The night before my flight I said farewell to my new friend Simen. If you have been following my blog then you already know him as the sparker of many stories. His final advice for me was to keep my guard up in Axum. “Over there it is a much bigger city. Not everyone knows one another. People can do bad things and nobody knows who they are” warned Simen. “If you meet someone like me on the street that is very friendly, you must not trust them,” he added earnestly. It was touching that he was showing so much concern from my safety. “You don’t have to worry,” I said, “I can take care of myself.” It was hard to say goodbye. After so many adventures together, we had delved way below surface level and really gotten to know each other. “I will come back here again to visit you as soon as I can. Maybe by that time you will be a tour guide already, and I will be a teacher. Don’t worry, I’ll make it happen,” and as quickly as that I turned my back on Lalibela.

Early the next morning I walked onto the runway towards the small jet waiting to whisk me off to Axum, another ancient city in the mind boggling succession of Ethiopia’s wondrous historic sites. My first impression of Axum was that Simen was right to warn me not to trust it. The whole feel of the city was different. I could tell right away that it had a more dangerous edge to it. Even the touts seemed like they were a little slicker in their hustles. This time the talk of tour packages began before I set foot off the plane. As we were walking down the steps onto the runway of Axum a passenger that had been sitting a few rows behind me recognized me from the bar in Lalibela, the night I went dancing, and we struck up a conversation. He told me that he’s a tour guide and gave me his number, promising a discount off the normal faranji price.

Before leaving Lalibela I had called ahead to reserve a hotel in Axum, yet when I double-checked the guidebook on the plane I realized that the price I’d been quoted was $5 more than what it said in the book. ‘Hell no,’ I said to myself, ‘I’m not getting pushed around again by these guys.’ After arguing with the shuttle driver from the hotel I had called, who kept insisting that my online reservation was as binding as if it were written in stone, I took off with a different driver towards a more reasonable hotel. As soon as the portly driver I had taken off with opened his mouth he was already trying to hustle me. “I saw you talking with that man in the airport, ”he said, referring to the guide I had walked onto the runway with, “I want you to know, he is crazy. All the time he is trying to steal the tourists, but he is very bad guide. Completely crazy. Better that you stay away from this man,” he warned me. He glanced at me out of the corner of his eyes as he drove, with a look that spelled greed. Nothing about his statement was convincing. “My company is much bigger. We take good care of the tourists. Have many services. I will tell you about them…” he went on. I did my best to appear disinterested without being too rude, hoping he’d get the hint. Eventually I tuned him out entirely, and instead focused my attention out the bus window onto the curious new land I had arrived in.

Whereas Lalibela only had one main street in the downtown area, this city was laid out like a grid, with broad avenues left over from the Italian occupation. The streets were lined with all sorts of shops and restaurants that showed a level of sophistication well above the street peddlers I had become accustomed to dealing with. For all its grandeur, Axum was still far from what I would consider affluent. The wide, accommodating streets were home to little more than typical blue and white Bajaj, pedestrians, and the occasional mule train. Just when I was beginning to think of Axum as fairly similar to the other northern cities I’d been travelling in, we rounded the corner onto the block of my hotel just in time to see a camel waltzing down the street.

The same tout from the bus actually followed me into the hotel. As soon as I emerged from my room after putting down my bags he was there waiting in ambush, and immediately tried to pressure me into booking a trip with his company. I stoutly refused, and spent a good deal of time that day speaking with all the major tour companies trying to determine which tour would be most suitable and at the best rate. Following many of their recommendations, I decided that the following day I would take a day trip out of town to see an unusual monastery. It’s several hours away from Axum, known to be remote and difficult to access. Rooting out obscure monasteries had become a bit of an infatuation of mine by that point. Ever since my first Indiana Jones hidden temple experience in Lalibela I was hooked. On that trip, we entered the mouth of a vine-covered cave to explore an underground temple by headlamp, only to find the mummified remains of hundreds if not thousands of dead pilgrims stuffed into the recesses of the cave. They were so well preserved from the elements that some of them still had hair on their skulls. Feeling ready for anything, I toured the iconic obelisks at the heart of the city within walking distance of my budget hotel, in search of the next adventure.

