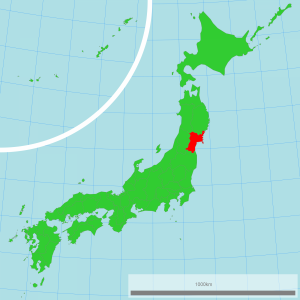

Native to the Miyagi region in Japan, Pacific oysters were originally grown off the coast of the northwest side of Japan. The Miyagi region has relatively cold waters compared to the Nagasaki region where Kumamotos are native (Jacobsen, 18), and is also quite exposed to the Ocean with fewer small inlets.

Pacific oysters grow well in cold and warm waters, and are grown along the West Coast of the United States all the way from Baja to Alaska (Jacobsen, 18). They prefer rich waters with larger algae and flourish along the West Coast, in France, and Australia (Jacobsen, 19). In Washington, Pacifics thrive in the intertidal zones of bays and inlets rich in a diverse population of algaes. Pacifics are much more adaptable to the West Coast climate than Kumamotos, which are also from Japan. Kumamotos originate from the Nagasaki region of Japan, which is full of small inlets and has much warmer waters.

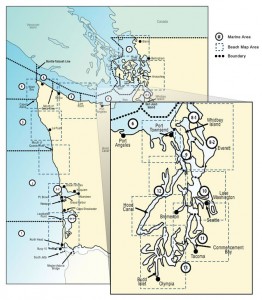

Even when growing in the warm waters of Nagasaki or Tomales Bay in California, Kumamotos still grow up to four times as slowly as Pacifics do (Jacobsen, 20). Olympia oysters grow at similar speeds to Kumamotos, and reach a similar size, which is much smaller than the average Pacific. Olympia oysters are native to the Western United States, and were once able to grow wild from British Columbia to San Francisco Bay (Jacobsen, 24). Olympias, however, are so sensitive to pollution and any change in their habitat that they are now only found in the South Puget Sound (Jacobsen, 24). Pacific oysters are arguably the most resilient oyster species and can adapt with incredible ease to new geographic habitats.

A pacific oyster grown in Tomales Bay will taste distinctly different than one grown in the Eld Inlet in Puget sound, or off of Vancouver Island, because the species is so versatile and adapts so well to change. The variety in geographic possibility of Pacific oyster growing gives us extensive opportunity to study the powerful impact of meroir upon a single species.

Leave a Reply