It’s not what you’re thinking. Although Part 1’s ending made for a great cliffhanger the gunman turned out to be nothing more than a security guard, however intimidating that might be. It did get me thinking though, as he escorted me up the rest of the trail towards the top of the mesa, about why an armed escort was necessary at all. A remote mountaintop monastery doesn’t exactly scream out security threat. Plus, the wall I had just scaled was the only way in. I mean come on; the place couldn’t have been more secure if it had a moat. Was I supposed to believe that he had to be armed to the teeth to protect me from rock climbing brigands? I started to wonder just exactly how close I was to the border of Eritrea, which I had intended to avoid. Before travelling to Ethiopia I had consulted with the U.S. State Department’s website for travel warnings and alerts, which is always a good idea for international travel. Front and center on the page is an advisory that in no uncertain terms warns U.S. citizens to avoid any and all travel to the border zone.

While the war between Eritrea and Ethiopia officially ended over a decade ago, skirmishes and troop deployments along the border continue to threaten stability in the region. Tourists who venture too close have recently been the targeted for kidnappings and murder. An attraction known as the Danakil Depression, not far from Axum, is especially volatile. The area hosts volcanic activity that creates surreal geographic features comparable to Yellowstone. It was always a must see destination, but has decreased in popularity in recent years due to the upswing in violence. Along my journey I have met some fellow travelers reckless enough to ignore the warnings just to see the Danakil Depression, but I had no intention of going anywhere near there myself. However incredible the Depression may be, it’s simply not worth risking my life to see. Despite my best intentions to steer clear of the conflict zone, as I studied the gruff features of the gunmen walking ahead of me somehow I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had been duped.

All of these thoughts were wiped from my mind quicker than an Etch A Sketch as we rounded the bend and arrived at the foot of the monastery’s outer walls. Upon reaching the mountain’s pinnacle upon which it’s poised I was suddenly faced with a sweeping expanse of views. A most welcome gust of wind swept across the summit, stopping the perspiration that had been set in motion by the relentless desert heat so fast that it left salt on my skin. I surveyed the panoramic view as if from the vantage of an eagle’s perch. The spectacular scenery alone would have been worth the effort of coming all that way, but the view was only one piece of my destination’s allure. On top of that were layers of historic and philosophical discovery.

What could have compelled those that commissioned the monastery to undertake such a feat? Was their motivation purely religious? When western religion came on the scene in Ethiopia, the local people must have had to reconcile their traditional animist beliefs with Christian values. I wondered if Christianity augmented those beliefs or completely displaced them. Could the mountaintops have been a spiritual center in the ages before Christianity took hold? Maybe the choice of location expresses a devotion to more than just Christianity. While I stood, reflecting on all of that, I couldn’t help but be overwhelmed by the breathtaking natural beauty. My surroundings were equally as impressive as the monastery I had come so far to see. The Ethiopian peoples’ age-old devotion to the Christian faith, as it was poignantly expressed where I stood, and the epic wilderness surrounding the monument were perfect companions. They have more in common than I would have realized. Both withstood the march of time so completely that to stand at their gates, as I had, one might think them immortal. The all-consuming advance of development and globalism and consumerism appeared to have had no effect on them whatsoever. These two giants, one physical and the other spiritual in nature, dominating my surroundings. These were elemental forces, pervasive and undeniable.

My ruminations may not beget definitive answers, but I trust they are productive in other ways. As I stood, all of those thoughts and more spun around my head faster than the birds dancing and darting through the air all around me. The path that spirituality takes through the hearts and minds of the local people was laid out before me. I never felt so connected to another culture as I did while following in the footsteps of a pilgrimage that has endured through the ages. I traced the history of every step with my mind’s eye as I went. My arduous journey to reach those doors was certainly the easiest it had been for literally ages.

After all of that pondering, it was time to take the next step and actually walk through the front gate. The courtyard of the monastery was as peaceful as a Zen garden. The wind that had so graciously cooled me moments before was relegated by high walls to the upper levels of the structure, where it gently whistled past rooftops. The noises that the wind elicited from the structure were the only sounds to be heard. Flags flapped and chimes jingled, doorways creaked and bells swung. The armed guard called upon a boy, who was the monastery’s lone watchmen, to go and fetch a monk to unlock the church.

With the boy gone it was just the two of us. We had whole place to ourselves. While waiting for the monk, the guard gestured silently for me to follow him. We walked back toward the outer wall, in the direction of a bell tower overlooking the entrance. It was all very medieval. We entered the base of the tower and climbed the stone steps in a spiral stairwell, that despite the ample daylight would have been pitch black if not for the occasional “window” that resembled an arrowslit in a castle turret. The top of the tower denoted the true high point of the mountain. It gave me a view of not only of the canyon below but also of the monastery itself and the surrounding ruins. The construction was fairly simple, with stone walls and a metal roof that had likely replaced less durable thatching. This upgrade was no doubt intended to carry the building into the next century, as preserved as past generations of Ethiopians have always kept it. I peered down from my post beside the swinging bells at the village surrounding the compound’s walls. It appeared to be abandoned on first glance, until the motion of a door swinging open caught my eye and I realized that monks still inhabit the low stone structures, whose crumbling facades looked like they could have been on display somewhere as relics from a long extinct culture.

