Making Toast

Making Toast

Making toast is gathering up fabric, searching for “sewable” ideas, conjuring up images of the large-scale domestic space sculptures of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, and all the while craving hot buttered toasted bread. Visualized text from Nigel Slater’s Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger and thinking of ways to represent those visions in fabric made the adjective “burned” problematic. Slater’s recollection of his mother’s practice of burning toast kept me from moving forward with the project. But then, while listening to Edmund De Wall’s “Sunday Sermon” Tact on the online site of the U.K.’s The School of Life (http://www.theschooloflife.com/library/videos/edmund-de-waal-on-tact/), I realized that visualizing text is my representation and if fire and fabric just did not go together for me, then so be it.

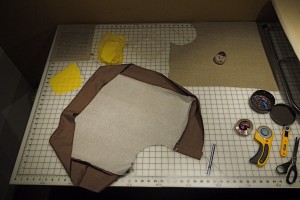

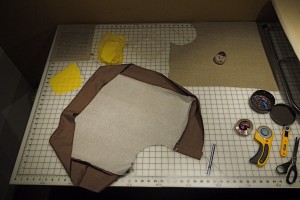

I have a domestic space devoted to sewing projects; the tiny room includes a closet with a fabric collection. All attempts to keep the fabric collection sorted by color and texture have failed, but I was able to find a nice “toasty” bolt of fabric. I have plenty of notions collected after years and years of sewing projects, “ah, that bundle of soft raw wool will work well as the “doughy cushion of white bread” that Slater referred to.

by color and texture have failed, but I was able to find a nice “toasty” bolt of fabric. I have plenty of notions collected after years and years of sewing projects, “ah, that bundle of soft raw wool will work well as the “doughy cushion of white bread” that Slater referred to.

In my effort to weasel out of re-typing the text of Toast for the project, a virtual “light bulb” of the mind blinked on, “this iMac might have speech typing”, and so it did. After figuring out the system, dictated text magically appeared on the screen. The next step was to print the text on fabric, which required a special process of preparing cloth to move through a printer. Of course the oversized piece of toast fabric would not fit the printer, so an 8 ½ by 11 inch piece of the fabric was cut—the problem of fixing it to the larger piece of fabric would have to be solved later.

As separate pieces of cotton, linen, thread, and wool became united, the boxy object resembled a pillow more than toast, but cutting away a bite to expose the “doughy cushion” that lies inside the crust offered a suspension of belief that just might work. The project moves on to butter. After a futile attempt to sew yellow rip stop nylon into a block of butter in a shape imagined to be 1960s British butter, I tossed the construction aside and sewed a rectangular stick of butter that looked more realistic. Slater writes “I am nine now and have never seen butter without black bits in it,” but since I have tempered the image of burned toast, my bits in the butter will be brown—stitch, stitch, French knot here, French knot there. I need a butter dish. I need a plate for the toast. Come together visualization of toast!

construction no.3

Construction no. 3

The inspiration for this construction comes from visualizing text in Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life (Hanh & Cheung 2011). The authors are centered on the Buddhist practice of mindfulness as “a guiding light that already exists inside every one of us,” (7) “a way of living that has been practiced over twenty-six hundred years by millions of people to help them transform their suffering into peace and joy” (34). The authors suggest a simple exercise that is particularly suited to living in the Pacific Northwest. Their “Apple Meditation” exercise calls for mindfulness applied to eating an apple. According to the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA), Washington accounts for 60% of US apple production (http://agr.wa.gov/AgInWa/). And serendipitously, the WSDA site offers a culinary agritourism Itinerary called .

So, lots of apples to taste, but the question raised by Hanh & Cheung is, “Are you Really Appreciating the Apple?” The text in construction no. 3 offers the steps to really appreciating the act of eating an apple. The apple is such a luscious fruit: color, crispness, sweetness and the promise of good health if one indulges every day is irresistible. Good thing, since we have so many wonderful apples available to us, and mostly at reasonable cost. When I was living in Japan for a time, apples were so expensive that it was never appropriate to munch a whole apple—no, in Japan, the practice is that an apple is cut into several pieces and the family group each takes one section as a dessert at the end of meal.