Axum’s attractions are incredible in their own right, yet for me they were slightly overshadowed by the brilliance of Lalibela. It was as if I had never driven before, and was suddenly put behind the wheel of a race-car. Then, after racing the track, being given a luxury car to drive immediately after. Who can complain about driving a luxury car? It’s an extraordinary thing. When compared with a race-car, however, it loses some of the excitement of its appeal. Despite my ambivalence, I have to acknowledge that the obelisks of Axum are an unparalleled national treasure for Ethiopia with symbolic resonance. The stelae (obelisks) of Axum are regarded as the world’s highest monoliths. They memorialize a period of time when Africa was home to some of the most advanced and sophisticated civilizations in the world. I view the sites as a benchmark in African history that indicates past and future greatness. What’s more, The Kingdom of Aksum was able to complete this astounding feat of engineering in the 1st century, way ahead of their time. Touring the area is like walking through an ancient sculpture park of surreal dimensions. I walked around the obelisks with my head on a swivel, craning my neck to gaze up at the massive stone blocks balanced impossibly overhead. My stroll was interrupted only by the occasional jaunt through some of the subterranean crypts that dotted the site, where tombs were long ago discovered and relocated.

After an exhausting first day I started to head home. I took my time, stopping every now and again to soak it all in. Along the way I bought some bananas and sat on a bench at the confluence of what could have been a major roadway, but for lack of traffic. In the middle of the rotary, where I sat, was a gigantic tree giving shade to the peaceful scene beneath it. I had been told by a guide that the species of tree I was looking at is known locally as the meeting tree for its broad leaves and outstretched branches that give shade from the desert sun. That particular tree in the traffic circle certainly lived up to its name. There were kids playing table soccer, women selling baskets and bananas and drinks, and others chatting idly beneath its branches. The tree was so expansive that it seemed to reach even further than the roads whose spokes radiated outward from the circle’s center The plaza was a creation of the Italians during their brief occupation of Ethiopia. Their invasion had begun at the border not far from Axum, and so there was more residual evidence of their historic presence than in most other parts of the country. I sat for a moment and pondered what it would have looked like where I sat at the time of the occupation, as I ate my banana. I decided to get my boots shined for no particular reason, and sat down quietly in the shoeshine’s stall hoping that another camel would pass by so I could snag a picture.

I plopped down wearily in the seat, and almost immediately a local in his early twenties sat down at my side and introduced himself. “My name is Shushay” he said, extending a hand. He looked more stylishly urban then the people in Lalibela had, with an image-conscious tuft of curly hair protruding from the top of his head in a twist, and a little bit of hip hop style to his tight jeans and black hoodie. Despite these differences, there were no red flags to give credence to Simen’s warnings. While I was far from trusting of him, he came across as honest. “David, nice to meet you,” I replied, shaking his outstretched hand. I noticed a scar that bisected one of his bushy eyebrows. I wondered what the story was behind that, and yet my intuition still saw no reason to overreact. A boy quickly got to work on my trail worn boots. I sat immobilized as he began to chip away the dirt of many trails. Shushay had a captive audience. “What brings you to Axum? Where are you from?” he asked confidently. Still trying to size him up I replied, “Oh I’m just a tourist. I’ll be here for a couple of days to see the sights, that’s all. I’m from New York. What about you, where are you from?” I asked, not wanting to make any assumptions. “I am from a small village outside of Axum. I work here as Bajaj driver. If you want, maybe later I can take you to see the local sites. Here, take my number,” he said. That confirmed my suspicions. I didn’t think Shushay was dangerous, but I wasn’t so naïve as to suppose that he didn’t have an ulterior motive. I took his number and told him that I’d think about it, because there actually were some attractions that I didn’t get a chance to see that day with all the haggling in the morning to distract me. “I’ll be out of town tomorrow,” I said, “but there is one place in my guidebook that I couldn’t reach. You speak English well, so maybe you could do a better job finding this place than the last guy. I told that driver to take me to an address straight from the book, but he dropped me off outside a café instead.” We both laughed. “Don’t worry, I can take you anywhere in this city. I know where everything is. Just call me and I will come,” he boasted. I told him the name of the place I wanted to go and he assured me that it would be open late. I took his number and then stood up to leave. The shoeshine boy started demanding more money than I knew his service to be worth. Shushay said a few words to him in an unfamiliar language and he promptly lowered the price.

