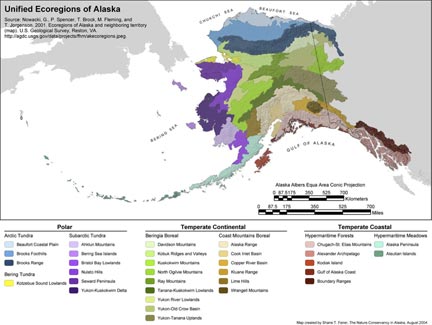

Alaska is a state with vast lands totally over 663,300 mi², it contains 32 various ecosystems ranging from the southern temperate rain forest to the northern tundra. Alaska is an area where extraction industries drive the politics and economy. It is only natural to want to protect those lands from that industry; one that thrives on the exploitation of the land in the most extreme sense. The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 sought to protect some of Alaska’s acreage from that destructive force.

The ANILC designated 157,000,000 acres of land for conservation, this includes National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, Wild and Scenic Rivers, National Monuments, recreational areas, National Forest, and general conservation areas. Glacier Bay National Park was one of many lands set aside in this act. The ANILC came about after the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, this act gave Native peoples rights to 44 million acres, and approximately 962.5 million dollars for its future claims on other land. Within the ANCSA, the Secretary of the Interior was to set aside 80 million acres of land for the future potential to become National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, Wild and Scenic rivers, or National Forest. The ANCSA also set specific time frames for the designation of the land, Congress had 5 years to pass legislation or the land would be up for re-development.

This provision in the ANCSA would set the stage for the ANILC to be passed in 1980. As per usual in the struggle for land and land conservation, Native peoples led the way and made it possible for all of us to enjoy Alaska’s unique ecosystems.

In the years following the ANCSA there were many attempts to pass a bill in Congress for use of the set aside land. As you can imagine oil, timber, mining, and gas corporations fought tooth and nail not to see any of them passed. It became so strained that nearing the end of the 5-year period in which Congress had to designate the land, President Carter was forced to use the Antiquities Act to designate 56 million acres for National Monuments. The move was not a very popular one especially for those living in Alaska, many of them participated in civil disobedience against the Presidential Order.

In superb capitalist fashion, the ANILC gained significant support though out the years, even by those in opposition, because Alaska experienced a boom in its tourism market after these lands opened for public use. That would mark the beginning of the commodification of land use and natural spaces in Alaska. The argument is not against the ANILC, a wonderful act to keep lands out of the hands of extraction corporations, rather that the management of the lands exist in a system that needs to show profit margins. This creates a very human centric model that forces the land (and its inhabitant) to be crafted as finely as any clay pottery. I will be discussing different management plans in place that coordinate human/other species interactions; and in fact, put the concerns of visitors above lifelong residents. This is a day where we seek experiences not objects, and the Outdoor industry wants to cash in on that very need.

Leave a Reply