I careened through the narrow streets; zipping between cars, pedestrians, and animals. We passed through clouds of diesel smoke streaming from truck engines like chimney stacks, billowing up all around us. I could smell the pungent scent of hot pavement and dust as it mixed with the auto emissions, a smell I had become all too familiar with. Taking public transportation in Ethiopia’s cities can be unnerving at first, especially while doing so in a contraption like the one I was currently riding in. I felt as exposed to the chaos of the streets as if I was an egg in a carriage. Such is the journey of the Bajaj, a type of motorcycle hybrid commonly used as a taxi substitute across the country. Bajaj is an Indian brand name, but they are usually homemade, put together haphazardly by whoever gets their hands on one.

Picture the front end of a motorcycle with the back wheel sawed off and replaced with a little two-wheeled wagon. The result is an awkward looking tricycle carriage. The taxi driver rides on the motorcycle in the front and directs the handlebars while the covered metal frame behind him can seat two or three passengers.

When I took my first ride I was a little worried, but I knew that this was the only way to get around. Instead of a door, I pulled back a multi-colored curtain and stepped inside. My heart racing, I looked around at the bizarre decorations. There were all kinds of symbols of the driver’s identity plastered along the walls. Posters and pictures of family and friends. Inspirational quotes. The faces of movie stars and local celebrities. It was like a whole college dorm room squeezed into a tiny space. For reasons I can’t understand there was shaggy carpeting dangling upside down from the metal roof, forming patterns of long strands that jiggled whimsically with each bump in the road.

No urban landscape in Ethiopia would be complete without the Bajaj. They were everywhere, and there was no getting around that fact. I would have to get used to it, like so many other changes, to make it through my trip. On any given day they can be observed weaving boldly through traffic like a network of fish navigating a coral reef. I took a deep breath and did my best to let go of the urge to control my own destiny, because at that moment it very clearly was out of my hands.

It was in this turbulent sea of traffic that I made the acquaintance of Daniel. I caught a ride with him at the end of an exhausting day visiting the local market and a few historic sites. Since I was making slow progress with my Amharic I was glad that he was conversational in English. As we rode, we joked around a little along the way. I intuitively felt that he was trustworthy. Because of this, rather than hail a new Bajaj off the street the following day, I decided to take his number and contact him directly for the next day’s excursion.

Early the next morning Daniel and I set off down a dusty road to the sounds of the rumbling engine beneath our feet and the occasional calls of children excitedly shouting hello as we passed. We quickly broke loose of the small city, tearing through scenic countryside at the Bajaj’s top speed of about 10 miles an hour. We were heading towards a crafts market just outside of town. Some local acquaintances recommended the market due to its mission to provide a source of income to struggling single mothers.

I began to make small talk with Daniel during the trip. It was then that I learned that the market was more than just a charitable initiative. It was also intended to continue the legacy of Ethiopian Jews from that region that had mostly fled the country after generations of persecution. While there weren’t too many left in the area, the single mothers that lived nearby to the ancestral home of Ethiopia’s Jewish population continued to produce crafts with the religious symbolism of its former inhabitants. Being of Jewish descent myself, I find the history of this unlikely subculture fascinating

Almost on a whim, I decided to ask Daniel how he feels about the Jewish religion. After recently listening to a tour guide recount how the Jews killed Jesus while referencing a passion of the Christ painting inside a nearby monastery, I wanted to gauge his reaction cautiously. I was relieved to discover that Daniel appeared completely indifferent on the subject. Since I was merely testing the waters, I didn’t offer my own opinion. I noticed that his rickshaw didn’t have any religious icons adorning the windshield. The thought crossed my mind that he might be in the overwhelmingly Christian nation’s slim and silent minority of non-believers, or even a covert Muslim.

