fiber from angora goats.

Author: allkat24

Skirting

removing edges of fleece.

“Improved” Sheep

fleece shedding genes have been suppressed – have a white coat, are even in staple type from tip to tail, and fleece grows continuously.

Medullated

fiber with a hollow core.

Notable Concept – Cottage Industries

Week 5 marks the halfway point of the quarter and my research in this area, so I have decided to create an informative post on one of the most notable concepts that I have come across in these past few weeks of research; that concept being cottage industries.

Cottage industries are defined as “an industry whose labor force consists of family units or individuals working at home with their own equipment” (Merriam-Webster). Over the course of my research, I have realized that almost all of the business models that I have directed my attention to fall along the lines of this definition and it has become a point of interest in my search for a sustainable and ethical form of textile production.

I began by looking at khadi cotton and its role amongst the unemployed peoples of India. Khadi is, by nature, a movement rooted in the spirit of the cottage industry. Traditionally and historically, all textiles in India were khadi until British textile mills and colonization began to shift focus away from local industry. Because of this, its role in the Swadeshi movement was pivotal to its survival and in many ways to the survival of the craftsman who participated in the industry. The focus of this movement was to provide employment to the many people who could not find employment. Particularly for those who did not have the ability to move out of rural areas to find jobs in factories. Khadi gave people the opportunity to have a source of income that was entirely self-driven and involved very little resources to create. This craft only requires self-powered machinery and the raw materials used for spinning and weaving, so there is very little investment that the craftsperson has to make initially to get started. Khadi’s association with freedom from colonization and support of craftspeople who have no other source of income has created a market that sustains those cottage industries and allows people to have options other than working in inhumane conditions.

A continent away, a similar industry arose in both Ireland and Scotland. There is an incredible parallel between the island people of these nations and the traditional crafts that received international attention. For the people of the Hebrides (Scots-Gaelic speaking islands off of the Northwest coast of Scotland) it was Harris Tweed, and for the people of the Aran Islands (Irish speaking islands off of counties Clare and Galway, Ireland) it was Aran knit sweaters. These two crafts began like most folk crafts have; necessity for survival and protection from the elements. Tweed was created to utilize as many different materials as possible and Aran jumpers (or “ganseys”) to protect fisherman from the harsh sea wind.

What was particularly interesting to me was that both of these crafts were not brought into the attention of the fashion industry by the people who were involved with the traditional production of the garments. Instead, in both instances (and in the case of khadi cotton as well), an “outsider,” usually someone of a more privileged socio-economic status was responsible for recognizing the economic potential of the craft and proceeded to create a business and market for the craft. In the case of Harris Tweed it was the

landlords of the land where the tweed originated that pushed for the marketing and sale of tweed and for the case of Aran sweaters, it was anglo-Irish protestants who were largely responsible for bringing the attention of the outside world to the crafts of the island people.

It is hard to know for sure whether the a genuine concern for the well-being of the island people of these nations. In the case of Scotland, there is an irrefutable link between the financial success of the locals of the Hebrides and that of their landlords. However, it cannot be denied that the emergence of the craft market did drastically change the lives of people who previously relied on sustenance farming and fishing as a way of survival. I do believe in a lot of ways, it was beneficial to have people from outside the island way of life involved in the production of their crafts. Without people who knew how to navigate the world of business and law, it would have been much more difficult for the crafts to be protected under trademarks that ensured the crafts stayed relatively close to the original “cottage” structure while facilitating enough growth to provide employment opportunities to many different members of the local community.

After learning all of this information, it was very special for me to be able to visit Olympic Yarn and Fiber – a modern day example of a cottage industry. The owner, Lynn started the business herself, invested in the machinery herself, and runs the business out of her garage by herself. This to me is the perfect example

of traditional cottage industry concepts blended with the high productivity of modern day mechanization. Because Lynn was able to purchase machinery that allows her to process more fiber than one in the traditional industry could dream, she has the ability to provide for herself and her family in a way that those employing traditional methods could only dream of in an entirely local and community-supported manner.