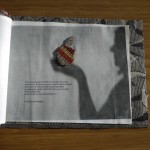

Last week I had the notion that a shadow image of myself would be a good starting point for the construction of images that might represent the steps of eating an apple with a sense of mindfulness and appreciation. Students in my critique group took this on: a light source in a darkened room projected my profile on a wall, the shadow was traced on paper accordingly—but the image was large and not crisp enough. Chantay, the eternal photographer that she is, offered to take a picture of my shadow and send it to me—digital ready. Perfect. The next weekend, a Portland friend stopped by after attending a workshop on fabric arts held in Port Townsend. She walked me through the process of making fabric rigid enough to go through a standard home printer. The idea emerged to use that technique to make pages for each step of savoring an apple. Making the pages took hours of PhotoShopping, experimental printing on paper, and playing with sizing. Then it was time to use the fabric sheets and six pages of shadow images and text were printed. The favored part of this construction was designing the tiny fabric apples secured to each page. My fabric scrap basket offered a profusion of possibilities—I started with leather and that remains my favorite—so smooth and rigid.

FINDING THE RHYTHM OF OUR WORK

May 2, 2013, 3:10 pm

Filed under:

Thoughts A couple of weeks ago while reading Savor: Mindful Eating, Mindful Life (Hanh & Cheung 2011) I came across the authors’ contention that there is a net of general everyday, moment-to-moment mindfulness. They referred to mindfulness as the rhythm of mindful living. At the same time, I was thinking about how the momentum of work is sustained, an especially vital concern when involved in a learning situation where there are few external controls coupled with all the distractions of modern life. I recommended writing out a schedule of activities so that a momentum of self-directed reminders is established: “every morning at 10:00 I will write in my journal,” or, “every Tuesday I go on a photo shoot, rain or shine,” or, Tuesday and Thursday evenings are devoted to journal writing.” But how is such a practice established in life? In the same week, a conversation with Crystal about the book You Are Your Child’s First Teacher (Dancy 2012) came up with the answer: we learn such patterns early in life, at home. Dancy’s chapter, “Rhythm in Home Life” presents the case that “children’s—and our own—life” can be simplified on four levels: “environment, rhythm, schedules, and filtering…” Adults influence work patterns that lead to internal self-direction by creating weekly rhythms of daily home tasks. As a Waldorf practitioner, Dancy quotes Rudolph Steiner (b.1861 d. 1925) the founder of Waldorf pedagogy, “Chaos prevails. But man must give birth again to rhythm out of his innermost being, his own initiative.”

construction no. 2

Adventures in Lighting

Construction no.2 is fitted with a tiny spotlight that shines on a set of beans made important in the essay “Beans and Me” by Jeremy Jackson from Alone in the Kitchen With an Eggplant: Confessions of Cooking for One and Dining Alone (ed. Ferrari-Adler 2008). In the essay’s story, the author imagines an interaction among anthropomorphized pinto, lentil, black bean, and black-eyed pea—the latter bean is left out of the limelight in an imagined scene.

Constructing the scene required the coordination of box size and intensity of light for the spotlight. There is, I discovered, a relationship between object and light that relates to the “inverse square law,” that is, that light falls off, inversely, with the square of the distance. This “law” came to my attention after an adventure into Radio Shack for the electrical materials to create a spotlight for a very tiny space. Radio Shack and electronics go together and I assumed that the local mall retailer and its staff would guide my adventure. Not so. After showing my box and quest to light it to who seemed to be the “manager,” she directed me toward a confusion of drawers with all sorts of wires, lights and other paraphernalia. As she stepped away from me, she smugly said she had no idea how any of those elements worked together. Well, how about the other teen aged employees? The young man shyly smiled with an absent look on his face, and the young woman was “very busy” at the moment, but she dropped the hint that the tiny lights with their mysterious wires need to be connected to a battery source. Of course I ought to know about the wonderful world of electronics, but at the moment any schooling on the subject was dim. I messed around those drawers for more than a half hour with excursions to the battery section of the store attempting to match up lamps with battery holders with battery voltages. I settled on a 6 volts mini lamp (a tiny light bulb with wiring) and a cool little plastic box with on/off switch that holds 4 “AA” batteries, each 1.5 volts to equal a corresponding 6 volts for the lamp. I took the pile of items to the busy young woman and she offered a “this should work” assessment. I didn’t spend much money but the self-education was priceless. I’ve always been fond of Jean Piaget’s premise that “to understand is to invent,” and here I had the chance to “invent” a connection of materials that would potentially create a spotlight for my box construction. Although my efforts of invention compare to a very elementary understanding of electronics, I experienced a sense of fulfillment as I left the store, clutching my Radio Shack parcel. But the lack of staff help made me wonder about the health of this retailer. A New York Times web search came up with the news that Radio Shack is in turmoil; last fall its chief executive stepped down following a 21 million dollar loss despite the retailer’s shift toward the smartphone market. The Internet is surely a wicked competitor, but I bemoaned the fact that others will be denied the chance to mess around a drawer of paraphernalia in a brick and mortar “store” as I did and “invent” an electronic connection. A tutorial on electric circuits like this one from Red River College offers post invention reflection: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3XS4lAxvrc