As we rolled past thatch-roofed villages to the sound of the rickshaw’s purring motor, I found myself reflecting on all the new information I had learned about Ethiopian Jewry over the course of my trip, mainly from reading about it and speaking with locals. Unbeknownst to much of the western world, the Ethiopian Orthodox version of biblical history tells a radically different version of events than what is taught to any other denomination of Christians. In the bible’s Old Testament, there is a passage that briefly describes an exchange between the Queen of Sheba in ancient Ethiopia and King Solomon of the Hebrews. The Ethiopian Orthodox Christian interpretation of that story builds on that encounter with some surprising details.

In the Ethiopian version King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba became lovers. She converted to Judaism at around the time of the Apostles. The Queen later relinquished the crown to her son, Emperor Menelik I, and for hundreds of years thereafter an unbroken lineage of Ethiopian Emperors proudly claimed to be descended from King Solomon of the Hebrews. This tradition continued into modern times, right up until Ethiopia’s last emperor, Halie Selassie I, whose reign ended in 1930. According to the legend, Emperor Menelik returned to Jerusalem and brought back the Arc of the Covenant, along with many Jewish followers. This is why there has been a Jewish community in Ethiopia since Biblical times.

There is also a much stronger influence of Jewish religious practices on the Ethiopian Church than what’s accepted by other Christians. This includes adhering to Jewish dietary law and keeping the Sabbath. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church also maintains that the original Ark of the Covenant is kept in a church in Addis Ababa to this day. The powerful significance of the Ark is central to Ethiopian Christian’s religious beliefs. Replicas of the Ark, called Tabots, are kept inside every church and monastery.

The unusual similarity between Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Judaism hasn’t stopped the insidious influence of anti-Semitism from seeping into the culture and uprooting the lives of much of the country’s historic Jewish population. Known locally as Beta Israel, the distinctly African group of Jews faced racism at many points in Ethiopian history. Notably during the fascist Italian invasion of World War II and the oppressive communist Derg government of the 1970’s and 1980’s. Beta Israel are commonly referred to by the derogatory Amharic word Felasha, which translates roughly to landless wanderer. Over time the hardships facing Ethiopian Jews became so serious that several schemes were launched by the Israeli government to airlift them to Israel and grant them citizenship. That initiative was largely successful, and there are now far more Ethiopian Jews living in Israel than in Ethiopia itself. Today all that remains of Beta Israel’s once vibrant culture is a handful of ruins, some Jewish icons sold at the market, and a small number of timid survivors scattered across the northern region.

With all of this rolling around in my head, I stepped out of Daniel’s Bajaj onto the gravel and smiled at the weathered face of a hunched over elderly woman. She was clutching a few pieces of pottery in her hands adorned with the Star of David. I began negotiating with her, and rather than stay in the rickshaw Daniel stood off to the side and observed. He must have noticed my unabashed sympathy for the woman and excitement at seeing the pottery. I assume that he made the connection that my reaction was of a different quality than the average tourist’s response. While I was speaking with the woman Daniel came over to help me bargain. Whatever the reason, at that time he confided in me that his family is Jewish. I was blown away. I have read some estimates that put the population of Jews that remained in Ethiopia after the exodus to Israel as low as 0.015% of the total population. I, in turn, revealed my Jewish heritage to Daniel who seemed happy to hear it. We had established rare common ground in an unlikely place.

Daniel said a few words to the pottery vendor in Amharic, and before long she was ushering me off the street and down into a mud hut. To my astonishment the room was filled to the brim with the religious imagery of Judaism in the form of pottery. I couldn’t resist going on a shopping spree to support their endeavor. It is likely that her group of single mothers is among the Jews who were forced to convert to Christianity over the centuries to avoid persecution. There were clay menorahs meant for the Hanukah celebration, Lion of Judah statuettes, clay vessels used for ritualistic hand washing on the Sabbath, and even jewelry boxes engraved with an image of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon lying side by side. My purchases were followed by a cheerful tour of the facilities. I got a behind-the-scenes look at the kiln, loom, and pottery barn used to make the crafts. Just when I thought my day couldn’t get any better, Daniel invited me to his house for a traditional coffee ceremony. I readily agreed.