Because Lynn is only in her first few years of business, she is not able to provide employment for anyone in the community yet. But it is a goal of hers and I am very eager to see how the business progresses and continues to be pillar of local textiles and community sustainability.

Spinning From the Beginning – Week One

On Monday evening I attended my first class on wool spinning at Arbutus Folk School. To start the class, we went over the basics of protein fibers and discussed the various different methods of processing and prepping the fibers for spinning. This being my first time actually interacting with wool and a drop spindle, I was actually incredibly surprised by how much knowledge I had retained from the reading I have been doing on the subject over the past couple of weeks.

I did, however, learn quite a few new concepts that I will list here:

- When spinning, there are two different kinds of spinning techniques: the “Z Twist” and the “S Twist” (Basically clockwise and counter clockwise)

- When plying, you must spin in the opposite direction that the wool was spun in

- When buying “roving” (cleaned and carded wool) you should look for fiber that has a staple of at least 3 inches, anything less than that probably is not worth your money

- Good fleece makes a “ping” noise when you hold it up to your ear and tug

- Just like humans, wool producing animals exhibit health issues in their fleece, so an animal that has undergone a hard winter, pregnancy, stress, etc will have sections that break when tugged

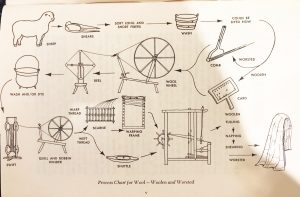

We then went through the life cycle of wool and what steps need to be taken in order to create spun wool most efficiently. This is exhibited in the diagram Emily showed us from the book “Textile Tools of Colonial Homes”

Finally, we got to spinning our first wool. We began by “pre-drafting” the roving we were given. We did this by gently pulling the roving apart in order to create a thinner, longer piece. This is done in order to make the spinning process go a bit quicker and smoothing.

After that, the act of spinning itself was actually surprisingly intuitive. It was comprised of using the drop spindle as sort of weight that lead the twist and pinching of the roving at certain points in order to control the width of the wool. I’m really pleased with my first attempt at spinning:

At the end of class, we were given some roving to practice with and the homework assignment to spin 4 nights out of the week and to spin all of the materials we were sent home with. Next week we’ll learn how to ply our yarn so that we can have a finished product.

Week 4

This past week, I tried as much as possible to focus on the wool industry and I believe I was able to stay focused on that topic pretty successfully given just how much there is to study.

I began the week by visiting Olympic Yarn and Fiber (a detailed post about that visit can be found here). This was the perfect way to begin a week of intensive wool studying as I was able to witness the wool processing procedure in person and was incredibly helpful during the rest of the week while I was trying to piece together an understanding of an incredibly vast and diverse subject. From a business perspective, it was interesting to see a modern day “cottage industry” that still utilizes modern day technology.

To me, it is absolutely mind blowing how much work is required to process fleece into a modern day garment and even more staggering still how much work was poured into processing and crafting wool textiles without the use of machinery. As I continue to gain a more in depth understanding of the various different stages in the lifecycle of a garment, it has become more than obvious that industrialization was the key to fashion for the sake of aesthetics rather than functionality and durability. Without machines to see out the processes for us, there is no conceivable way that we could have the surplus that we do now.

It has also struck me that in many ways, mechanization symbolizes a loss of consciousness when it comes to textiles. Before textile mills began to pop up across the globe, textiles were localized in a way that I think many of us cannot quite understand. In many cultures, sheep were from local pastures, having gradually adapted to the environment and climate of a given place, the fleece spun and knitted by mothers who knew the sheep well, looking to keep their children, husbands, and loved ones warm and protected from the elements (I could write a whole new post about the gender roles associated with wool crafts, which I will likely do before this study is over). Don’t get me wrong, I am in no way glorifying the need to engage in hours of tedious spinning and knitting as a way of survival. However, I do believe there is something to be said for a crafter knowing where their materials are from and having a connection to where the finished product is going – Olympic Yarn and Fiber is an example of a modern day model of a similar structure.