There was elementary thrill in connecting wires and seeing the little light blink on. I drilled a hole in back of the box to thread the wires through, glued the beans in place, and added call outs for the beans printed on vellum. But, oh my, here is where the inverse square law came into play. The tiny light was diffused across the bottom of the box and hardly spotlighted the trio of beans. I contemplated, “spotlight, spotlight,” then google imaged the term. Right, they have a lens tube that directs the light, limiting diffusion. I sawed off the end of a common pen top to create a black tube, fitted it with electrical tape and, well, see the spotlight effect?

construction no. 1

Yoshimoto’s Kitchen

The words that inspired this project’s first model construction to represent text are from Banana Yoshimoto’s book, Kitchen (1988):

The place I like best in the world is the kitchen. No matter where it is, no matter what kind, if it’s a kitchen, if it’s a place where they make food, it’s fine with me. Ideally it should be well broken in. Lots of tea towels, dry and immaculate. White tile catching the light (ting! ting!) (3).

The most captivating aspect in pre-production was the anticipation of sewing up tiny tea towels. I went to Canvas Works in downtown Olympia (http://canvasworks.net/) to find pure linen. The owner led me to the bolts of linen; I sheepishly disclosed that I was making an art project that required tiny linen towels (I presupposed from Yoshimoto’s text that the fabric of the tea towels was linen, and in fact, when I visualized the text saw the word “linen” associated with towels even though that precise word does not appear). The owner was surprisingly interested and became fully involved in helping me select the exact linen weight and color. Sewing the tea towels was the last step in the production of the piece. The first step involved inventorying the wooden boxes that I own. A cedar box made its way into my hands and I suddenly pictured how it could be re-fashioned to resemble a kitchen counter space and backsplash. In between those first and last steps I made my way to ReStore (http://www.spshabitat.org/restore/) to pick out white tile—as in “White tile catching the light…” Their inventory of tile was not as great as I remembered it to be, but I found a small box of assorted white tiles and chose two styles—my bag of about 40 tiles came to $1.60.

Next, I assembled all the parts, not making the mistake of gluing at that point. I cut the bottom of the cedar box in two with a Dremel jigsaw to form a “counter,” then sized things up to figure out where the text might go. I spent a good deal of time with an alphabet rolling stamp (http://img0.etsystatic.com/000/0/6261595/il_570xN.269250752.jpg), but this proved to be too inaccurate and annoying, so I switched to computer generated printing. Selecting the paper also proved to be time consuming, trying out different kinds of paper and fonts. An image from a Japanese calendar coordinated with the white tiles best and gave a nod to Yoshimoto’s heritage.

Glue the tiles—wait—grout the tiles (which proved to be very tedious and messy)—wait—glue the image with text—wait—glue the shelf—wait, tape the little pile of towels onto the counter—done.

Everybody lives somewhere

April 8, 2013, 5:46 pm

Filed under:

Thoughts  Whether one has a structure with four walls and all the amenities that go with one’s interpretation of the “good life,” or an open itinerant version of “home,” it all amounts to living somewhere, and we can picture that place in our minds.

Whether one has a structure with four walls and all the amenities that go with one’s interpretation of the “good life,” or an open itinerant version of “home,” it all amounts to living somewhere, and we can picture that place in our minds.

The White Tower by Worapong Manupipatpong

by color and texture have failed, but I was able to find a nice “toasty” bolt of fabric. I have plenty of notions collected after years and years of sewing projects, “ah, that bundle of soft raw wool will work well as the “doughy cushion of white bread” that Slater referred to.

by color and texture have failed, but I was able to find a nice “toasty” bolt of fabric. I have plenty of notions collected after years and years of sewing projects, “ah, that bundle of soft raw wool will work well as the “doughy cushion of white bread” that Slater referred to.