Procyon Lotor As observed and studied on the Evergreen State College campus and in the Evergreen Forest

The North American Common Raccoon, also referred to as the North American Raccoon, Common Raccoon, Northern Raccoon, or colloquially as coon is a mammal species originally native to the North American continent. The Raccoon is the largest of the procyonidae family, a family within the suborder caniformia, that consists of nocturnal, ring-tailed, plantigrade placental mammals.

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Procyonidae |

| Genus: | Procyon |

| Species: | Procyon Lotor |

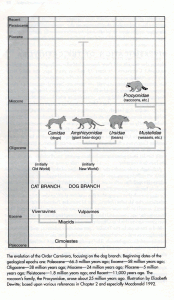

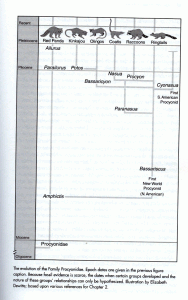

On the left is an evolutionary tree showing the development of the Procyonidea family. It illustrates how the Carnivora family branched out into the cat and dog sides, with the dog side splitting into three smaller families, one of which was the Mustelidae, from which the Procyonidae latter grew out of. The tree to the right shows a more detailed break-down of the Procyonidae family and how it developed and split into distinct species, including the raccoon.

Distribution

The Raccoon is originally native to North American and at present there are 26 different types of raccoons living across the North American continent, ranging from Canada to Panama. However, while the raccoon may have been native to North America it has since spread across the world. Raccoon populations have been recorded existing throughout countries in Europe (the largest abundance being located in Germany) as well as around the western end of Russia and parts of China and Japan. The spread of the raccoon across the Atlantic began as early as Columbus’ voyage to the Americas and continued in the centuries to follow. The explorers saw the local raccoons and thought they would either make interesting pets or be useful for later scientific study, but when they brought the raccoons back to their home countries in Europe most of the raccoons escaped easily and began spreading across the new territory. This process was made easier by the fact that raccoons are very adaptable animals and can flourish even in an urban environment. They are one of the species that has adapted with relative ease to human encroachment and urban spread. The two large factors that have enabled this easy adaptation to human environments are habitat requirements and diet (both of which will be discussed at greater length further on).

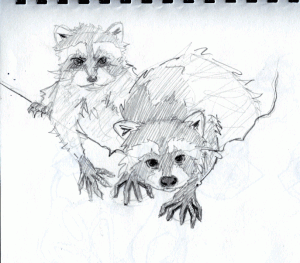

Morphology

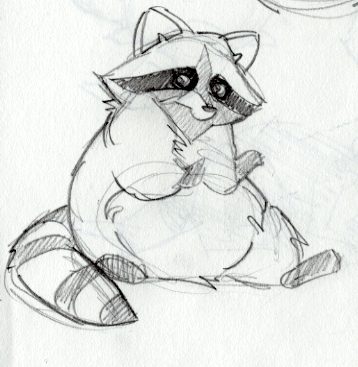

Raccoons are one of the most variably sized mammals, but on average a raccoon will measure between 16 and 28 inches from head to hindquarters (not including their tail, which usually measures between 8 and 16 inches with the average being 10 in). The weight of an adult raccoon varies widely, being both dependent on habitat (and associated feeding habits) as well as season (they gain winter fat). In addition, male raccoons are on average 15-20% heavier than their female counterparts. (Zeveloff, p.58)