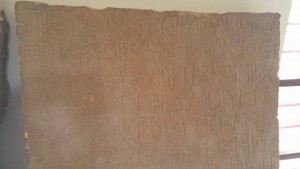

Later that evening, when I was back at my hotel, I meant to call to a local tour agency to make some final arrangements for the next day’s tour but I ended up dialing Shushay by mistake. True to his word he was outside the hotel’s door practically by the time I hung up the phone. “Can you still take me to see some of the historic sites, or is it too late?” I asked. “Don’t worry, it is not too late. I will show you,” he replied. A short time later we arrived at the same café I had been dropped off at earlier by the other driver. I was puzzled. Both drivers read the address to the monument right out of the guidebook, so why did they keep taking me to the wrong place? “I think you don’t understand. Here, follow me,” said Shushay as he escorted me into the café. “Let me see your book,” he said while taking the guidebook from my hands, “I will be your guide.” As it turns out the ruins are actually located inside the café’s courtyard. Talk about living history. There must be so many ruins around the city that if the government tried to make them all off limits there’d be no room for anyone else. The main attraction of the café’s exhibition was a stone tablet protected by an enclosed shed behind the seating area. Each surface of the rectangular, tombstone-shaped tablet jutting mysteriously from the earth was inscribed with writing from different alphabets. Several biblical languages were represented such as ancient Greek and Latin, alongside the Ge’ez language from the Abyssinian civilization that preceded modern Ethiopia. It was astonishing to see such a pristine relic in the back of a café that didn’t even look particularly popular. The artifact clearly belonged in a museum. As we walked further along down the café’s property, there was another much taller obelisk that had been wrapped inexpertly with cheap Christmas lights as decoration. I shook my head in bemused disbelief.

I was willing to give Shushay the benefit of the doubt that the whole thing was a bit of a confusion rather than a deliberate attempt by him to drum up business. “Look, if you want to go back I understand. I can take you no extra charge,” he said apologetically. He went on, “Or we can go to another place. I know one more place like this.” I didn’t come to Ethiopia to retreat back to my hotel at the first sign that things weren’t going my way. I decided to press on to the next site. By that time it was getting late, and I wasn’t sure if the next place would even be open. When we arrived to the small archaeological park the gate was locked and the guard had gone home. Shushay asked around, and it turned out that the guard’s young son, who was busy playing soccer with his friends nearby, had the key after all.

The boy let us in, and I insisted that he join us on the pretext that he might be able to point out something interesting. I also brought him along because I didn’t want to be alone with Shushay in the park. I didn’t feel threatened by him, but it seemed like a wise precaution to take since the whole thing was a little risky to begin with. We scoped out a few crypts, and ended up on a little knoll overlooking the city center. I asked Shushay to take a picture of me with my smartphone, confident that I could chase him down if he tried to pull anything. Handing a stranger my phone while alone in a park at dusk might not have been my finest judgment, but that small gesture was an instant turning point for us. I think we both felt the tacit trust implied by the action. The pictures saved on that phone alone were worth more to me than the phone itself, but it could easily be worth a month’s wages to him or more. He looked me in the eyes as he took the phone from my hand, and then snapped a few photos. Soon we were on our way.

Later that night I had dinner plans with an American of Ethiopian descent and her brother. I had met them on the plane from Lalibela as well. In the airport we had agreed to meet that evening at a restaurant that was suggested by the so-called “crazy guide” who had been part of the conversation on that flight. He said that the restaurants in the guidebook were no good, and told us about what they call a culture house where traditional food is accompanied by live music and folk dancing. The only problem is that the number that the girl from the plane had given me to reach them wasn’t working. Since my phone couldn’t make calls I was using one that I borrowed from a hotel attendant. It’s possible that just as I couldn’t call a local number, maybe the local phones I was using couldn’t dial an American number. In any case, a little disheartened, I decided to go to the restaurant to see if I might run into them. When I walked outside who was waiting outside my hotel but Shushay, who’s Bajaj was parked on the corner right out front, possibly by coincidence.

