Natural History of Tea

(header photo: Dried Oolong Leaves by Lily H.)

written by Lily H.

Tea comes from the leaves of Camellia sinensis in the family Theaceae, and is a perennial evergreen shrub that can grow up to 5m. It is usually pruned to 1-2m for harvesting. The variety sinensis is native to the Chinese province of Yunnan. Its leaves are small and narrow and used to produce green and black teas. The variety assamica is less hardy with larger, droopy, leathery leaves that are used to produce Assam black teas. It is the native variety found in India. (Kew) C. sinensis produces fragrant white flowers about 4cm in diameter with 5 petals that bloom from March to May. The plant is not self-fertile and must be pollinated by bees. (PFAF; BioNet) Many commercial growers propagate tea through cuttings in order to improve quality of taste and keep genetic consistency. Growing from seed takes longer and does not ensure consistency. After 12-15 months, a successfully propagated cutting will grow roots and after another 12-15 months is ready to be harvested for the first time, a total of about 3-4 years. (Masionneuve)

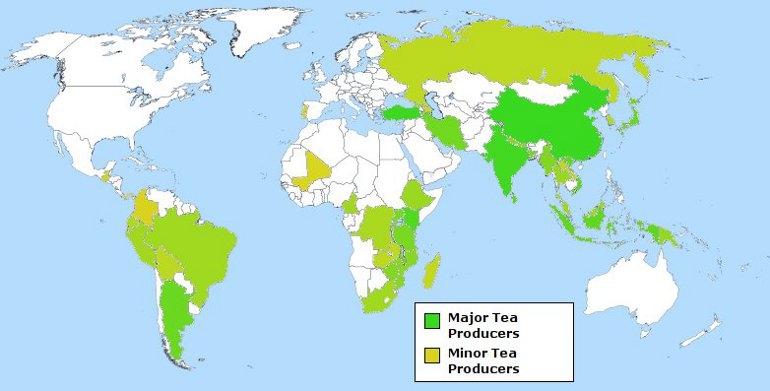

Tea is grown within the tropics and subtropics, between the latitudes 41◦N and 16◦S. (Hazarika et al., 268) The plants experience a wide range of climatic conditions with average annual temperatures ranging from 14 to 27°C, and annual precipitation of 70 to 310cm. It tolerates temperatures down to between -5 and -10°c and prefers a wet summer and a cool dry winter. (PFAF) It grows at altitudes up to 2100m, with the higher elevations producing higher quality teas. Misty, mountainous regions, such as the foothills of the Himalayas, are prime locations for growing tea.

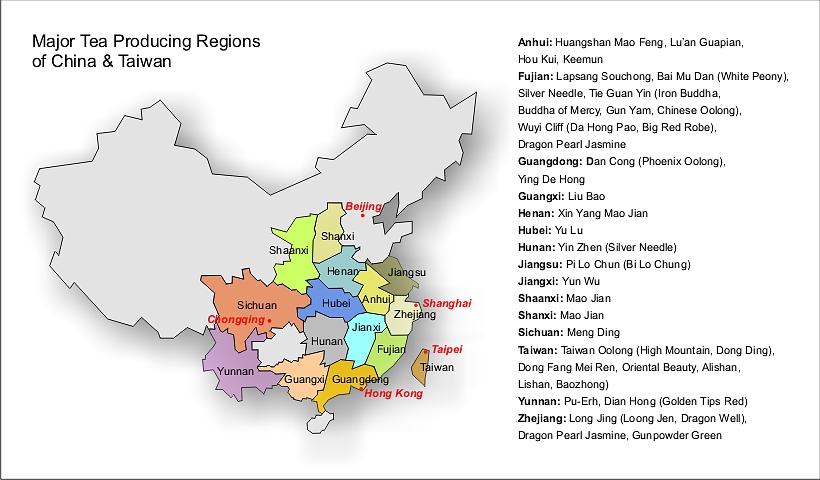

Tea grows in many countries throughout the world but China and India are the words largest producers.