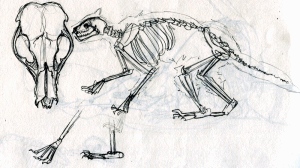

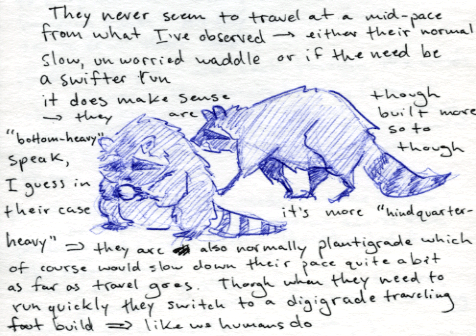

Raccoons are built with relatively compact torsos, accompanied by shorter limbs in comparison. Their locomotion is generally considered plantigrade, though they are capable of digitigrade locomotion should the need arise. Due to the fact that they are built on shorter limbs with a heavier, compact torso, coupled with their full-footed walk means that they move with a distinctive waddle. They are not easily frightened from what I’ve observed (though they remain healthfully cautious) so the slower shuffling-waddle pace they move at is the right speed for them, allowing them to continue moving to their next destination while allowing them to forage as they go. However, that isn’t to say that they can’t move at higher speeds. If the need arises, be it danger in the form of predators or humans or the need to avoid weather, they are capable of shifting up onto their toes and scurrying at a relatively fast pace. This flexibility in stance greatly increases their ability to avoid dangers and puts them in a smaller category of animals that are able to change from plantigrade to digitigrade and back at will, including humans.

The other interesting ability they possess in regards to their feet is the ability to turn their hinds feet completely around. Due to the fact that raccoons are one of the largest species to engage in head-first decent when climbing, they have developed the ability to turn their hind feet around 180 degrees so that they can grip better and use their claws for braking.

Below are notes I took on raccoon locomotion while observing them:

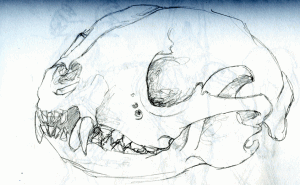

Raccoons posses all of the normal skeletal structures of the average mammal without having any extreme anomalies. Raccoons are part of the group of placental mammals that possess a baculum or “penis bone”, a bone running the length of the penis that aids in reproduction. A raccoon’s baculum averages about 4 inches long, making it one of the longest baculum in proportion to body size. In a number of Native American cultures raccoon baculums were worn as charms for luck or fertility.

Another physical trait that stands out in raccoons is tactile sensitivity. They have paws that are built rather similarly to a human hand, including having the innermost digit on both hands set down the side of the palm like a human thumb. On top of their excellent dexterity, they possess heightened sensitivity in their paws that gives them a sense of touch beyond most animals, humans included. In fact, nearly two-thirds of the raccoon’s area for sensory perception in their cerebral cortex is specialized just for the interpretation of tactile impulses received (more than any other animal that has been studied). This means that the majority of information a raccoon receives about a given object is through touch, which is why they participate in the activity called “dousing” (which I will explain shortly in conjunction with diet).

Diet

Raccoons have an extremely flexible diet as far as other animals are concerned. They are omnivores and will eat nearly anything (though they still have their favorites). They find food through multiple means, including gathering, hunting, and scavenging. They eat a variety of vegetation, including leaves, berries, nuts and fruit, as well as the occasional fungi as well. They are also adept hunters, eating a wide variety of other animals as well. They eat mainly invertebrates (roughly 40% of their diet), but will eat most other animals they can catch, including fish, amphibians, crustaceans, small birds, mice, and more.

Through my observations I found that even over the span of a single evening both the raccoons’ foraging method and their consumed food was spread. In a single evening they ate scraps from the housing dumpster, caught crawfish in a stream, ate worms, caught mice, and munched on leaves. Raccoons truly are the ultimate omnivores.

As mentioned earlier, raccoons engaged in the practice known as “dousing” when they eat. Due to the fact that raccoons have such high tactile sensitivity, they can gain better information about an object, and quicker, through touch rather than sight or smell. This is why raccoons will roll their food around in their hands, sometimes not even looking at it, before they decide to eat it. They “see” through their hands. Now “dousing” is the practice of dunking food into water before eating it, sometimes dunking the object multiple times before consumption. Most people see this behavior and assume that the raccoon is washing off or cleaning their food before they eat it, however this is not the case. Raccoons dunk their food in water before they eat it in order to feel it better, not wash it. The important part is that when they dunk the food their hands get wet, which heightens their tactile sensitivity even further, and as discussed before raccoons are all about the sense of touch.

