed of eastern oysters, Crassostrea virginica, on the east coast of the U.S. from Maine to New York.

Nursery Propagation Methods

In a natural setting, fertilization happens after a female egg and male sperm are fused together outside of the body. Usually all oysters in a given area are spawning at the same time, but in hatcheries, spawnings are controlled through temperature to ensure a year-round supply. Oyster larvae grown in hatcheries go through the same growth stages as mentioned earlier. However, in the hatchery, the concentrated larvae are in large fiberglass tanks and must be supplied with suitable conditions and nutrients for growth. The oysters are fed phytoplankton and algae, some grown, some naturally-occurring.

Typical Aquaculture and Harvest Practices

A few aquaculture practices include the off-the-bottom method, and the on-the-bottom method. The off-the-bottom includes planting old, empty oyster shells in the intertidal zone and allowing the larvae to attach to them. The off-the-bottom method includes growing the oysters in cages, racks, or mesh bags. Harvesting from the on-the-bottom method is usually done by hand raking and picking or by dredges when intertidal beds are submerged. Oysters grown in trays or nets suspended from longlines are harvested from small boats.

Productivity of the Industry

Map showing areas of oyster production worldwide. (Source:FAO Fishery Statistics, 2006)

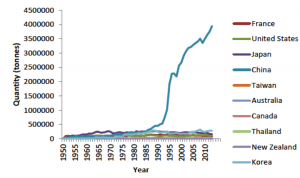

The quantity of oyster production in tonnes by country (Source: FAO 2014)

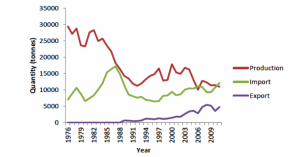

Production and trade of oysters in the United States (Source: FAO 2014)

Kumamoto oyster (Crassostrea sikamea) vs. native Olympia oyster (Ostrea lurida).

The Olympia oyster was pretty successful in the Puget Sound Area during the 19th century, but by 1890 the industry crashed due to pollution and over-harvesting. In an attempt to save the oyster industry, the Washington aquaculture industry began experimenting with Kumamoto oysters. The Kumamotos grew successfully, but because they come from such warm waters they do not spawn naturally in the colder waters of the Western coast of North America. In order to grow them, shellfish farms heat the water they are in to induce the spawn.

Written by Jahni Threatt. Edited by Chloe Landrieu Murphy

Cover Art by Jahni Threatt- Washington Oysters and Terroir, Group 10 logo