“Number of Teeth

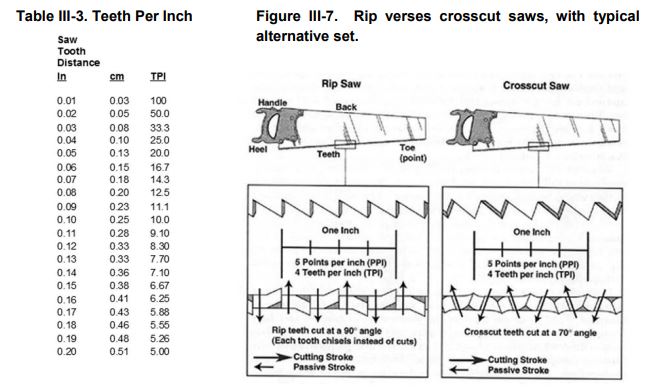

In general, blades with more teeth yield a smoother cut, and blades with fewer teeth remove material faster. A 10″ blade designed for ripping lumber, for example, usually has as few as 24 teeth and is designed to quickly remove material along the length of the grain. A rip blade isn’t designed to yield a mirror-smooth cut, but a good rip blade will move through hardwood with little effort and leave a clean cut with minimal scoring.

A crosscut blade, on the other hand, is designed to produce a smooth cut across the grain of the wood, without splintering or tearing. This type of blade will usually have 60 to 80 teeth, and the higher tooth count means that each tooth has to remove less material. A crosscut blade makes many more individual cuts as it moves through the stock than a ripping blade and, as a result, requires a slower feed rate. The result is a cleaner cut on edges and a smoother cut surface. With a top-quality crosscut blade, the cut surface will appear polished.

Gullet

The gullet is the space in front of each tooth to allow for chip removal. In a ripping operation, the feed rate is faster and the chip size is bigger, so the gullet needs to be deep enough for the large amount of material it has to handle. In a crosscutting blade, the chips are smaller and fewer per tooth, so the gullet is much smaller. The gullets on some crosscutting blades also are purposely sized small to inhibit a too-fast feed rate, which can be a problem especially on radial-arm and sliding miter saws. The gullets of a combination blade are designed to handle both ripping and crosscutting. The large gullets between the groups of teeth help clear out the larger amounts of material generated in ripping. The smaller gullets between the grouped teeth inhibit a too-fast feed rate in crosscutting.