Social Behavior

Raccoons are social animals that live near each other and operate in groups for most of the year. They live and forage together in loosely constructed units, usually consisting between 5 and 10 individuals depending on the time of year and age of the individuals ( the particular clan I observed consisted of 6 members). Most groups consist mainly of related females with a related male or two, the ranks further filling out with juveniles that have yet to branch off on their own completely. However, occasionally, non-related males may form a small unit of no more than four to protect against foreign males during mating season.

During my observation I noted that while the group did appear to live together and participated in activities as a group, there was still a level of individuality maintained; there was a balance of group and individual. The raccoons would be moving through the woods foraging, each waddling along on their own quest for food, yet they would still be traveling in loose formation and they would still communicate warnings or excitement.

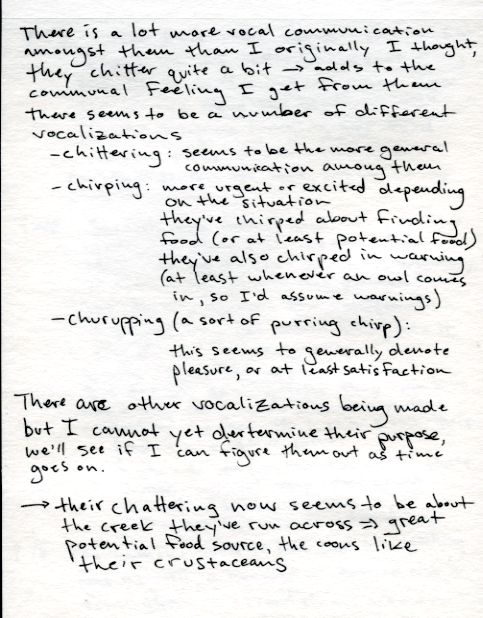

As just previously mentioned, raccoons communicate, and they communicate often. Overall, they turned out to be much more vocal than I had originally anticipated and it was surprising to hear all the different chittering and chirping between them. Raccoons possess the ability to make a wide range in sounds (though seven of the thirteen identified vocal calls are only used in communication between a mother and her kits) and they use vocalization to express all kinds of things including excitement, frustration, agitation and sadness.

Below are some notes on the three different vocalizations I was able to pick out during my observations:

Reproduction and Development

For the average North American raccoon the mating season is from January through March, peaking in February (though the exact timeframe tends to fluctuate depending on the local climate). Raccoons engage in polygyny, commonly having a single male mate with two or three females during a season, though the number of females a male mates with can vary depending on the density of the population. Though the males will defend their mates from other males seeking to mate with them, the actual birth and initial raising of the young is an only female activity.

A female raccoon’s pregnancy typically lasts about 63-65 days, though outliers going either direction have been reported before. Most female raccoons will have one litter per year (though rare occurrences of two a year do sometimes happen) and while yearling females are capable of mating, most females who bear kits are at least a couple years old. Before giving birth, beginning several days prior to the actual event, the female will seclude herself in her den. During this period she will not nest, though she may gnaw off wood and bark chunks to line the den a little better. The mother will give birth ranging from 1-8 kits, though the average is usually 2-5 depending on the location. The newborns are small, weighing about 2.1-2.6 ounces and measuring about 4 inches from crown to rump. They are born with there eyes closed and their ears sealed, both will usually open within 21 days of birth, though sometimes it can take up to a month. They are born with fur over every surface except their bellies, though neither the mask nor tail rings are more than hinted at (both will fill in completely by the end of the second week). The mother will typically remain with her newborn kits for the first night or two, and then for the next few weeks limit her foraging activity so as not to leave her offspring for too long.

The young raccoons will normally start walking between four to six weeks, and by the end of the seventh week they can usually run and climb relatively well. During sometime between the tenth and twelfth week the young will begin accompanying their mother on her foraging trips at night. At the beginning they will go a short ways with her for a little while before heading back to the den, but as they grow older they stay out with her longer and longer until they are comfortable enough to forage on their own.

