This week, I found myself in the midst of a nasty cold, which definitely curtailed my productivity. However, towards the end of the week, I was feeling better, and had the opportunity to cook a meal for my friends to celebrate my birthday.

I always feel strange celebrating my own birthday as the center of attention. Really, my birthday has nothing to do with me; if not for my parents, I wouldn’t be here. If not for my friends, I would have nothing to celebrate. It was important to me to do something to celebrate them and in that, celebrate my own birth and life. So I decided to cook a big meal for them. As a person who often has trouble expressing love and appreciation effusively, food has become an important means of communication. And in my study of food and its interaction with people, this practice has only become more significant. This meal was an opportunity to combine my love of cooking and food with my studies and my desire to do something nice for the people I care about.

Luckily, I have some pretty spectacular friends who wanted to help me cook the meal, for which I cannot thank them enough, as it was quite a lot of work. My best friend Grace drove up from Portland to celebrate with me, and we hosted the dinner in my dear friend Roquin’s campus apartment. He was kind enough to clean and decorate the space with beautiful fresh flowers and balloons, and then helped us make the meal. Also, Natasha arrived a few hours early to help cook, and brought beautiful orange flowers.

Together, we made (vibrationally) an Italian dish, some variations of which my Italian grandmother and (less Italian) parents have cooked for me dozens if not hundreds of times. We worked without a recipe, simply combining ingredients until the pan sizzled right and the smells became dangerously enticing. It was pasta with an olive oil sauce, including asparagus, tomatoes, garlic (of course), shrimp, and other ingredients. We also made a fennel & grapefruit salad and Roquin steamed some veggies for the side. For dessert, Grace baked an unparalleled Pavlova that had us all heading for seconds.

The research and planning that went into this meal was significant. Firstly, I had never cooked a meal for so many people. Figuring out the logistics and budget was a challenge, and one that involved comparison shopping at Grocery Outlet, Safeway, and Bayview to try to find where I could source the most organic ingredients for the lowest price.

Second, I wanted to cook a meal that reflected my research into food and connected my heritage to the celebration. In Italian families, food is often the gathering point of community, whether for conflict or celebration. According to Simone Cinotto, author of The Italian American Table,

“Not only has food been the most eloquent symbol of collective identity for Italian Americans throughout memoirs, literature, poetry, and the visual arts, but generations of social workers, sociologists, anthropologists, and other observers have also described the way eating becomes an act of self-identification and pride for Italians and an occasion for asserting cultural and political claims.”

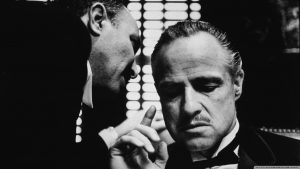

A screengrab from one of my favorite films about Italians (and the food we eat – don’t forget, Don Corleone used to run a grocery store!)

When I share Italian food with my friends, I am not just cooking them a meal, I am offering them a taste of my heritage. A part of that heritage is what Smart-Grosvenor would describe as “vibrational cooking.” When I turned 18, I asked my Italian grandmother to make a book of her recipes to share with me. After watching (and helping) her cook various dishes for years, I was hopeful to try my hand at it. She made me an incredible book of recipes, but one that was incomplete – so much of the knowledge of how to make good food is shared verbally and in the moment.

Each time I cook from her recipes, I spend less time thinking about what is on the page and more time thinking about the principles of flavor she has taught me: you have to brown the onions in the bottom of the pan, then add the garlic, but don’t let it go too long, or you won’t be able to taste it. You have to buy the canned tomatoes imported from Italy – the other ones just don’t taste as good. You use fresh basil and dried oregano. To keep the meatballs solid, mix crushed unsweetened cornflakes into the meat. To cook this meal, I decided to rely on my intuition rather than any specific recipe, and shopped by what was in season. For example, I learned from Kat that asparagus is sprouting right now, and included that in my dish.

Another aspect of Italian cooking is gender. Something I have struggled with as a feminist but also a person attracted to many traditionally feminine roles, such as “caregiver,” “mother,” “cook,” or just “caregiver,” I find difficulty in cooking food, especially for men, if I feel that them seeing me in that role will lessen their respect for me. It is an unfortunate lesson that I have had to learn: all too often, one offer of labor begets the demand of another. On one occasion, I cooked a meal for my friends, and then they watched as I did every single dish afterwards. I reprimanded them for not offering to help clean, but apparently the message didn’t go through. The next day, one of the boys I had shared the meal with asked me to do his laundry for him. Each time I cook, I fear that it will teach people to feel entitled to that labor from me again. I am unlikely to cook for someone who I do not care about and respect. That imbalance of gender also has roots in Italian-American culture.

“In her early classic study of the Italians of Buffalo in the peak years of immigration between 1890 and 1930, Virginia Yans-McLaughlin set the tone for discussion to follow: ‘All provide evidence for the cohesion of both nuclear and extended [Italian immigrant] families. . . . On the whole, they maintained strict sex role definitions and an adult-centered family structure.'”

This inflexibility of roles, though not supported by actual oppression that I can perceive within my own family, is clear. My grandmother is a second-generation Italian immigrant. Her mother, born in the US cooked meals every night from the fruits and vegetables grown in my great-grandfather’s garden, with fish and seafood he, an Italian immigrant, had caught in the ocean that day. The roles were clear – her father brought the food, and her mother prepared it. But even that definition was shaky and individualized within their experience – my great-grandfather loved to bake bread.

In fact, in his retirement, he cooked meals for a local elementary school each day. The more time they spent in America, the less those clear roles of gender acted in their lives. My grandmother proudly carries that tradition – she loves to feed her family. My grandfather rarely cooks, and most often when he does it’s his world-famous tomato sandwiches. But I don’t honestly believe that they fell into those roles because of oppression or even really because of their genders. There is something fundamental in certain human beings that demands they express love through food. I don’t know what it is or why it exists, but I certainly have it.

There is nothing so intensely entrenched in my family history in the other dishes we prepared, though there is a historical significance to the dessert. The Pavlova is a perfect dish for spring, made with a light meringue, whipped cream, and fresh fruit. The dish actually originated in the United States, despite being named after a Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, who repatriated to England later in her life. There is even some believe that Anna Pavlova licensed her name, as it appears in so many dishes; 1,024 in fact. She was a businesswoman as well as a ballerina.

The Pavlova as it is now prepared became a common dish in the 1920s, based on a German torte, evolving into a gelatin-based dish, and eventually to the fluffy meringue we know today. It was a shift originally credited to, of all groups, New Zealanders, with the incorporation of cornstarch into the recipe. Now we know that the dish first took on this form in the US with the introduction of maizena to the dish. However, it remains an extremely popular dessert in Australia and New Zealand. According to Dr Andrew Paul Wood Annabelle Utrecht in this article, “The pavlova has meaning for people, our national identity as New Zealanders and Australians, we have latched onto it and it is now part of our mythology.”

In the history and preparation alike, it was an incredible meal, thanks entirely to the lovely humans I made and ate it with. Though food studies can sometimes feel less food-based and more scholarly, for my birthday, I had the opportunity to combine my scholarship with the work that I most enjoy, and make with some of my favorite people, a meal that felt more like love than labor. If the rest of my 19th year even halfway matches the joy and fulfillment of its first day, I will have an incredible year.

May 2, 2017 at 5:53 pm

We missed you but were so happy to know you were celebrating in the spirit of love by nourishing your body and soul with dear friends. 🙂

May 2, 2017 at 6:13 pm

<3