https://www.rockler.com/how-to/blades-101/

======

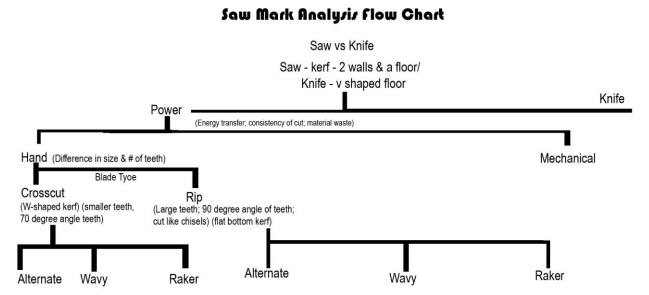

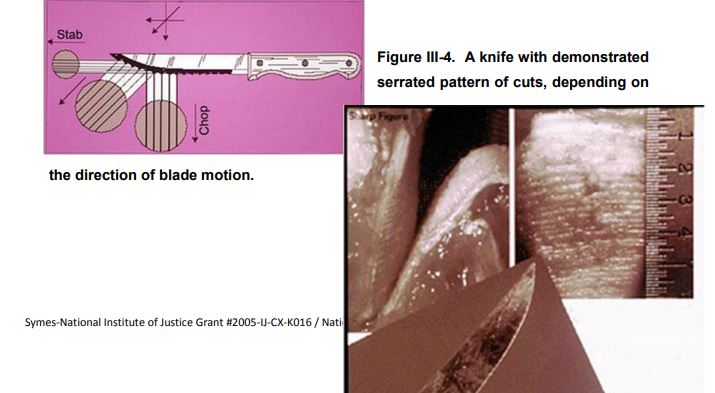

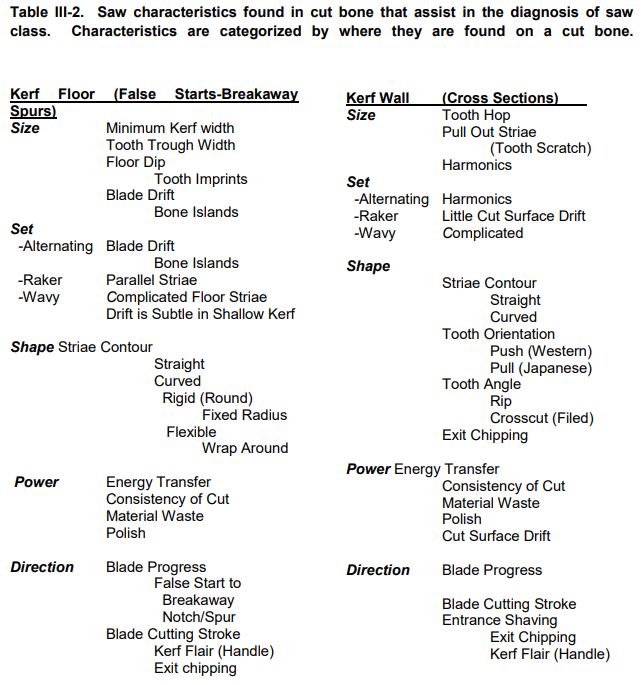

“Principles of Cutting Action

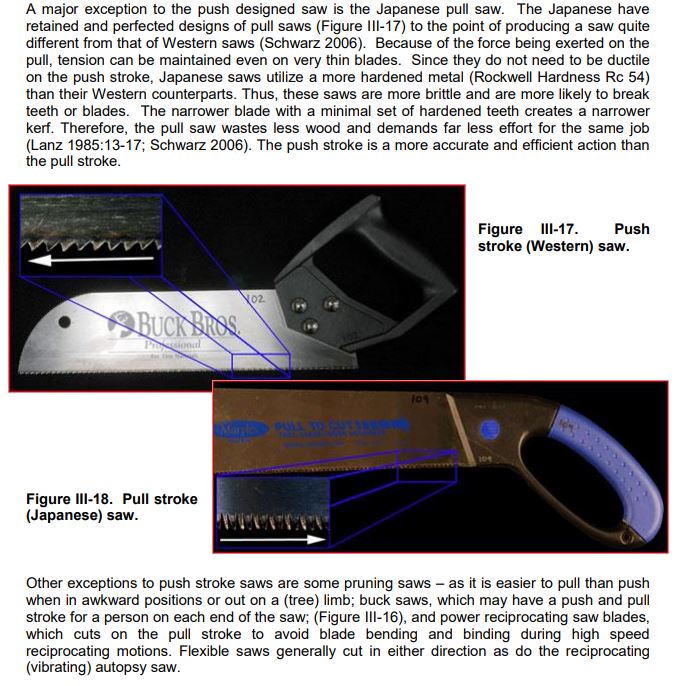

The act of sawing is essentially pushing, pulling or rotating the teeth of a saw blade in such a manner as to cut (needle point teeth designed like a knife) or chisel (teeth designed similar to a flat bottomed wedge) through material. To understand residual characteristics of saw cuts, it is necessary to examine the action of the saw blade. Saw action includes the slicing or shaving of a knife blade or chisel tooth through material, as well as the actions of the banks of teeth working in unison or opposition to the blade. Since the saw teeth perform the cutting, actions of each tooth and the combinations of these teeth on a blade must be examined. Saw actions need to be examined in terms of size, set, shape, power, and direction of cut as well as how

these various actions influence the cut material (Symes et al. 1998; Symes et al. 2002). ”

