SOS_Presentation_wk10

Author: stecol11

Salish Agriculture

Komo Kulshan, or Mount Baker, is an active volcano in the northern Cascade Range of Washington state. Fertilized by Komo Kulshan’s volcanic events and millennia of salmon spawning, the Skagit River Valley, just southwest of Komo Kulshan, hosts some of the most fertile soils in the world.

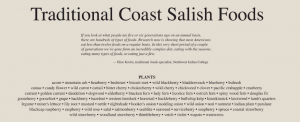

Inhabited for at least ten thousand years by Coast Salish First Nations, the Skagit Valley’s ecosystem has changed greatly and rapidly since settlement by Europeans in the late 19th century – as seen in the figure below, the Skagit Valley grows over 90 commercial crops – of these crops, four are native to Northern America: pumpkins, corn, raspberries, and blueberries.

It is interesting to contrast these crops with the 70-odd crops eaten by Coast Salish Nations prior to European arrival. Some of these crops have horticultural value in the current marketplace such as: blueberries, salal, spruce, raspberry, oaks, strawberries, and vetch.

And below, a chart showing what the Skagit River Estuary area would have looked 10,000 years ago.

The Skagit River is in close proximity to the San Juan Islands – which were named after San Francisco De Elize in 1792. Settlement by Europeans was not made until 1845 when the Hudson’s Bay Company claimed San Juan Island. Prior to this settlement, Coast Salish groups inhabited the islands for at least 8000 years.[1]

When they were gathering food the Indian people never stopped in one place. Didn’t have no reservation then. They went from place to place… They had seasons for these moves. Like right now there’s the herring season… Steelhead run in December… They know when the clams are good. They know all these seasons. — James Joseph[2]

This food management strategy sounds like what agriculture should be attempting to achieve – natural regeneration of resources powered by the changes of season. European settlers have been actively farming the Skagit River for about 170 years – that’s about two percent of the total time that Coast Salish peoples have inhabited the area.

The San Juan Islands Agricultural Guild perennially hosts an Agricultural Summit for the San Juan Islands agricultural community. Farming on the San Juan presents an interesting challenge – the soils are relatively poor in the area, deer populations are rampant and unbalanced, and the islands experience high-population fluctuations in the summer seasons. Furthermore, each island has distinctive topography.

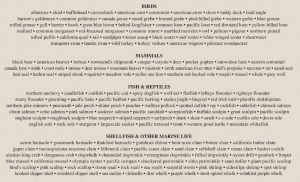

Below is a photo of birds, mammals, and sea-based proteins that were eaten by First Nations of the Pacific Northwest.

Is cormorant the next trendy protein on restaurants’ menu?

[1] https://www.nps.gov/sajh/learn/historyculture/the-pig-war.htm

[2] edited by Ann Nugent, with special assistance from Eva Kinley ; drawings by Adrienne Hunter. (1982). Lummi elders speak. Lynden, Wash. :Lynden Tribune,

Organic Demand, Conventional Supply

If you have eaten an organic egg in the United States, there’s a good chance you’ve indirectly eaten grains that were shipped across the Pacific Ocean.

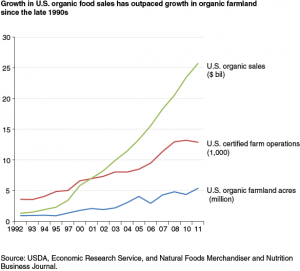

Consumer demand for organic products in the United States has grown by double-digits nearly every year since the 1990s,[1] yet only 0.8 percent of U.S. farmland is certified organic.[2]

This has led to imports of organic corn into the United States more than tripling from 2015 to 2016.[3]

To help aid farmers who are transitioning to organic production (and to increase supply of domestic organic products), the Organic Trade Association and the USDA recently (January 11, 2017) developed a national program to develop a federal Certified Transitional label for crops and farmland in transition to USDA Certified Organic production.[4] Kashi (now owned by Kellogg’s) and the organic certifier Quality Assurance International (QAI) have created their own Certified Transitional label to help sell their emerging product lines that use “Transitional Organic” crops.[5]

QAI’s Certified Transitional Label on store shelves.

QAI’s Certified Transitional Label on store shelves.

For farmland to produce USDA Certified Organic crops, it must have had no synthetic fertilizers or pesticides applied to it for at least 3 years before harvest of the marketable product. For agricultural producers with cropland in non-organic production who are seeking to transition to USDA Organic production, this regulation forces agricultural producers to produce crops using USDA Organic practices that cannot be marketed as USDA Organic.

The new federal Transitional Organic label should help producers financially bear the period of time in-between conventional and organic production.

A recent event at the biennial Organicology conference convened a meeting of industry stakeholders to discuss the changing organic market. I have distilled key points below.

- agricultural producers do not know what to plant for the following seasons

- some organic famers need contracts to plant anything in the ground

- according to the Organic Trade Association, millennials account for 52 percent of organic purchases in the United States of America

- it’s imperative that buyers know how much the farmers need to make to make food production long-term profitable

- on the same token, transparency on the buying side is imperative as well

- a representative for Kashi said they have five products on the market and people “love” hearing about the story of moving towards Organic production. Kroger was highly interested. Kashi now has 3500 acres in transition this year, up from 848 in 2015.