When I arrived to the restaurant the place was packed with a lively mix of locals and tourists, mostly in large groups. It was an interesting venue. Both the walls and high ceilings were decorated with all sorts of cultural symbols. There were flags and colorful baskets adorning each wall, and musical instruments of varying sizes dangling by strings overhead. The room was as broad as a dance hall with ample space between the giant circular baskets which dotted the venue in place of tables. I walked around slowly, scanning for familiar faces. I didn’t spot them inside, so I moved out to the patio just to be sure. Still no luck. Sitting alone without so much as a book to keep me company amidst such a festive crowd was a grim prospect. I started looking for seats in secluded corners. As I walked back into the building I internally debated calling another taxi to eat somewhere quieter. To my surprise as I came in from the patio I ran right into Shushay sitting down to dinner at one of the baskets with two friends. We spotted each other at the same time, and he waved me over with an easygoing smile. “David! Come and sit with us, don’t worry we will share our food with you,” he said generously. It was the fourth time I had run into him that day. I graciously agreed. He introduced me to his friends, “This is Arre and Zerabruck.” We shook hands. I didn’t think I would ever get their names. “Arre is said like Taf-ari in Rastafari,” said Arre. “I always listen to reggae music, and some time ago I even had long hair. Maybe that will help you remember,” he added, sensing my confusion. Eventually I would come to call them Rasta and Ziggy.

Everything about that night was impressive to me. Even the basket we were eating out of was incredible, not to mention the food. Once I got a closer look I realized that even though it was large enough to replace a table it was obviously hand made. The dish that was eventually placed on top of it was larger than a pizza pie and entirely covered by a thin flat piece of injera bread. The top of the basket was the same size as the large plate we were served on, which was much lower than a table, allowing us to gather in close right over the food. Over the injera was placed small portions of stewed meat, vegetables, and bean dishes all uniquely spiced in a variety of colors. The presentation was so well orchestrated that it looked to me like edible art. We literally tore into the dish, ripping pieces of injera off of whatever part of the circular bread was closest to us and using it to scoop up bite size pieces to sample each little mound of food in turn.

As we ate I asked them as many questions as I could between bites. “So how long have you guys been friends?” I asked. “For a very long time,” answered Shushay, “I am from the village, but as long as I have been living here I have known them. It has been maybe seven years now.” I learned a lot from them that night. For instance, the people of Axum speak a totally different language from the rest of the people I’d met. While Amharic is still spoken, Axum is in the northern region of Tigrai and so the people there speak Tigrinya, which sounds a lot more like Arabic due to the regional influence of Yemen and the Sudan. That was disappointing news. I had just begun to get a grasp of Amharic, learning the numbers one through ten and a few words of vocabulary. Now I’d have to start all over with Tigrinya.

The most unexpected thing I learned was that the people of Axum have a lot more in common with the Eritreans than I would have thought, considering that the nearby border has been the site of rampant violence in recent years. Eritrea and Ethiopia first started fighting over control of territory in a war that lasted from 1998-2000. What started as border skirmishes soon degenerated into what must have been one of the most unnecessary wars of the 21st century. Most battles were fought over territory on a more ideological level than practical. The land wasn’t economically significant or of notable strategic value. According to Wikipedia: “While Eritrea and Ethiopia, two of the world’s poorest countries, spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the war and suffered tens of thousands of casualties as a direct consequence of the conflict, only minor border changes resulted.”

Yet somehow, despite tension between the two nations which continues to this day, I had just met three Ethiopians from the region hardest hit by the conflict that all seemed sympathetic to the Eritreans. Judging from the tone of our conversation, none of my new acquaintances seem to harbor any ill will towards Eritrea. It turns out that all three of them have family there, mostly distant cousins. This is apparently not unusual in Axum. For Tigraians, families that have been separated by a few miles, an artificial line, and endless propaganda have much more in common than what stands between them. In fact for a long time both countries were unified under the same flag. Many people that currently live in Axum are originally from Eritrea. They came seeking work and then were unable to return due to the war. After an enthralling conversation, the three amigos insisted on paying for my dinner despite my protests. We made plans to meet again when I was to return from the next day’s tour. It was a great night.

The following morning I was up at the crack of dawn and ready to begin my journey. After such arduous negotiations over the trip, I shouldn’t have been surprised to find that the “4×4” I had been promised was actually a dilapidated death trap that looked to be significantly older than me and with the scars to prove it. The windshield was badly cracked and one of the brake lights had been shattered. I should’ve known better than to trust those touts. After some heated discussion to get me going that morning, I eventually persuaded them to send a van instead. I found it to be in passable condition, so off I went into the unknown.