I continue to have a love/hate relationship with what I know to be true about the industrialization of textiles and this past week of study has done nothing to polarize either of those feelings. It has incredible to read about how survival crafts have evolved into lucrative businesses for peoples who have had little options in the past, but at the same time the impact of other forms of industrialized crafts continue to leave me with pause before celebration the various different ‘advancements’ of humankind.

Restoring Ancient Grains Seminar Ticket

“Only in the past century, as wheat squeezed through a genetic bottleneck of uniformity of flour blends intended for mass-produced breads, has the wealth of wheat biodiversity been forgotten.” (Rogosa, p. 24)

“Just as today the organic farmer understands we need to nourish the soil and the earthworms in order for the earth to to be fertile, the ancient Israelis not only enriched the soil with animal waste, compost, ash, dried blood, fallowing, and crop rotations but believed that it was necessary to feed the people in order for the earth to be fruitful. Ancient Israelites believed that soil fertility was based on food justice.” (Rogosa, p. 131).

It has been a long time since it was a secret that our food systems are monopolized by big names, that the supply chain is not sustainable, and that the methods of production focus on profitability rather than nutrition and environmental responsibility. However, Restoring Ancient Grains by Eli Rogosa goes far beyond what has made its way into the minds of the average consumer and explores just how deeply the wounds of mono-cropping and genetic modification have become over the last century.

As a student of plant fibers and textiles, when Rogosa states that “only in the past century, as wheat squeezed through a genetic bottleneck of uniformity of flour blends intended for mass-produced breads, has the wealth of wheat biodiversity been forgotten.” (Rogosa, p. 24) and continues to tell the tale of the complications that have arisen from a market that has become globalized and dependent on an array of fertilizers, pesticides, and fungicides, it sounds all too familiar to the countless studies done on modern day cotton crops. Similarly, the way the industry has adapted to the mechanization of bread production sounds eerily similar to the way the clothing industry has adapted to industrialized textile creation.

While reading Restoring Ancient Grains, I was made aware of just how vast the amount of wild (and domesticated) varieties of wheat are edible and suitable for baking with. But perhaps more importantly, I was made aware of how hardy the wild varieties can be and of how different species have evolved to fit certain climates thanks to traditional farmers and seed savers. This makes me wonder if the global use of G. Herbaceum cotton for textiles is something that should be re-examined and if there are not more “wild” alternatives to the sustainable fashion industry.

Interestingly enough, when Rogosa says to “follow the money” in order to see where our food systems have gone wrong, the rest of the book shows that when you look where the money is lacking, you find centuries of survivors who have adapted with their surroundings and have used the plants that were available to them instead of being able to afford imported goods. In the same way that you had rural farmers saving the seeds of landrace wheats to bake into traditional cuisine, Swedish peasants learned how to create fabric from nettle (known as “the peasant’s linen”) that grew abundantly nearby because they could not afford the heavily imported linen garments of the upper class.

Because landrace wheats were not bred to be mono-cropped or mass produced, it is much harder to manage them in an industrialized manner. You cannot rely on machines to knead them and you certainly cannot pack breads baked with this wheat into shipping containers and expect them to last the journey over to a different continent. This is yet another parallel to the issues we are seeing in today’s textiles. Instead of being made meticulously by hand to last for ages, they are made to fall apart in order to sustain the worldwide demand for new trends.

Rogosa takes our modern day issues with globalized crops to a very spiritual place. She states that “just as today the organic farmer understands we need to nourish the soil and the earthworms in order for the earth to to be fertile, the ancient Israelis not only enriched the soil with animal waste, compost, ash, dried blood, fallowing, and crop rotations but believed that it was necessary to feed the people in order for the earth to be fruitful. Ancient Isrealites believed that soil fertility was based on food justice.” (Rogosa, p. 131). Looking at the contrast between ancient ideas of agriculture and the modern day industry has led me to ponder on these aspects of the wheat industry. As with the rest of my research into the agriculture involved with textile production, it once again brings me back to weigh the pros and cons of globalization, and if there is any way to truly find a balance between mankind’s ingenuity and an understanding of the land and plants that we are working with and rely on so heavily.