The average raccoon will not reach full growth until the end of it’s second year, though this is given to fluctuate depending on the region. The juveniles will typically leave near or with their mother until this two year mark, at which time they will usually set up on their own (though many don’t set up their territories far from their mother, the males typically wandering farther however). (Zeveloff, p.124-127)

(3) Pictured is the popular video-game and comic character Sly Cooper, along with his cohorts in crime. Sly has been one of the more prominent raccoon characters in media recently and has done nothing to change the raccoon's image in the public eye. He is a world-famous master thief according to the game's lore, and the goal of the game is to solve various puzzles and steal valuable commodities and artifacts. While Sly is painted as "stealing for the greater good", and a guy who takes care of his friends, ultimately he follows the normal raccoon depiction of being a trickster and a thief.

Cultural

Name Origin:

The name “Raccoon” has been originally linked to Captain John Smith, of Native American princess Pocahontas fame. His first spelling has been recorded as being “rahaughcums”, his attempt at writing down the words spoken by the local Algonquins. It is more likely however, that they were pronouncing the word “arakunem” (which translates from Algonquin as “he who scratches with his hands”). It is surmised that the settlers began using raccoon after they derived it from “arakun” a shortened version of “arakunem”. (Zeveloff, p. 168)

The Raccoons Reputation:

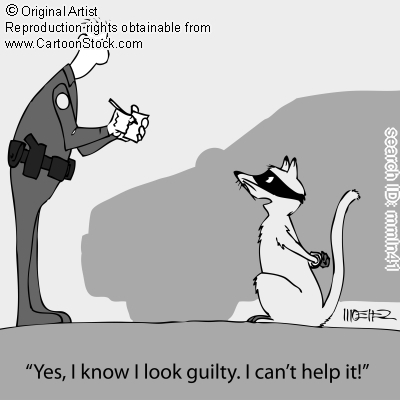

Throughout multiple cultures the raccoon has come to fill one of two roles; the master thief or the cuddly companion. Because of the raccoon’s facial markings, or “mask”, it has been portrayed consistently as the trickster character, or thieving little scoundrel. There are tons of tales of raccoon thievery in Native American lore; tales of how raccoon got his mask, how raccoon got his stripes, how raccoon became the marked forest-dweller. All of these tales involve the raccoon being a thief. Some times he dons the mask himself to steal something, but is forced to leave it on as punishment. In another version the raccoon puts on a mask to scare the raven and the bear, but he is so successful at scaring them that they forget who he is and he becomes stuck with the mask forever. The common thread in all of these tales though is that the raccoon is tricky. He steals from people, frightens people, tricks others into stealing things for him. Regardless of the exact tale the raccoon is painted as the thieving, tricky half-villain. This is not only true from one tale to the next, but from one culture to the next. The raccoon has been universally labeled as a thief, and that stereotype still exists today. Raccoons are still portrayed as bandits and thieves in all types of media in our present day, it has become their normal persona in the public eye.

However, sometimes there is a rare exception to the thief label, a second portrayal. The other role the raccoon occasionally gets to fill is the cuddly sidekick. In a number of stories a raccoon appears as a silly, cute and cuddly companion for the main or other major characters. For example, Meeko the raccoon, Pocahontas’ silly sidekick is a prime display of the cuddly raccoon portrayal. As in the picture to the right, their proportions are made more infantile and their expressions softened in order to raise their appeal with audiences.

The problem with both these portrayals, however, is that neither are accurate. They are both extreme incarnations of specific attributes that the raccoon possesses. While raccoons may be very intelligent and very adept at stealing what they desire, they are not the smirking cartoonish villain they are often portrayed to be. They may also be smaller and cuddly looking sometimes, but they are never the air-headed fuzzballs that they are sometimes described or shown as. In my opinion, they are made up of all the best qualities of both portrayals; they are intelligent and crafty, managing to get what they need through ingenuity, yet they are also capable of being cute and fuzzy now and again.

