By the second day in Lalibela, my manic dash to visit every major historic site that the city had to offer was complete. With such limited time remaining and the creeping sensation that I might never see anything like Lalibela again in my lifetime, I was loathe to even pause for breath. As soon as the tour was over I began pestering the guide to find out what other excursions I could squeeze into my time there.

Simen, after the previous night’s unexpected adventures, was sympathetic to my cause. Being the only student in his Taekwondo class who is going into the tourism industry, and thus the student with the best English language skills, he had been by my side the whole night translating my every word. With such a tremendous difference between the English and Amharic language, if it hadn’t been for Simen I might as well have been an orangutan up there trying to communicate with them because there’s no way they’d understand anything. I’d imagine there was a certain amount of prestige in it for Simen. Making a public appearance with a faranji, the local word for foreigner, was a spectacle that couldn’t have been bad for his social standing. Maybe he felt like he owed me something, or maybe that’s my own faranji cynicism and he was simply making a kind gesture. Whatever the reason, when Simen overheard me asking the guide about what was left to do in the small town after checking every box on my bucket list of holy sites, he quickly jumped in with his own input.

Simen pulled me aside and asked if I would like to go for a hike with him early the next morning. He said he knew of a monastery high up in the mountains that’s accessible from the city but would take the better part of a day to reach. I readily agreed. I knew that he was being generous, and that any other guide would charge a lot of money for such a trip.

Bound by a determination to see the most distinguished historic sites in Ethiopia, up until then I had been religiously adhering to the guidebook’s recommendations. I was travelling along a proverbial tourist superhighway of the country’s most trafficked northern cities. I leapt at the opportunity to venture off the beaten path straight into the mountainous wilderness I had been staring at longingly through the windows of buses for weeks.

The next morning I awoke before dawn with a smile on my face. Somehow Simen had managed to get up even earlier and traveled to meet me in the lobby of my hotel. We shared a hearty cup of black espresso and broke bread just as the sun began to peek over the mountaintops. Within minutes we were on our feet and ready to go. We wound our way upwards through the city’s narrow streets and alleys with the strength of Ethiopian coffee, half winded as we haltingly exchanged formalities, pausing occasionally to suck in breaths of the thin mountain air. Before we even began our ascent we were already at an elevation of 8,600 feet within the city limits. As we climbed the hilly streets, a group of young students in their uniforms passed us on their way to school. Some of them called out my name as we passed. They shouted out greetings in English and Amharic, “Salaamne, David. Are you fine?” They must have recognized me from the Taekwondo class the night before. I was thrilled.

Keeping a militant pace, we marched right out of the city and into the surrounding foothills. We didn’t so much as pause to catch our breath until we had climbed so high that we’d already reached a cliff’s edge commanding views of the city below. Simen pointed out the schoolhouse where our class was held the night before, which was already surprisingly far off in the distance. From where we stood it looked about as small as the hawks flying high overhead. He also tried to show me his house, but each one was indistinguishable from the next and he eventually gave up. A soon as we caught our breath we soldiered on, but his comments from moments before had piqued my curiosity. Who did Simen live with? Did he live with his family, roommates, or alone? What about siblings? Feeling much more alert with the morning sun shining on my back, I began to warm up both literally and conversationally.

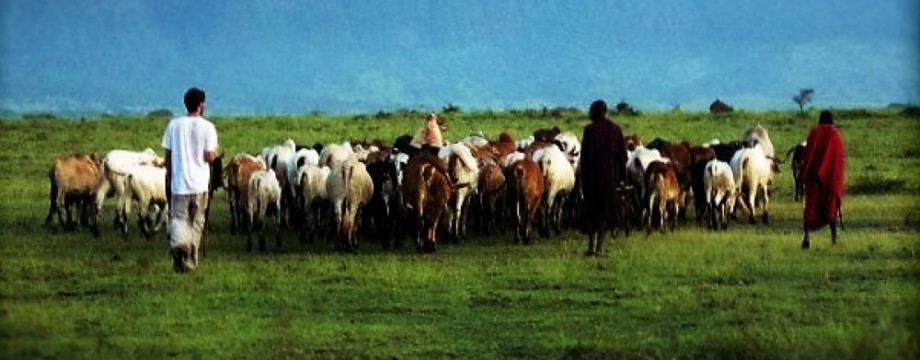

I asked Simen all of those questions and more. As new vistas unfolded the higher we trekked, so too did the story of Simen’s short 17 year old life unfurl as I plied him with questions. I learned that Simen was born and raised on his family’s farm about 50 miles outside of town. To be clear, the whole region is desert, semi-desert, or tundra higher up. Sagebrush and cacti dot the landscape as well as groves of Eucalyptus trees, a non-native species that was imported by Europeans centuries ago. While the region is mountainous, it isn’t as green as one might imagine mountains to be. In fact, we weren’t too many miles from South Sudan to the north or Somalia to the east. It surely isn’t an easy place to be a farmer. Simen told me that he’s the youngest of 4 siblings. He has two older sisters and a brother closer in age.

