Revised Program Description:

“Local and Global Reform in The American Food System” is an SOS designed to explore local and global food systems and the inequities that exist inherently within them. For this contract, the student will work with Seattle based non for profit Community Alliance For Global Justice to explore questions of commodification and the impacts of corporate involvement in a capitalist food system.

By assisting in research work, event planning, community involvement and using Kyla Wazana tompkins’ Racial Indigestion as a primary text, the student will come to an informed stance on the subject, participate in weekly seminars and create bi-weekly writing pieces as evidence of her learning.

Self Evaluation:

Though this quarter was not my first experience working independently at Evergreen, it was my first time in an SOS. After spending the second half of spring quarter and the entirety of fall quarter working away from the Evergreen campus I was excited to spend my Tuesdays in Olympia and rekindle my connection with the Evergreen community while maintaining a sense of independence in my studies. What was explored in this class is summed up succinctly in Kyla Wazana Tompkins’ conclusion from Racial Indigestion where she asks “When and why did eating become a way of asserting racial, not to mention class, identity? How does an act which is so policed and so overdetermined- eating- also come to be affiliated with transgressive pleasure, with sex, sexuality, and an eroticism that is all its own?” (p.184). This quarter, class discussions and reading texts like Tompkins’ have reinforced my obsession with food and inspired me to continue to pursue what I am passionate about.

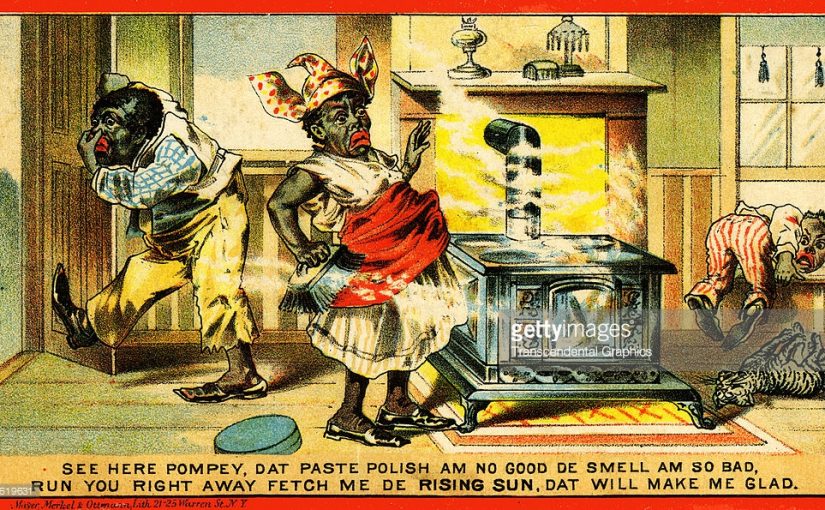

Seminar has always been one of my favorite aspects of the Evergreen learning community. This quarter reading Kyla Wazana Tompkins’ words on white supremacy, sexual desire, and oppressive food practices through the lens of “critical eating studies” in Racial Indigestion has been my most inspiring and interesting seminar text to date. Despite her dense passages and difficult concepts, I was never tempted to rush through chapters and found myself able to fully digest her text (often after several readings). Her ability to articulate concepts I am deeply interested is motivating and inspiring. I hope one day to be able to explore food, culture, and politics as deeply as she has. I felt invested in all seminar conversations this quarter and walked away each Tuesday feeling inspired by the insights my classmates and faculty so often provided. Reflecting upon my seminar writings this quarter I feel most proud of my week 6 essay “Wholesome Girls and Orientalism” in which I explored Tompkins’ text in relation to an article entitled High/Low Cuisine and Orientalism and came to the conclusion that “In Antebellum (and many current day American racial discourses) orientalist discourses, the western observer/ traveler/ historian maintains their place of superiority by continuing to confine the non-westerner as an observable anomaly, while failing to acknowledge their whole personhood. The constant consumption and colonization of the “other” ensure the subordination necessary to rationalize exploitation and lack of humanity, it is in this mindset that black and brown bodies turn less into people and more into “things”.” I enjoyed the assignment format and its interdisciplinary nature and the synthesis it prompted.