On the way back to Gondar the previous serenity of our journey was replaced by excited anticipation. I served Daniel with a volley of questions about his faith. He was not reserved. I learned that Daniel’s mother had been Jewish, as well as his maternal grandmother. Although seemingly trivial, these are actually important details. Jews generally believe that the Jewish soul can only be inherited from the mother. This means that if a non-Jewish man marries a Jewish woman their offspring are still believed to be completely Jewish. On the other hand if the child is from a Jewish man and a non-Jewish woman then this is not the case. Daniel confessed that although he is Jewish by birth, as an adult he hasn’t practiced the faith. He feels that he has to hide his identity because he said he wouldn’t feel safe if his heritage was widely known.

After chatting for the whole way back to the city we began to approach his house. The paved road became dirt and then the dirt road devolved into what is known as “African massage.” We arrived at his doorstep in what could be described as a shantytown. Just as I was beginning to feel sorry for Daniel, his one and a half year old son met us at the door. The tender look on their faces as they reunited eased some of my concern about his living conditions. Daniel was coming home to a loving family, and at the very least everyone appeared healthy and well fed. By my perception they seemed content, and to have at least a high enough standard of living to meet their basic needs.

I entered Daniel’s sparsely decorated , cluttered mud-walled house and was greeted warmly by his niece and their neighbor who happened to be inside. I would guess that the extra hands were needed to run the family general store or take care of Daniel’s mother-in-law, although it’s possible that they were expecting us. The cramped room I had just entered was dominated by a bed framed by hardened mud and covered with straw, which doubled as seating as we squeezed into the space. Directly across from the bed is a portal with no door that leads straight behind the counter of their compact general store. As my eyes adjusted to the dimly lit interior I noticed that in the house’s other room, further back, Daniel’s elderly mother-in-law reclined in a makeshift chair.

The family exchanged hurried words in Amharic and Daniel’s niece rushed to prepare the coffee. At the same time Daniel’s toddler, clearly well on his way to the terrible twos, began a rampage of destruction around the room. He was ushered tenderly from one pair of arms to the next, in a careful attempt to keep him away from coffee ceremony’s trappings being deployed on the ground in the room’s center. Ethiopia is the birthplace of coffee. It’s one of only a few locations where it’s a native species and it has grown wild long before being cultivated. Because of this, coffee has a long and venerated history as a cultural mainstay of the country and a source of profit through the ages. Coffee is not just drunk; it is imbibed in a traditional ceremony that’s a little more intricate than simply pushing the button on a Keurig.

In a matter of minutes, as I sat and watched, Daniel’s niece started a fire inside of a purpose-built piece of pottery, which ignited smoldering coals. To this she added a fragrant bark, which filled the room with the sweet smell of incense. She then took several handfuls of coffee beans, which looked as though they might have been freshly plucked from the field, and began roasting them by hand over the hot coals. As is customary, she went around the room with the sizzling pan so that everyone could smell the delicious aroma of the coffee as it was being prepared. It is also customary to serve food with the coffee, but in a quirky modern take on this practice many people have switched over to offering their guests popcorn, presumably because it is less of a financial burden and is easier to prepare. The coffee beans were then boiled in another embellished piece of pottery and were soon ready to serve.

As Daniel’s niece began pouring the espresso style delicacy into what resembled Chinese tea cups, her father dropped by to say hello. At that moment I picked up a knife with a blade like an arc that had been resting at the side of the bed. The handle looked like it had been welded by hand. I admired it aloud, and without hesitation Daniel offered it to me as a gift. It was a touching gesture, since from what I could see he didn’t have all that many material possessions. According to what I had read about the ceremony everyone is to be served three cups of coffee along with the popcorn. It is considered bad luck for a guest not to finish all three, and downright rude not to at least finish the first cup. This ceremony is often repeated two or three times a day even when there are no guests. To me this is sheer lunacy. By my estimation a single teacup of Ethiopian coffee is the equivalent of somewhere around two cups of American coffee in terms of potency. While that may be an exaggeration, I challenge any American to finish all three cups and maintain normalcy.

