“If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.” -Bishop Desmond Tutu

There were moments this past week in which for the first time, I was forced to considered how far I would go for my beliefs. Would I leave my bed at midnight (voluntarily) to stand with and support black students who were taken from theirs? Would I stand between them and police? Would I risk physical harm or losing credit to dedicate my time to the cause? These are questions I answered for myself, but couldn’t for anyone else. There are different forms of activism, different ways to help. In this case, I wasn’t sure how to be most effective. In fact, I’m still not sure. But I decided I would be there either way.

There has been a lot of coverage of events at Evergreen, none of which tells even remotely the same story I have experienced here. I don’t know how to reconcile the two, and I’m not here to tell “my” side – I want to protect the privacy of protestors and the movement. But I am confident saying that media has misreported moments for which I was present. The overwhelming narrative that these protests are centered around one racist faculty member, and not the systemic oppression of black folks (and other POC) at this school and everywhere, is false and not just a misrepresentation of, but a reductive insult to the protestors who have been working tirelessly to work towards creating a campus that feels safer and more supportive to students of color.

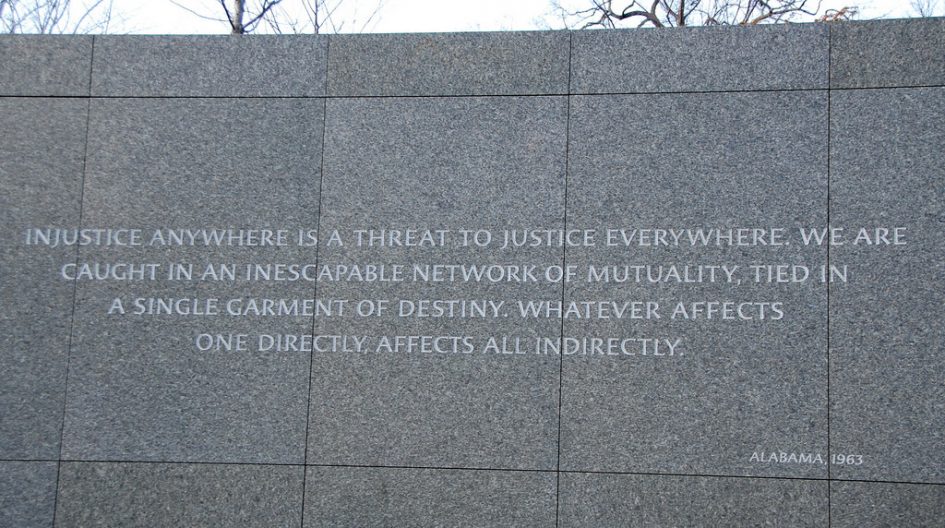

With that made clear, I would like to discuss how food and justice are connected and integral to protest movements, including the one on this campus. During the Civil Rights Movement, food was a central unifier around which people gathered, fought, and built community. Of course, the lunch counter is famous – in fact, it sits in the Smithsonian Museum today, and I have a photo next to it. But the lunch counter was just one of many places where food intersected with the larger movement. As we read in our Food First articles, SNCC relied on black agrarianism for food at different points.

According to this article from National Geographic, Georgia Gilmore, a Civil Rights activist who was fired from her job after supporting the bus boycott, was encouraged by Dr. King to open a restaurant, and “Gilmore’s home basically became an underground supper club. She ended up feeding hundreds, if not thousands, of organizers from her home kitchen, Carbone says.”

Paschal’s restaurant was also a common meeting (meat-ing) place for the Civil Rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia: “Owned by brothers Robert and James Paschal, the restaurant served free food and provided a safe haven for the leaders of the movement.”

In my experience with the protest movements on campus, food is a focus. For one, we often met during dinner hours on campus, so it was hard to access meals. On one occasion, the Flaming Eggplant provided free soup and bread for our meeting. On others, protesters flooded the Greenery, demanding food as their right in paying tuition to the school. Another focus of the movement has been divesting from Aramark, the supplier of food on campus, and a notorious corporation complicit in the prison-industrial complex which funnels black bodies into prisons to work for free or little pay in a form of modern-day slavery.

This week, I made brown bread, a typical peasant food during the French Revolution. The dish seemed á propos; brown bread’s virtues are extolled by French philosopher and early proponent of “communism” Jean-Jaques Rousseau as a component of his “ideal” meal, according to Thomas J. Craughwell. It is a simple dish, calling for only a few (readily available) ingredients, and is filling and long-lasting. It pairs well with stew, butter, jam, and whatever else is available. I used an Irish recipe, which had the fewest ingredients I could find, and was the most economical, in the spirit of the bread’s origins. The bread turned out well, and felt like a taste of revolution and self-sufficiency.

Leave a Reply