- a study conducted by Edward C. Jaenicke of Penn State University showed that counties with high level of organic agricultural activity had lower poverty rates and higher median household incomes.

[1] http://ota.com/sites/default/files/indexed_files/OTA_StateofIndustry_2016.pdf

[2] https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/organic-production/documentation/

[3] http://www.seattletimes.com/business/as-demand-for-organic-feed-surges-us-cows-feast-on-romanian-corn/

[4] http://ota.com/news/press-releases/19470

[5] https://transitional.kashi.com/en_US/home.html

People, Planet, and Profit for Good

The word corporation, from the mid 15th century, means “persons united in a body for some purpose” and stems from the past participle corporare of Latin, which means “to embody”.

Ideally, a business is a group of ideas and people work together to present or “embody” solutions or innovations. The largest corporations, such as Walmart, Samsung, Exxon-Mobil, Apple, British Petroleum, all represent the solutions their respective companies pioneered.

The Triple Bottom Line is a common accounting framework for corporations that use three metrics to judge overall success and value as a business: social, ecological, and financial sustainability.

Triple-Bottom-Line. Wikimedia Commons. Author triplebotline.

Walmart might be revenue positive at ~450 billion USD a year, but does it supply chain contribute to the long-term production of its goods? Does the working climate at Walmart contribute to human happiness? Walmart might provide millions of jobs, but if its employees are not empowered, which potential positives is the company losing?

Identity-Preserved Malt

Fermented alcoholic drinks have long been a component of human societies – Ninkasi – the Sumerian goddess of beer, now serves as a namesake for a popular brewery in Eugene, Oregon. Beer is typically composed of four base ingredients: grains (typically barley), hops, water, and yeasts. From 2008 to 2015, the amount of breweries in the United States more than doubled from 1500 to 3500,[1] due to the proliferation of independently-owned microbreweries. Often these breweries tout their products as “local beers” – but is it possible to tell where ingredients used in American breweries actually originate?

Purple Egyptian Barley from Palouse Heritage

Purple Egyptian Barley from Palouse Heritage

www.palouseheritage.com

Barley is the fourth-most cultivated crop in the world[2] – it’s an adaptive grass that has long been used as a staple-food, for livestock feed, and as a material for distilled beverages. Grains used in beer are often “malted” – to make malt, a grain like barley must be germinated and then heated to terminate further germination – this process converts starches in the grain to sugars. In 2009, the state of Idaho produced a staggering 2.6 billion pounds of barley, or 28 percent of the total barley produced in the United States.[3] There are a primarily two companies who malt grain in bulk on the west coast – Anheuser-Busch and Great Western Brewing Company. These companies will facilitate crop contracts with local barley producers to secure supply for their malting floors. After the barley is acquired after harvest, it gets aggregated in these companies’ malting floors and produced into bagged malt which is then distributed to local breweries. After the barley is aggregated it becomes impossible to tell from where the barley originated.

Two smaller malt companies have recently started in the Pacific Northwest – one being Skagit Valley Malting, in Burlington, Washington State, and another being the Local Inland Northwest Cooperative in Spokane, Washington State. These two companies have started producing identity-preserved malts – or malts that can be tracked to the field in which they were grown. As consumer demand grows for transparency in the agricultural supply chain, identity-preserved malts offer a way for people to truly know origin of the product they are consuming. As the craft-brewery scene becomes saturated, will identity-preserved malt provide a way for breweries to distinguish themselves and provide a better product?

[1] http://time.com/money/4596638/america-record-high-craft-breweries/

[2] http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC

[3] https://barley.idaho.gov/pdf/quality_reports/2009.pdf

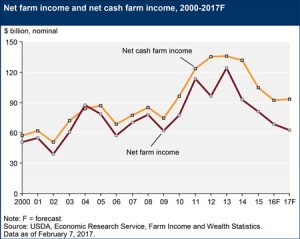

Dwindling American Net Farm Incomes

Net farm income refers to the monetary return to farm businesses for their labor, management, and capital after all expenses have been paid – in 2017, the net farm income is forecast to decline by 8.7 percent to $62.3 billion, the fourth consecutive year of declines after reaching a record high in 2013.[1]

If realized, net farm income in 2017 will be the lowest since 2002, in inflation-adjusted terms. [1]

An analysis by the Federation of American Scientists on the current status of the United States’ agricultural economics reads –

The outlook for a fourth year of lower net farm income, coupled with a third year of lower farm wealth, suggests a weakening financial picture for the agricultural sector as a whole heading into 2017, with substantial regional variation. Relatively weak prices for most major program crops signal tougher times ahead. Low prices are expected to trigger substantial payments under the new safety net programs of the 2014 farm bill; however, eventual 2017 agricultural economic well-being will hinge on crop prospects and prices, as well as both domestic and international macroeconomic factors, including economic growth and consumer demand.[2]

Agriculture is an inherently volatile industry – through which means can we increase the profits of farmers whilst keeping food costs low? How can we invest in rural infrastructure that supports livelihoods and happiness?

[1] https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-sector-income-finances/highlights-from-the-farm-income-forecast/

[2] https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40152.pdf