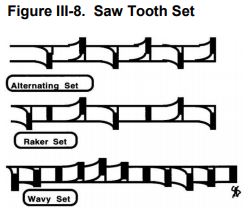

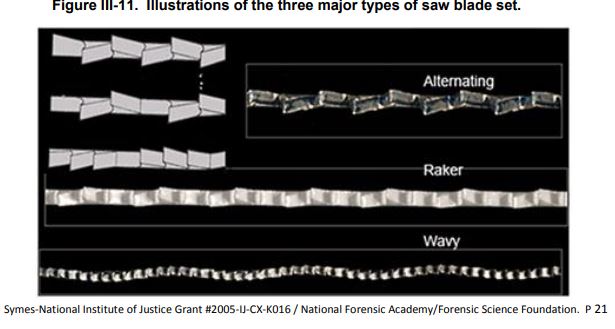

There are three types of sets used for spacing and arranging saw teeth: alternativing, raker, and wavy (Figure III-11).

Symes S.A., Chapman E.N., Rainwater C.W., Cabo L.L., Myster S.M.T. (2010). Knife and Saw Toolmark Analysis in Bone: A Manual Designed for the Examination of Criminal Mutilation and Dismemberment.

https://www.crime-scene-investigator.net/KnifeAndSawToolmarkAnalysisInBone.pdf

======

https://www.fix.com/blog/table-saw-joinery-techniques/

======

Common crosscut saw tooth patterns

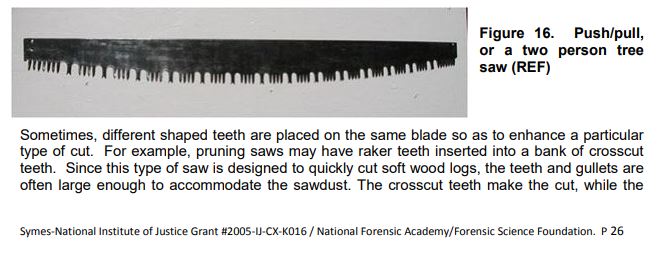

“Until the 15th century, the two-person crosscut saw used a plain tooth pattern. The M tooth pattern seems to have been developed and used in south Germany in the 1400s. Even as late as 1900 most of the European crosscuts still used the plain tooth pattern with a few exceptions of M tooth being used. Not until fairly recently was the saw with a raker or “drag” developed.

In the case of plain, M, and Great American tooth patterns, each tooth both cuts the wood and clears out the shavings. However, in the case of the champion, lance, and perforated-lance tooth, cutter teeth cut the wood fibers and the rakers remove the scored wood from the cut”

Miller, Warren (1977). Saw Manual, p. 2 The Crosscut Saw. The USDA Forest Service

https://www.fs.fed.us/t-d/pubs/htmlpubs/htm77712508/page02.htm

======

Figure 9—The configuration of the teeth of a

Figure 9—The configuration of the teeth of a

crosscut saw. This is the perforated lance tooth pattern

“Tooth Spacing

The teeth of most crosscut saws lie on an arc of a circle (figure 3). This is sometimes called the circle of the saw, or the arc of the saw. This arc makes cutting faster, easier, and smoother. Especially on larger trees, when more teeth are being used, the arc causes the teeth to share the workload progressively instead of all at once. The circle of the saw works in conjunction with the arc of the sawyer’s arm to effectively deliver power to the saw teeth as the saw feeds itself into the log.

The spacing of the saw’s teeth ranks in importance with tooth pattern. Saw designers had to consider questions such as:

- Is the tooth strong enough for the intended work?

-

Are the gullets far enough apart to effectively pick up all the fibers severed by the cutters?

- Is there enough room for the teeth and rakers to be sharpened and maintained?

- What’s the best way to reduce vibration and chatter so the saw cuts smoothly

The answer to these questions centers on tooth spacing. Generally, the longer the saw, the larger the teeth and the wider the space between teeth. Knowing tooth spacing helps the sawyer select the proper length of saw. Larger crosscut saws, with more space between the teeth, work poorly on small branches. Likewise, a small saw with small, closely spaced teeth doesn’t work well on large trees or logs.