Here are a number of different images of raccoons to serve as examples of how the thieving trickster stereotype and scavenging mischief-maker images are perpetuated:

Shuffling, shimmering, film noire bandit,

body patterned of linear shapes of black and grey,

fading with age though the mask always stays.

Nimble fingers to pry open any potential prey,

be it nuts, berries, small animals, or a bag of Lays.

Funky feet turned backward for their face first descents,

Seeming oddly clumsy yet climbing with finesse.

Tails not prehensile, yet not made of simply fluff,

something in-between, perhaps just fuzzy and big enough,

though their ears perhaps fall in a similar debate, pointy versus round,

yet I know not how it matters, but it must be important somehow.

Moving easily in day or night, though the later is the norm,

the moon their guide, the stars their map, guiding them as they explore.

Preferring cover of some kind,

concrete or natural it does not matter,

though based on where they choose to sleep one could assume the latter.

Undeterred from their quests by humans of any kind,

they ignore people and seem only annoyed when you get in their way,

though in the end I don’t know how much they actually mind.

poem by Tyler Strenk

In this short animation I created different visions of the raccoon in motion 🙂

Bibliography:

Zeveloff, Samuel I. Raccoons: A Natural History. Washington D.C: Smithsonian

Institution, 2002. Print.

Penn, Audrey. Chester Raccoon and the Acorn Full of Memories. China: Tanglewood

Publishing Inc, 2009. Print.

Rosatte, Rick, Ryckman, Mark, Ing, Karen, Proceviat, Sarah, Allan, Mike, Bruce, Laura,

Donovan, Dennis, Davies, J Chris. “Density, movements, and survival of raccoons in Ontario, Canada: implications for disease spread and management.” Journal of Mammalogy, 91(1): 122-135, 2010. Print.

Beasley, J.C, Rhodes, O.E. “Influence of patch- and landscape-level attributes on the movement behavior of raccoons in agriculturally fragmented landscapes.” Canadian Journal of Zoology, Research Press: 161-169, 2011. Print

Susan E. White, Phyllis K. Kennedy, Michael L. Kennedy, “Temporal Genetic Variation in the Raccoon, Procyon lotor.” Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 79, No. 3 (Aug., 1998), pp. 747-754

Lotze, Joerg-Henner Sydney Anderson. “Procyon lotor.” Mammalian Species, No. 119, Procyon lotor (Jun. 8, 1979), pp. 1-8

Kennedy, Michael L, Lindsay, Stephen L. “Morphologic Variation in the Raccoon, Procyon lotor, and Its Relationship to Genic and Environmental Variation.” Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 65, No. 2 (May, 1984), pp. 195-205

Randle, Martha Champion.“The Waugh Collection of Iroquois Folktales.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 97, No. 5 (Oct. 30, 1953), pp. 611-633

McAllester, David P. “Riddles and Other Verbal Play among the Comanches.” The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 77, No. 305 (Jul. – Sep., 1964), pp. 251-257

Image Citation

(1) Dewitte, Elizabeth. The Evolution of the Order Carnivora.

Zeveloff, Samuel I. Raccoons: A Natural History. Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2002. Print.

(2) Dewitte, Elizabeth. The Evolution of the Family Procyonidae.

Zeveloff, Samuel I. Raccoons: A Natural History. Washington D.C: Smithsonian Institution, 2002. Print.

(3) Sucker Punch and Sony Computer Entertainment America. “Cooper Gang”. August 12, 2007. Wikipedia. May 16, 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Copper-gang.png.

(4) Sucker Punch and Sony Computer Entertainment America. Title unknown. May 16 2012. The Guardian. May 16, 2012.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/gamesblog/2012/may/16/sly-cooper-thieves-in-time-preview

(5) Moeller, M. “Raccoon Cartoon 9”. Cartoonstock.com. May 17, 2012.

http://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/r/raccoon.asp

(6) Luna689. “Oh hai. We’re here to help you”. August 13, 2008. icanhascheezburger.com.

May 17, 2012. http://icanhascheezburger.com/2008/08/13/funny-pictures-to-help-you-take-out-the-trash/