Introduction:

Peregrine Falcons are a widespread bird of prey. They are a large falcon that experiences sexual dimorphism in size. An average body size is 13-23 in. and a weight of 0.7-3.3 lb. Both females and males have similar plumage of a dark head, white underparts and a blue/gray/black back. Previously an endangered species, the Peregrine Falcon has made a remarkable recovery since widespread pesticide bans.

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

Genus: Falco

Species: Falco peregrinus

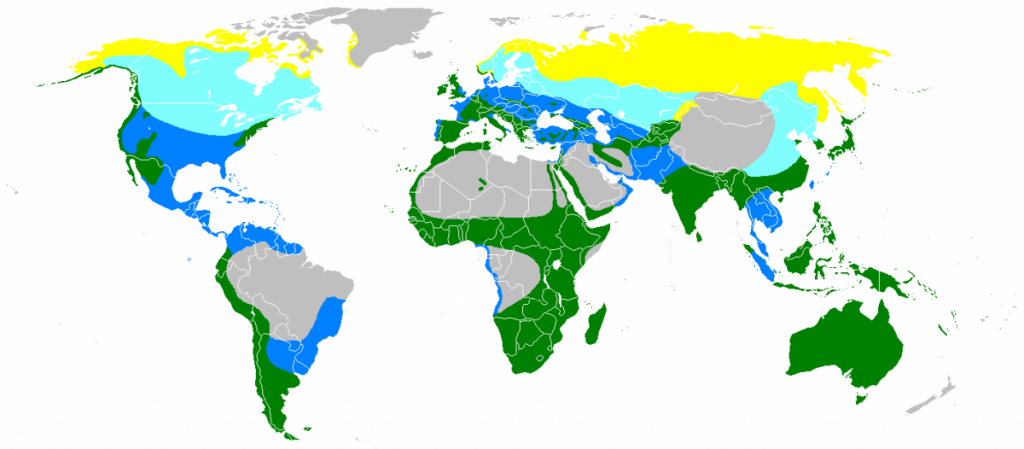

The Peregrine Falcon is widely distributed, existing on all continents except for Antarctica, and absent only from Oceanic islands, the Sahara, and the Amazon (White, 2002). Populations worldwide were diminished due to synthetic organic chemicals, but populations have been progressively rising. They have become a top predator in many ecosystems in the United States specifically (Stevens, et al. 2009).

There are 19 recognized subspecies of Peregrine falcons.

In Washington, the subspecies Falco peregrinus pealei is a year-round resident. Its territory is northwards from the Puget Sound, up the coast of British Columbia and the Gulf of Alaska, and to the eastern coast of Russia. The subspecies Falco peregrinus anatum may also be seen in the Pacific Northwest, but is mainly found in the Rocky Mountains.

Peregrine Falcons reside in a diverse number of habitats due to their widespread populations. They rely primarily on cliffs for nesting sites, whether natural or non-natural (Wakamiya, et al. 2009) They can often be seen in coastal areas and large cities, where they make use of tall buildings in lieu of their preferred cliffs (White, 2002). Peregrines can have large home ranges, usually in canyons or topographically complex terrains (Stevens, et al. 2009).

Peregrine Falcons have a wide variety of possible food sources due to their global abundance. They can be selective or generalist predators depending on the environment they reside in. They have shown to prefer medium-sized waterfowl, pigeons and doves, songbirds and shorebirds (Dawson, et al. 2011). City and urban dwelling Peregrines rely on a diet of mostly pigeons, doves, and other small passerines (White, 2002). Coastal residents rely less on songbirds, and more on waterfowl. Breeding pairs who had more waterfowl in their diet have shown to have better reproductive success (Dawson, et al. 2011). Peregrines will also hunt for small mammals, wasps, bats, and reptiles (Stevens, et al. 2009).

Peregrine Falcon Alarm Call in Washington State

Sound by Taylor Brooks on xeno-cantho

Peregrine Falcon flight call from Brazil

Sound by Luiz C Silva on xeno-cantho

Peregrine Falcons are the fastest member of the animal kingdom, they can reach speeds of over 200 mph while attempting their hunting stoop. They will sit on a perch and wait for a chance to dive for their prey. They generally catch their prey mid-dive during these stoops, preferring aerial hunting rather than catching prey on the ground. They are active hunters 24 hours a day, but tend to hunt most around dawn and dusk (Rejt, et al. 2001).

Peregrines generally begin to breed the second year they return to a nesting site (Wakamiya, et al. 2009). They are sexually mature at 1-3 years of age. Populations are believed to be regulated by the number of nesting sites in an area due to their highly territorial nature (Wakamiya, et al. 2009). Breeding pairs mate for life and return to the same nesting spot every year. Courtship includes the male passing food to the female mid-air while she catches it upside down.

