SOS: ComAlt, Seminar Pre-Writing Week 2

18 April 2017

Word Count: 310

Passages:

“We had a big house and a lot of land. That’s important! Some land! Black people got to have some land!” (Smart-Grosvenor 1970: 4)

“African Americans once owned 16 million acres of farmland… The rate of black land loss has been twice that of white land loss and today less than 1 million acres are farmed.” (Holt-Gimenez 2016: 3-4)

“Almost every other nonfieldworker I encountered in the tomato business was white, male, and sporting at the very least a few gray hairs… the type of guy you’d encounter on a Saturday on a golf course or in a bass boat.” (Estabrook 2012: 21-22)

News Media Context:

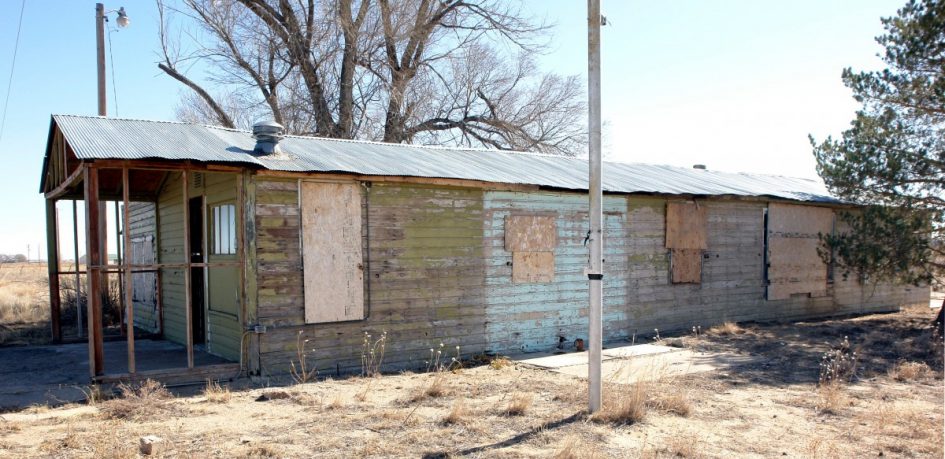

A Forgotten Piece of African-American History on The Great Plains

“Starting in 1910, Dearfield began attracting hundreds of black homesteaders from across the South, the Midwest and the eastern portion of the Plains. They came for opportunity. At its height in the early 1920s, 700 residents lived in town, with churches, a school, a blacksmith shop, a dance hall and a restaurant. And nearly all of the residents were black.”

Discussion:

A very clear common thread that I found throughout this week’s reading was the issue of a white-, male-dominated American agricultural system. With Shiva’s concept of a violent, masculine knowledge paradigm in mind, I found that I could very easily add the words “white colonialism” to that description. As Estabrook mentions, most of the people who control our modern agriculture are old white men who come from long lines of family money in agribusiness from farming to production.

As explained by Eric Holt-Gimenez and Breeze Harper, due to Jim Crow policy and other racialized government intervention, people of color are not only disproportionately laborers within the food system compared to their white, corporate counterparts, but their landownership had decreased throughout time despite the national visage of increasing racial equity. This disturbing fact adds to the paradigm of the broken food system, keeping people of color from achieving any sort of food sovereignty, and forcing many urbanized black people to rely on city permits and land trusts for community gardens.

Because of the current lack of black land ownership, I found myself feeling surprised during Smart-Grosvenor’s description of her father’s land. This sort of “huh, no kidding” reaction maintained as I read of black homesteaders inhabiting Dearfield, Colorado almost 100 years ago. As I reflect upon my own reaction to these facts, I attribute my shock to both my privilege of never having to truly consider the issue of black land ownership, but also to the regressive nature of this particular example of systemic racism that has increased in severity over time rather than improving.

I find myself asking questions such as, how, specifically, have we let this go relatively unnoticed? How would the food system change if we saw an increase in agricultural land owned by people of color, women, and first generation citizens? Would the knowledge paradigm inevitably shift?

Citations:

Estabrook, Barry. (2012). Tomatoland: How Modern Industrial Agriculture Destroyed Our Most Alluring Fruit. Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing.

Holt-Giménez, Eric & Harper, Breeze. (2016). “Food—Systems—Racism: From Mistreatment to Transformation.” Retrieved from https://foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/DR1Final.pdf

Runyon, Luke. (12 April 2017). “A Forgotten Piece of African-American History on The Great Plains” Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/04/12/521800847/a-forgotten-piece-of-african-american-history-on-the-great-plains

Smart-Grosvenor, Vertamae. (1970). Vibration Cooking: Or, the Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

Leave a Reply