C. sinensis is susceptible to a variety of different diseases which pose problems, especially in monocultured environments.

| Disease | Effect on Tea Plant |

| Algal Leaf Spot | The alga produces microscopic, rust-colored, spore-like bodies on the surface of the leaf spots, giving them a reddish tinge. Most algal spots develop on the upper leaf surface and do not harm the plant. |

| Brown Blight, Grey Blight | When young twigs of susceptible cultivars are cut and used to root new plants, latent mycelium in the leaf tissue may start to invade nearby cells to form brown spots, and this may lead to death of leaves and twigs. Rain splash transports the spores from one plant or site of infection to another. |

| Blister Blight | Blister blight is the most serious disease affecting shoots of tea and is capable of causing enormous crop loss. Following release of the fungal spores, the blister becomes white and velvety. Subsequently the blister turns brown, and young infected stems become bent and distorted and may break off or die. |

| Horse Hair Blight | Black fungal threads resembling horse hair are attached to upper branches and twigs by small brown discs. The fungus penetrates and infects the twigs from the discs and produces volatile substances that cause rapid leaf drop. It can spread to healthy twigs by extending its hair-like threads. |

| Twig Dieback, Stem Canker | As the disease spreads into the shoots, they become dry and die. The entire branch can die from the tip downward. Dying branches often have cankers— shallow, slowly spreading lesions surrounded by a thick area of bark. The fungus usually requires wounded plant tissue to gain entry and initiate infection. |

(Keith et al.)

Over 1000 species of arthropods are associated with tea cultivation. All parts of the plant are fed upon by at least one pest species which can result in yield and revenue losses costing hundreds of thousands of dollars. (Hazarika et al., 268)

| Common Pests | Effect on Tea Plant |

| Mirids | Nymphs and adults suck cell sap from tender stems, young leaves, and buds, forming reddish brown circular feeding punctures In severe infestations, the punctures curl upward and desiccate. Initiation of new shoots is prevented due to the death of the stem and may result in total loss of the crop. |

| Tea tortricids | A female lays eggs on the undersurface of young tea leaves from neonates emerge and disperse individually to construct leaf-webs for feeding on the growing leaves and shoots . |

| Shot Hole Borer | The newly emerged females construct galleries in stems 6.35 to 19.05 mm thick and cultivate the ambrosia fungus, Monacrosporium ambrosium Gadd & Loos, for raising mycetophagous larvae. This species has expanded its range by establishing in the high-altitude regions, possibly because of a rise in temperature due to global warming. |

| Mites | As a group, mites are persistent and the most serious pests of tea in almost all tea producing countries. Red Spider Mites lacerate cells, turning mature leaves reddish brown and result in crop losses up to 17-46%. High temperatures, dry conditions, and the absence of shade are conducive to outbreak of this pest. The Kanzawa spider mite also scars leaves and moves from one part of the tea plant to another and can migrate from the tea plant to another host. |

(Hazarika et al., 268-270)

While climate, altitude, geography, cultivation methods, and surrounding bio-matter all influence the presence of pests and diseases in a tea ecosystem, their management is a large issue in itself. To defend the tea crop against pests, organosynthetic pesticides are commonly applied, however, application is a burden to planters as well as to the environment. (Hazarika et al., 268) With the demand for contaminate free tea and sustainable products, tea cultivation must look toward Integrated Pest Management. Some of these management strategies include adjusting the pruning cycle to occur every two to six years, shade trees to alter microclimate and provide habitat for pest eliminating animals, and soil fertility management . (Hazarika et al., 271-273)

The soil tea grows in should ideally be a well draining, sandy clay loam with a pH between 4.5 and 7.3. Monoculture contributes to the depletion of nutrients such as phosphorus, nitrogen, and potassium in the soil that helps the plants grow. (Saha et. al., 34) Fortunately, studies have shown that inter-cropping with green crops such as Guatemala, Citronella, Mimosa and Calopogonium helps rehabilitate the soil by lowering the acidity and replenishing nutrients. (Saha et. al., 34; 38)

All of tea’s flavor comes from the leaves. Different harvest seasons, called flushes result in different qualities of teas. Depending on climate, some regions have more flushes in a year. For a tea like Darjeeling, the first and second flushes occur mid-March to mid-April to May and are highly prized and highly priced. The monsoon flush occurs from June to August and autumn flush from September to November . The leaf quality has degraded after the rains, meaning lower prices are paid for these flushes. Tea is generally not harvested in the winter months, though some areas are able harvest year round. (Besky, 12) For harvesting methods, some places such as Darjeeling put special emphasis on the “two leaves and a bud” and hand picking, while others often use machinery take a few inches off the top of the plants. (Besky, 8) After being picked and taken to the factory, the leaves go through the processes of withering, oxidation, rolling, and drying. (Besky, 9;11) To get different teas such as green or black the same kind of leaf is used, but the time of oxidation changes. The amount of time the leaves are exposed to air changes the style of tea and therefore the flavor – green has little to no oxidization, while black has been fully oxidized, and oolongs range in between. (Besky, 9;11)