Migration occurs in populations that breed in Arctic regions, populations in mild winter climates tend to not migrate or migrate short distances (White, 2002).

Peregrine Falcons are prized birds in falconry due to their hunting ability and train-ability. (White 2002).

Altwegg, R., Jenkins, A., & Abadi, F. (2014). Nestboxes and immigration drive the growth of an urban Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus population. Ibis, 156(1), 107-115.

Anctil, A., Franke, A., & Bêty, J. (2014). Heavy rainfall increases nestling mortality of an arctic top predator: experimental evidence and long-term trend in peregrine falcons. Oecologia, 174(3), 1033-1043.

Banks, A. N., Crick, H. Q., Coombes, R., Benn, S., Ratcliffe, D. A., & Humphreys, E. M. (2010). The breeding status of Peregrine Falcons Falco peregrinus in the UK and Isle of Man in 2002. Bird Study, 57(4), 421-436.

Brambilla, M., Rubolini, D., & Guidali, F. (2004). Rock climbing and raven Corvus corax occurrence depress breeding success of cliff-nesting peregrines Falco peregrinus. Ardeola, 51(2), 425-430.

Bruggeman, J. E., Swem, T., Andersen, D. E., Kennedy, P. L., & Nigro, D. (2016). Multi‐season occupancy models identify biotic and abiotic factors influencing a recovering Arctic Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus tundrius population. Ibis, 158(1), 61-74.

CRAIG, G. R. (1997). Wide ranging by nesting Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) determined by radiotelemetry. J. Raptor Res, 31(4), 333-338.

Dawson, R. D., Mossop, D. H., & Boukall, B. (2011). Prey use and selection in relation to reproduction by Peregrine Falcons breeding along the Yukon River, Canada. Journal of Raptor Research, 45(1), 27-38.

Dennhardt, A. J., & Wakamiya, S. M. (2013). Effective dispersal of Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) in the midwest, USA. Journal of Raptor Research, 47(3), 262-271.

Ponitz, B., Schmitz, A., Fischer, D., Bleckmann, H., & Brücker, C. (2014). Diving-flight aerodynamics of a peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). PLoS One, 9(2), e86506.

Rejt, Ł. (2001). Feeding activity and seasonal changes in prey composition of urban Peregrine Falcons Falco peregrinus. Acta Ornithologica, 36(2), 165-170.

Shobrak, M. Y. (2015). Trapping of Saker Falcon Falco cherrug and Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus in Saudi Arabia: implications for biodiversity conservation. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 22(4), 491-502.

Stevens, L. E., Brown, B. T., & Rowell, K. (2009). Foraging ecology of peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) along the Colorado River, Grand Canyon, Arizona. The Southwestern Naturalist, 54(3), 284-300.

Wakamiya, S. M., & Roy, C. L. (2009). Use of monitoring data and population viability analysis to inform reintroduction decisions: Peregrine falcons in the Midwestern United States. Biological Conservation, 142(8), 1767-1776

Watts, B. D., Clark, K. E., Koppie, C. A., Therres, G. D., Byrd, M. A., & Bennett, K. A. (2015). Establishment and growth of the Peregrine Falcon breeding population within the mid-Atlantic coastal plain. Journal of Raptor Research, 49(4), 359-367.

White, C. M., N. J. Clum, T. J. Cade, and W. G. Hunt (2002). Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.660

White, C. M., Sonsthagen, S. A., Sage, G. K., Anderson, C., & Talbot, S. L. (2013). Genetic relationships among some subspecies of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus L.), inferred from mitochondrial DNA control-region sequences. The Auk, 130(1), 78-87.

The Peregrine Falcon was listed as an endangered species in 1970, and in 1975 the US Fish and Wildlife department appointed an Eastern Peregrine Falcon Recovery Team to develop a recovery plan (Watts, et al. 2015). One key component of many Peregrine recovery plans is captive-breeding, the releasing of captive-reared falcons to develop populations. Falcons have been released and given nesting sites in urban areas at the top of buildings and water-towers, man-made nesting towers in rural areas, and natural cliff sites (Watts, et al. 2015). Nestboxes have also shown to have positive effects on peregrine populations (Altwegg, et al. 2014).

Widespread eradication of DDT use has allowed Peregrine Falcon populations to rise significantly. Reintroduction strategies in urban areas have been successful in increasing breeding pairs in cities, but have shown challenges in cliff areas where there is the risk of predation of young peregrines. (Wakamiya, et al. 2009). They have been thriving in urban areas where prey such as pigeons are abundant and buildings can act as surrogates for cliffs (Altwegg, et al. 2014). In these areas they are more at risk to human-influenced mortality, such as building and electrical wire collisions.

Peregrine Falcons are now listed as a species of Least Concern with a stable population by the US Fish & Wildlife service.

Richey Mariotte is a student in Birds: Inside and Out.

Leave a Reply