Once I got him talking, the story of his journey to find a new life in Lalibela moved faster than the landscape. Simen started working on the family farm when he was just 7 years old. At that time he would help out any way he could with small tasks and chores. As he got older and took on more responsibility, Simen and his older brother hatched a plot to break free of the backbreaking labor of the farm life. They couldn’t wait to leave it all behind. Their ambition was to continue their education and pursue it to the best of their abilities, which could only mean moving to Lalibela. Although to me, having grown up in New York, Lalibela is a tiny city that is really little more than a large town. For Simen and his brother, coming from the most rural of country backgrounds, Lalibela was as big a city as they had ever known. Relocating there was an intimidating prospect for them.

Simen recalled how it all went down. His parents weren’t completely thrilled at the idea of their sons leaving. They could have used the extra hands on the farm, but there was also hope that the boys would send money back for them so they weren’t completely against the move either. The fact that Simen and his brother couldn’t afford transportation to the city on their own was their first hurdle. His family’s farm is approximately the same distance from the city as the free shuttle my hotel had provided for me from the airport when I had first arrived there. That thought put things in perspective for me. As I imagined them stranded on the farm I couldn’t help but feel a little guilty.

After some time Simen and his brother were able to convince a local acquaintance with a vehicle to let them hitch a ride with him free of charge. Simen’s parents wanted to help their sons out, but they didn’t have any money to give them. Instead they gave their boys a bundle of tef to sell at the market. Tef is a type of grain found only in Ethiopia. It is used to make injera which is a spongy flat-bread found in practically every meal and used as a sort of substitute for utensils. People place the thin round injera over the top of the plate, covering it. The custom is to tear off small pieces of injera and scoop up bite sized portions of the food with their hands to make little sandwiches. Injera is filling, delicious, and extremely nutritious. It’s especially high in protein and iron. Simen and his brother bravely ventured out on their own with little more than a bundle of tef to their name. Somehow in their naive excitement they left the tef in the car after they were dropped off and it was lost to them.

As we trekked ever higher into the mountains Simen did his best to describe what life was like for him in such a new and unfamiliar environment. Needless to say losing their tef was a major setback. That was all they had brought to support themselves until they could establish some independence. Despite the loss, the country boys resolved not to give up their dream. When they first arrived they were out on the streets, strangers, nearly penniless. Since Simen’s brother was older and physically larger he was able to find work as a porter doing manual labor. Simen had no choice but to go into the shoe shining business. Eventually he earned enough money, one coin at a time, to afford his own shoeshine box. The two brothers have been steadily progressing ever since.

At times Simen didn’t have enough money to pay his school dues. He was a diligent student and always maintained good grades, so when times were tough he was able to plead with the headmaster to make allowances for him. Simen also told me that he is grateful for the help of his aunt, his only relative in Lalibela. She is an elderly nun who lives in a spare room that her landlord charitably rents her at a discount. Simen used to occasionally pitch in to help her pay the rent when he could. I asked how much and he told me it’s about 320 birr a month, which equals about $15. When he stayed with her the two of them had to share the tight quarters which were barely adequate for one person alone. His bed was a few bales of hay lined up in a row covered by a blanket. Sometimes, when he was lucky and his aunt could afford it, she would also provide him with meals.

Now that the hard times are behind him, Simen shares a room with his brother at their own place. While they still have a long way to go to accomplish their dreams, Simen is optimistic that things will continue getting easier. I asked Simen how often he visits his parents and sisters on the farm, but he admitted that he doesn’t make the trip too often. Judging from Simen’s tone, he seems to resent them. He complained that his parents didn’t support him financially when he needed them, yet that didn’t stop them from pressuring him to take care of them. He also resents the fact that with their traditional, chauvinistic values his parents refused to allow his sisters to receive a formal education because they are female.