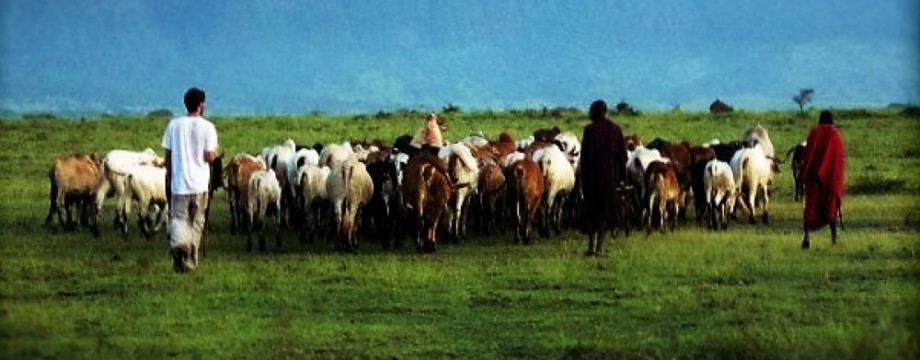

This was going to be the tour that all of the guides had been raving about. We had a road trip of several hours ahead of us as we made our way towards a monastery. The driver didn’t speak much English, so it was up to me to figure out what exactly I would be looking at. At least nobody would try to sell me anything. The ride was relaxing, and before I knew it we had reached our destination. The driver parked in a sandy unpaved lot at the far end of a small village, facing a mountainous canyon. The terrain had become more and more desolate as the drive went on. Now that we had stopped it was clear that we had entered a full-fledged desert. All around us the canyon was painted in hues of orange and red. With no trees in the way there was an unobstructed view straight to the top of the mesa that the driver was pointing to. Off in the distance, following the driver’s upward gestures, I could spot a white speck that I assumed to be my destination. I was looking forward to the challenging hike up to the monastery, although it was a little puzzling that for such a highly recommended attraction we were the only people around.

Once I started walking I caught sight of a series of weathered old stone steps. They looked to be so old that I’m sure people had been climbing them long before America was even “discovered”. I climbed and climbed, past another small village and occasionally shaded from the brutal sun by huge cacti of a species I had never seen before. Just when I thought the steps would never end the trail came to a halt abruptly. I stood at the base of a sheer 30 foot cliff towering overhead, scratching my head. ‘Well that’s odd’ I thought, ‘How am I supposed to get around this?’ As I approached the foot of the cliff, a monk who had been sitting by the wayside rose to greet me. He didn’t speak a word of English, but in his hand was a piece of rawhide leather that he kept holding out for me to take. The leather strap formed a sort of crude rope. He was holding the loose end while the rest dangled above from the top of the cliff. Confused, I followed the makeshift rope up with my eyes and at that moment another monk popped his head out from a nook near the top holding another piece of leather rope formed into a loop. Understanding dawned on me. ‘You’ve got to be kidding,’ I said to myself. Other than the three of us there was nobody within sight, and from that vantage point I could see quite a lot. ‘Well, I’ve come this far, so here it goes,’ I concluded. The monk at the top lowered the loop of leather down to me. I slung it over my head and fastened it around my waste. I let go of the “harness” and then grabbed the other piece of leather with both hands in a white-knuckled grip. It was thicker than a regular rope would be. I couldn’t fully close my fingers around it when I tried to grip it. Also, it was disturbingly oily, and had a pungent smell to it of whatever animal it had come from. I noticed all of this and decided to press forward, fearing that if I hesitated too long I might change my mind.

I began scaling the wall slowly and carefully, walking each foot up with baby steps before reaching for more rope with my hands. The monk at the top assisted me by pulling at the rope I was wearing as a harness. I tried to encourage myself by imagining how the monastery was built. If workers could somehow hoist themselves and all the materials up the cliff reliably enough to build an entire structure up there, then surely I could climb the wall too. Despite my efforts to talk myself up it was a nerve wracking experience, but after a few tense minutes I made it to the top without issue. The nook that I had reached was just below the top, and although I couldn’t see it from the bottom I noticed right away that the trail continued around the side of the mountain at a gradual slope like one long switchback. Another thing that I noticed immediately, which couldn’t be seen from the bottom, was a man holding an AK-47 assault rifle standing just behind the monk that had been hidden from view.

To be continued…