Tooth Patterns

For centuries, only the plain tooth (or peg tooth) pattern was used. Modifications to the plain tooth pattern were developed to make the saw easier to use. We will discuss six patterns: the plain tooth, the M tooth, the Great American tooth, the champion tooth, the perforated lance tooth, and the lance tooth.

Plain Tooth (Peg Tooth) Pattern

This pattern just includes cutter teeth. It is best used for cutting dry, very hard, or brittle small–diameter wood. Examples include many bow saws and pruning saws. These saws do not have special large gullets for sawdust. The sawdust is carried out in the small spaces between the teeth. Wet or resinous sawdust can bind up this tooth pattern.

The M tooth, still manufactured today in a modified form for competition saws, dates back to the 1400s in southern Germany. This tooth is designed to cut the fiber, break the severed fiber, and clean out the shavings. The tooth pattern consists of pairs of teeth set alternately and separated by a gullet. The outer edges of the teeth (the legs of the M) are vertical and act like rakers. The inside edges of the M are filed to a bevel, making a point. This tooth pattern is best suited for cutting dry, medium–to–hard woods.

This pattern consists of a group of three teeth, each set alternately, separated by a gullet. It is sometimes called a crown tooth because of its shape. The Great American tooth pattern is designed to cut dry, medium–to–hard woods. A special file is used for these saws. The file can be purchased today and is called a crosscut file or a Great American file. The file is shaped somewhat like a teardrop. The thicker rounded edge is for filing out the gullets. The sides of the file are used to file the rakers and cutters. This file also can be used to sharpen other tooth patterns.

This pattern is especially popular in the hardwood regions of North America. It consists of two cutter teeth set alternately and an unset raker with a gullet between them. The cutters are wider and more massive than the lance tooth pattern, allowing heavy sawing in extra hard, dry, or frozen wood. The larger teeth are sharpened in more of an almond shape rather than in the pointed shape of a lance tooth.

The lance tooth pattern also may be called the racer or four–tooth pattern. For many years the lance tooth pattern was the standard for felling and bucking timber in the American West. It consists of groups of four cutters set alternately, separated by an unset raker with gullets on each side. The lance tooth pattern is best suited for cutting soft green timber, especially fir, spruce, and redwood.

Perforated–Lance Tooth Pattern

This tooth pattern is considered a general utility pattern that can cut all but hard and frozen wood. It consists of groups of four cutters set alternately separated by an unset raker with gullets on each side. The “bridges” between the teeth form the perforations that give the pattern its name. These bridges strengthen the teeth and reduce chatter when the saw is used to cut harder wood. The perforated lance tooth pattern is sometimes called the racer pattern and old–timers called it the four–tooth pattern. It was popular historically in the pine country of the American West, and is still popular there.”

https://www.fs.fed.us/t-d/pubs/htmlpubs/htm04232822/page04.htm

======

Thompson T.J.U., Inglis J., (2008). Differentiation of serrated and non-serrated blades from stab marks in bone. International Journal of Legal Medicine. 123(2):129-35.

======

| WEAPON | ||

|---|---|---|

| CHARACTERISTIC | SERRATED | SCALLOPED |

| Weight (g) | 860 | 820 |

| Length (cm) | 30.4 | 30.5 |

| Width (cm) | 2.54 | 2.54 |

| Blade Length (cm) | 4.825 | 5.014 |

| Blade Width (cm) | 1.527 | 1.751 |

| Number of Teeth | 40 | 8 |

| Teeth Per Inch (TPI) | 29 | 6 |

| Beveling | Yes | No |

| Number of Sharp Edges | 1 | 1 |

Table 1: Summary of weapon characteristics.

=======

https://ecommons.txstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10877/4186/TEGTMEYER-THESIS.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

http://everydaycarry.com/posts/17367/whats-better-for-edc-plain-vs-serrated-vs-combo-knives