I knew we were nearing the top of our climb when I could see birds soaring below us instead of above. My legs burned with each of the final stone steps as my lungs labored to pull in the crisp morning air and absorb what little oxygen was available with each breath. Having already seen a myriad of monasteries over the course of my journey, I was expecting the hike to be more of a highlight than the destination itself. When we finally reached the monastery perched high above the city, it took my breath away like no hike ever could. Not only was the aesthetic of it astonishing, but it didn’t seem humanly possible. How could a civilization with such rudimentary technology ever construct such a thing in the remotest of places over such inhospitable terrain?

Like the churches far below us, this monastery was carved much the same. The structure was chiseled from a single titanic boulder like the masterpiece of a gigantic sculptor. It was rendered from the earth itself, painstakingly excavated and crafted with a stubborn determination that must have consumed the life force of countless laborers. The monolithic structure is fused by all points to the ground below. While this particular monastery is significantly smaller than the main attractions of Lalibela and simpler in design, it is difficult to fathom how and why it is set in such a location.

Other than a few devout monks inhabiting the area, Simen and I had the place all to ourselves. We were greeted at the summit not only by the main attraction, but also by 360 degree views of mostly uninhabited wilderness all around us. Lalibela was but a colorful speck in the distance, as brilliant as a single point in a night’s sky filled with exotic constellations, as orienting as the Southern Cross. After soaking it all in for a long while I was ready to head back. Just as I started to turn around, Simen asked, “Would you like to continue to another monastery?” with a mischievous grin on his face. ‘What? Are you serious?’ I thought. “It’s only another half hour or so from here” he chimed in. If you have been following my other journal entries, then you would know that Simen loves springing these kinds of things on me. “Of course I would,” I replied with all the enthusiasm I could muster. After the previous night’s sparring match with a Taekwondo black belt I was more tired than I’d like to admit.

Just as I thought we had reached the zenith of our day we climbed even higher, seemingly seeking out the roof of Lalibela. As I struggled to follow at Simen’s heels, he suddenly veered off the trail and began to scramble upwards with his hands and feet, dodging cacti and loose rocks as he went. I had little choice but to follow him, although leaving the narrow trail made me a little uneasy. Towards the end we were trekking at such a steep pitch that we were practically bouldering, but without a safety net. I tried not to look down. At one point we reached a ridge so steep that someone had constructed a makeshift ladder to climb it. It was just a few flimsy branches of eucalyptus nailed together in a crisscross pattern. I let Simen go first.

Just when it seemed the view couldn’t get any better, we reached the top. The real top this time. Every other mountain in view was now beneath us. We had arrived at a wide plateau of a mountaintop as flat as a table. Somehow, compared to the rocky outcropping we had scaled or even the solid ground beneath that, this mesa was as lush as a spring meadow. It was almost surreal, like we had entered an enchanted forest. There was shin high grass blowing in a gentle breeze. Even though it was the dry season, all of the shrubs were flowering. They were dotted with yellow blossoms like out of some kind of fairy tale. At the far end of the meadow was a still more improbable monastery. This one was at least built of wood and metal or I would have been pinching myself.

As we approached we were greeted by a solitary nun who seemed uncharacteristically happy to see us. Simen and the nun began speaking in Amharic, which was incomprehensible to me. After a moment Simen grinned as he turned to face me. “She says that other than one tourist on Christmas you are the only faranji that has been here in many months. In a very long time,” he said proudly. Lalibela is famous for their Christmas celebration, and annually hosts up to 50,000 people each year at Christmastime. Taking that into account I felt that the nun’s statement was really saying something. What we had done that day was unforgettable for me, yet surprisingly it was even meaningful for the locals.

I asked the nun if she wouldn’t mind posing for a few photos, to which she graciously obliged but not before covering her entire body in a shawl. Simen reminded me that the nuns here lived a spartan lifestyle. They survived on meager rations and the kindness of others. The woman I was speaking with most likely stayed up there on the isolated mountaintop to maintain the monastery. She didn’t ask for anything, but I pulled out my wallet anyway and gave her a tip for being willing to pose for photos. “You have done a great thing,” was Simen’s response as we walked away. I felt that I was gaining his confidence. We began our descent in high spirits. It was a lot to accomplish in a day before lunch time. As we began our descent he said, “Would you like to visit my auntie?”

To be continued…