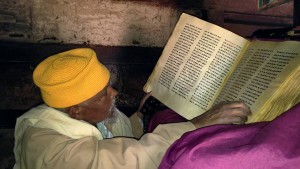

Once the monk finally arrived to unlock the temple at the heart of the monastery, I practically sprinted over from the bell tower, overcome with curiosity. Entering the temple itself was like stepping back in time. I took off my shoes and stepped over the threshold into what resembled a cavern. The ancient etchings, inscriptions, and paintings all around the small chamber came into focus as my eyes adjusted to the light. My surroundings seemed impervious to the passage of time, like prehistoric specimens trapped in amber. Watching the monk pray in the Ge’ez language of his ancestors upon a simple wooden platform was one final reminder of the implications of what I was seeing. People continue to reside at that humble monastery in isolated simplicity just as they did for hundreds upon hundreds of years. I was witnessing a contemporary link in an unbroken chain of countless monks who renounced their ties to society to pray at that very pulpit.

On the way back to Axum there were still more thoughts buzzing through my head about what I had just seen, more than would fit on this page. Through it all there was one nagging question that was left unanswered. “How far are we from the border?” I asked the driver. “Hmm… I think we are maybe 30 miles from there,” he answered in his best English. “What about the Danakil Depression? How far is that?” I pried. “Maybe 50 miles or more,” was his response. This was a mortifying thought. I was way too close for comfort to a dangerous and potentially lethal security situation.

It wasn’t until I got back to my hotel and talked it over with Shushay later that night that I learned the truth. “30 miles? Hah. More like 5 miles. That’s how close you were to the border. You can see all the way into Eritrea from where you came from. You even passed the site of the first battle with Italy after they invaded from that place,” Shushay said with amusement. “How can he tell you 30 miles? This is not right,” he added.

We were back at the same restaurant as the night before, only this time since it was a Friday night we expected some dancing. We were all drinking honey wine. I held the flask the way Simen taught me, which I was sure would impress them. “If you have all been friends for so long, then you must have embarrassing stories about each other. Let’s hear some stories,” I said, to spice things up. We all laughed as Shushay launched into an account of some recent dating mishaps. Then I noticed something. “Why the long face, Rasta? You don’t look happy,” I said. “Why is it that Shushay get all the girls? I just want one of them. Always he has too many girls. Maybe I can take one of his,” he stated sardonically. It turned out that Rasta was a virgin. Although in Ethiopia that isn’t so unusual for a 22 year old, he clearly wasn’t thrilled about it. “You see, my father was a soldier,” said Rasta. “We are strong in my family, but for the people in Axum it does not matter that we fight to protect them. They think we are low class. Soldiers have low status in our country. Maybe this is why it is so hard for me. Because I am the son of a soldier,” he said with a little more seriousness to his tone.

From what I have read, Ethiopia is unique in Africa in that in ancient times it had a hierarchic, caste-like structure that resembled medieval Europe much more than it did other African civilizations. Farmers, soldiers, and clerics functioned in separate and rigidly defined roles, with specific expectations of each. The divisions between classes were reinforced by the conception of morality at that time, so much so that it even seeped into the Amharic language. To this day some words used to describe farmers have negative connotations that are synonymous with words like uncouth. During times of war, soldiers traditionally lived off of what they could take by force from farmers. Those sorts of actions came to define their reputation as a class, and their moral standing in ancient Ethiopian society. I can’t be certain how much bearing that history has on modern times, but it seems that there is still somewhat of a stigma against soldiers.

“What about you, Ziggy? You’ve been awfully quiet about all this.” I prodded. “Ziggy don’t have our kind of problems,” Rasta answered for him. “He has family in America. His family take care of everything. All of his clothes are original. Look at his new t shirt. When we are out working every morning he is at home resting. But it’s okay. We love him anyway. It doesn’t matter to us that he has money. He is still one of us,” Shushay chimed in. Ziggy, who was a little on the shy side, didn’t have anything to add to that assessment. “Who wants to dance?” I said, and with that we were on our feet shoulder shrugging and chicken bobbing all over the dance floor.

As we were leaving the restaurant Shushay asked how many more days I would be travelling in Ethiopia. “Tonight is your last night?!” he exclaimed. “We have to celebrate.” With that began a raucous night on the town. Shushay seemed to know people at every bar and club that we went to. Rasta put on his army jacket and tried his best to impress the ladies, while Ziggy seemed more concerned with looking in the mirror than anything else. Contrary to what other travelers seem to expect at African clubs, I didn’t see a single prostitute anywhere. We danced and joked around worry free, and had a blast. When Shushay had too much to drink he let me drive his Bajaj home. We zigzagged through the streets with Shushay and I in the front, plus Ziggy and Rasta in the back squeezed in with two girls they had picked up at the bar.

The next day we headed back to the meeting tree to scope out a craft market. The whole place was teeming with busloads of tourists. After a while the crew hopped back in the Bajaj and took me to a local animal market just outside of town to check out the cows and bulls up for auction. This time I was the only faranji in sight, and would’ve been the whitest thing around if not for the sheep. Before taking me to the airport we all went out to a local pizza place, which was the best in town although not in the guidebook at all. The mood was a little somber, partly because I was leaving and also because we were still a little tired from the night before. As we were eating, the topic of conversation took a turn for the political, which was unusual considering that I wasn’t the one steering it. Rasta brought up the war with Eritrea. “Our country fights for what is right. Always we try to do the right thing,” he said patriotically, “but when there is war; Axum is not a safe place. You can hear the gun shots and the bombs from right where we are sitting. What we need now is peace. It is the bad governments that are doing this, not us. The people in Eritrea, they are family. We are all family,” he said. And deep down, I know that he meant it.