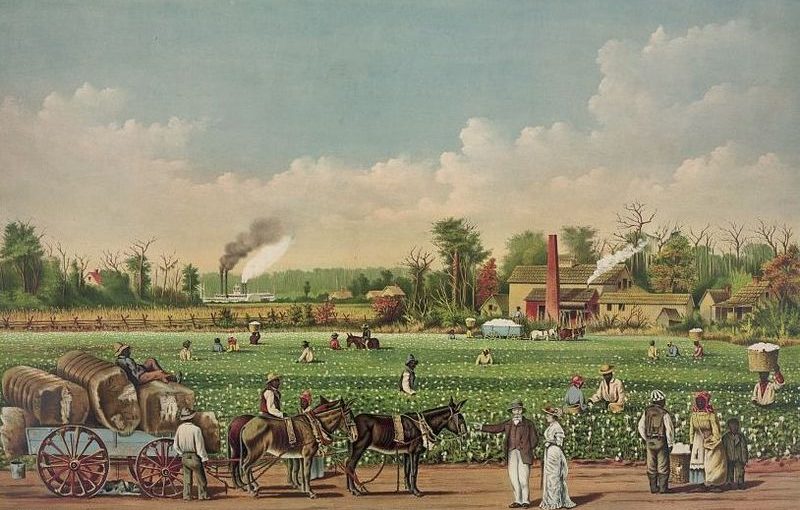

Bringing the body into academia this quarter through our tasting labs felt appropriate and necessary while reading Tompkins and Newman. Through Annie’s labs which related mostly to Racial Indigestion and Kotomi’s educational tea tasting labs we were forced to think of ourselves and our eating as more than just consuming, an act that in itself challenges the nature of current capitalist commodity culture. During Annie’s corn tasting lab we sat eating various preparations of corn (corn flakes, polenta, corn bread, bourbon, and high fructose corn syrup) while watching Michael Twitty’s “Black Corn” in which he explores corn’s designation as slave food during Antebellum America and the importance and varieties of corn that have been so essential to indigenous peoples across the Americas for millennia. In the past hundred years corn has been turned into a staple commodity in the agricultural industry, but in turn varieties so essential to native diets and culture have dwindled.

My in-program internship with Seattle-based organization Community Alliance For Global Justice has given me an inside look at the world of anti-oppressive grassroots organizing and what goes into event planning and community collaboration. Through outreach, social media, e-mailing and research, I was able to educate myself on ways to approach these subjects in a professional context. Most of the quarter was spent preparing for our March 11th Wild Salmon Cookout in collaboration with the Muckleshoot Food Sovereignty Alliance and in solidarity with northwest tribes. In preparation for the event and solidarity campaign, I conducted extensive research on the issue of Genetically Engineered salmon and the threat corporate ownership of an animal that coast Salish people have organized their lives around for millennia holds. I walk away from this quarter with a sense of pride in the work I have participated in and was delighted to see the impact our event had on people that attended. I am also honored to say that my article “Genetically Engineered Salmon Cause Threat to Wild Salmon Populations and Local Tribes” was published on the Community Alliance For Global Justice website.

Though at first, I felt a sense of frustration in the fact that so much of my internship work was not suitable to share on my website, I found ways around it and was able to turn my research on genetically engineered salmon and food sovereignty into informative posts. Despite initial confusion in regards to what was expected on the website for tasting labs, I was able to share my learning through brief yet thoughtful post tasting lab reflections. Seminar papers were the easiest to incorporate into my website and I enjoyed coming up with creative titles and eye catching images to share. At this point, I feel as though I have mastered wordpress and feel comfortable creating simple but visually appealing websites.

This quarter has by no means been an easy one, between balancing schoolwork, an internship, a new job, and chronic illness I spent many moments feeling as though I didn’t have time to gather myself enough to comprehend what my body and mind were telling me. Regardless, I walk away from this quarter with a sense of pride. Looking back on the quarter, I am finally able to breathe and acknowledge the hard work I have completed over the past 10 weeks. Spring quarter I will be taking a leave of absence in order to prepare myself for a thesis I plan to write Fall 2017. Though I won’t be on the Evergreen campus next quarter, I plan on continuing in my work with CAGJ indefinitely and look forward to Summer quarter when I will participate in Sarah Williams and Martha Rosemeyer’s Farm-to-Table: Slow Food in Denver and on Campus. I am glad to have had the opportunity to participate in this SOS and have no doubt that many of the connections and insights I have gained in the classroom will last long beyond the quarter and my time at Evergreen.

Final Presentation Slideshow:

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/19SfQo8TceodBM6PUvJjFCPyyZsfdYOFbwOEyzzSlTJU/edit#slide=id.p