Art and Architecture;

National Museum of Phnom Penh

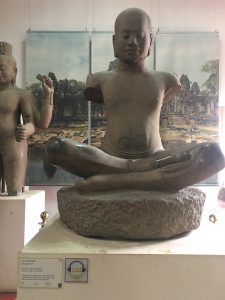

The streets of Phnom Penh are fast passed cacophony, of colors from the street side vendors, to blaring horns from the whizzing motos, with shouts of “Tuk Tuk!” by their eager drivers sitting idle… to the untrained eye it’s uninhibited chaos. Subtly it’s a neatly choreographed flow, like rapids in a river. The shimmering Tuk Tuk’s gleam like fish, as the motos swim in and out of traffic, stopping briefly to buy the neatly bagged drinks to go or sliced mango and sticky rice. One can find serenity amongst it all, like a the rushing water of the rapids or be crushed by the force against jagged rocks in its river. It is with such a great force as this the subtle Khmer form was presented in their stone figures the At the height of their creative arch. The slight give of the hip, the ancient metaphor in the placement of a finger, the sand stone texture, smoothed, reflects the tone of the makers skin as of each granule is a hair follicle of its own.

The height of the Khmer dynasty and subsequently their art came with Jayavarman VII with his fulfilling of royal obligations to build ancestral temples in the traditional fashion, at what is now seen as the twilight of the age on Angkor at Bayon period of the late 12th century. For four centuries the Khmer held a royal lineage of power at Angkor, but but their history reaches as far back to artifacts found in Bronze Age of around 300 BCE. However from the middle of the second century to the end of the 8th the Khmer people fought and struggled to hold a seat of power. It is by the Sdok Kak Thom a stele of sand stone written in all four sides in Sanskrit and Ancient Khmer. It’s dated 1052 but depicts a time at least 250 years earlier and denotes the rightful power and ritual used to inaugurate family Shivakaivalya by the Brahman Hiranyadama, the consecration of the devaraja Jayavarman. The Brahman was a holy keeper of the cult of devaraja, and recited the holy text Vinashika and taught the rights Shivakaivalya. Who by some scholars say this was a right passed and recreated with each monarch after words, it is in this ceremony that is associates the monarch with power of the “linga” holy text and in its self Shiva, the king God of the Brahman. This in turn tied the king to Shiva making him in some translations a God King. “The ceremony defined the ruler by making him a portion of Shiva and forged a threefold relationship among the officiant Brahman, ruler and linga”1 later the Sanskrit translation is thought to be a translation of a Khmer word phrase for local deity, and older and indigenous symbols of power2. It is here at the earliest history of Cambodia and the Khmer region we are shown how important state power through right and ritual was tide to religious practice, not only that but the also the influence through the outside world by trade, and later missionaries not only formed but combined with local traditions. This is a subtly complex arena that unfolds until present day, but now we choose instead not to look at the politics but instead to focus on the evolution of Khmer design and the refinement of expression of gesture. It is now how ever important to note that this early ceremony took place in what is believed to be an early ninety century temple called Krus Preah Aram Rong Chen. Now mostly ruins it is concluded to have been a three tiered pyramid, it was from this archetype that the dramatic structure that come to represent Khmer civilization would evolve. From these meager ruins, to the ceremony preformed for Jayavarman VII at Angkor what that stand today. The nearly ten centuries of refinement also hold a complex form of syncreticism which shaped Khmer belief and culture. The most distinct characteristic of their artistic achievement is found in the subtle form of naturalism. In such early masterpieces of Harihara with a gentle hip-swayed stance of holds a graceful form as if to walk causally over to the viewer. As with the pyramids that were built to honor a family obligation as well attach the monarch to a holly position, so to the naturalism’s casual gesture continued, as seen with the slight smirk in the serene head of Jayavarman VII. This sandstone bust “epitomizes the spirituality and humanity…showing a state of emptiness and peace of the Buddhist monarch. Deliberately reference to the Buddha intended to suggest the kings embodied the wisdom and compassion of the Great Saga”3. When seeing these works among many others and understanding the centuries carried between them, the melding of cultures and practices, one can truly enjoy the slower pace of life amongst the rapid chaos of the streets.

1Helen Ibbitson Jessup “Art & Architecture of Cambodia” Thames & Hudson world of art. p.62-63

Be First to Comment