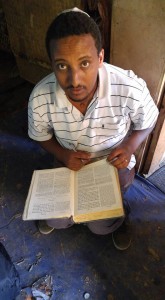

As I was sipping my way through my first cup Daniel slipped away wordlessly. He returned shortly thereafter with a copy of the Old Testament written in Hebrew and a few Yamakas. He proudly stated that these rarities were inherited from his mother. He handed me the Bible and asked if I would like to say a prayer. Like Daniel, I’m not an observant Jew, yet still consider myself Jewish due to my cultural and ethnic ties to the faith. I can’t read Hebrew and very rarely pray. Not wanting to disappoint, I made the appearance of carefully selecting a passage and then more or less picked a page at random and started reading the English translation aloud, hoping that Daniel would perceive this as prayer.

As I thumbed through the pages, I noticed that many passages had been underlined, and I tried to imagine by whom. I pictured Daniel’s mother hidden from view in a mud hut, sitting near a window and pouring over the words by candlelight, not daring to pray too loudly for fear of being discovered. For me it was a powerful visual representation of the faith that Daniel had inherited, whether he fully understood it or not. I asked him why he didn’t go to Israel when the other Ethiopian Jews fled. Daniel replied that he had wanted to very much, but at that time in order to get a visa he had to go through a rigorous process to verify his identity. Sadly Daniel’s mother passed away unexpectedly at a pivotal moment in the immigration process, which left him unable to complete it while most of the other Jews left the country. Daniel said that even now he would gladly go to Israel in search of better opportunities, knowing full well that he would have to leave his family behind. He said that as hard as it might be, earning money in Israel to send home to support them would be the best option.

I continued to sip the potent coffee as I let all of these revelations sink in. We moved into the house’s only other room and continued to make small talk as Daniel cooked up a quick dinner on the dirt floor right in front of me. It wasn’t until I got a good look at Daniel’s elderly mother-in-law that I realized why she hadn’t risen to greet us. She was almost completely blind with cataracts. I still attempted to communicate with her even though she couldn’t see me or understand anything I said to her. In a stroke of inspiration I held the luminously glowing screen of my smartphone to her face to see if she could make out some pictures I had taken with Daniel earlier in the day. My phone was far brighter than the weak lighting of the windowless room’s interior. She held the phone so close to her wizened face that it nearly touched her nose. She bathed in the artificial light and soaked in what was surely the clearest image she had seen in a long time. We both reveled in the moment of shared satisfaction. She poured over paintings from nearby churches that depicted biblical scenes one after the other with the iconic uniformity of cartoon reels. She examined each with deliberate focus, like a jeweler appraising diamonds. She even learned how to scroll through the pictures on her own, without my assistance. This was a woman in her 90’s that had most likely spent a good deal of her life living without electricity. I doubt she had ever seen a smartphone before and she might not see another. It was a proud moment for me.

Afterwards, we gathered together in the center of Daniel’s cozy hut-like room in appreciative silence. We were preoccupied with the orange-colored meal that we were all sharing. It was a spicy, bean based dish that was easy for Daniel to whip up in minutes using pre-ground dried bean paste. We ate out of a communal bowl, tearing off pieces of the spongy flatbread-like injera that lined the plate with our hands. Often the food placed atop the round injera is so colorful that its like eating off a painter’s palette. With only the right hand, we used pieces of injera to form bite sized sandwiches so that by the end our hands weren’t even dirty.

This was not the Africa of the “save the children” television ads, or the war-torn wasteland you see in the media. While Daniel’s family lived without the luxuries and excesses of the western world, they weren’t wallowing in depraved poverty either. There was a feeling in that room which is not always present in my own culture. It was a warm feeling, as we huddled there sharing a meal together. It felt like good will, like the fraternal drive to help one another along. It felt like community.