Visit to Olympic Yarn & Fiber

Today I had the privilege of visiting Lynn at Olympic Yarn & Fiber and getting the opportunity to ask her questions about her process and business. She was incredibly helpful and happy to talk about her convictions as a small business owner as well as to share her extensive knowledge of fiber processing.

We went through her mill and she walked us through each of the steps that she takes to process animal fibers.

First, she scours the fleece to clean it and lets it sit out to dry. Here’s a photo of some Suri fleece after being scoured:

Then, the wool is place in the picking machine which straightens out the fibers and loosens them up.

A video of the picking machine in action:

A photo of the contrast between pre-picking wool and post-picking (the one on the left went through the picker):

Next, the wool is placed in the carding machine to separate and straighten the fibers (unfortunately I wasn’t able to get a video of the carding machine as it wasn’t in use)

After carding, the wool is sent through the drafting machine to turn the wool into a continuous line of fiber

A video of the drafting machine:

Wool after going through the drafting machine:

Finally, the wool is placed on the spinner to be spun onto spools

A video of Lynn setting up the spinner:

And here’s what the finished two-ply yarn looked like:

Overall, it was very helpful for me to see the mechanized process all the way through. After weeks now of reading about the history of spinning and its evolution from hand processing and spinning, I was really pleased to have the opportunity to see just how efficient industrialized processing is.

More importantly, having the opportunity to talk to Lynn about her views on sustainability and locality was pretty eye-opening. She described her business has “cottage-esque,” meaning that it is a family-run business operating from home, but it still utilizes modern day advances when proven to fit in with her idea of sustainability. Lynne explained that she believes strongly in having family businesses that fill the role of specific tasks that a community needs done – her place is to process both her own fiber and that from others.

This was an interesting idea for me since oftentimes the only time I’ve seen business models that utilize heavy machinery are ones that also rely heavily on importing and exporting their products. Visiting Olympic Yarn & Fiber, however, helped me to see that mechanization does not necessarily have to mean globalization, just as efficiency doesn’t necessarily have to mean profit over quality.

Week 3

During this past week, I tried to focus on researching the origin of certain well-known folk crafts. I made some very interesting connections between the arts and crafts movement throughout different societies as well as discovered a few stark contrasts.

I am most excited about discovering the origins of Harris Tweed and how it affected the people of the Hebrides and the textile economy of Scotland as a whole. Interestingly enough, I was pointed towards this history while reading a section on the Gandhian Khadi movement in India. Gandhi cited the Duchess of Sutherlands generosity in giving people of the Hebrides spinning wheels in order to provide them with some form of economic stability.

I found some writings by Angus MacLeod, a native of the island of Lewis in the Hebrides, where he detailed the early history of tweed, it’s evolution into Harris Tweed, and the growth of demand and production. It seems that tweed was a textile common among the West of both Ireland and Scotland; it was simply the fabric that people made out of what they had. It wasn’t until around the famine of 1846 that tweed was promoted as a good for exportation. As demand for tweed grew, the landowners of the parish continued to push for mills, trademarks, and an overall wider range of production for the good. Upon reading further on the subject and having a bit of background knowledge on the landlord/tenant relationship of Scotland, I have a slight hunch that the ‘generosity’ of the good Duchess as well as the rest of the promoters of the craft may have been a bit more self-serving.

MacLeod writes that oftentimes the islanders were too poor to pay merchants in monetary currency and that they would trade agriculture for rights to inhabit a certain plot of land. To me, it makes sense that the island landlords would do what was in their power to ensure that their tenants were producing profit in any form they could. It also presents a situation were tenants could easily be taken advantage of. I am unsure of how much documentation of the exact economics of the trade there is, but I can see an easy opportunity for the landlords to demand tweed as payment for rent, and then upcharge it due to the trademarking and high demand. This is going to be something I plan to continue looking into until I can hopefully determine exactly who was benefitting the most off of the growth of the industry.

I did notice a theme while looking into this subject – survivors of native cultures living in remote areas, usually the last native language speakers of a certain colonized piece of land, practiced folk crafts as part of their everyday lives. Eventually, a member of the upper class “outside” world would notice the intricacy of the craft and see an opportunity for business. In Scotland, it was British landowners, in Ireland it was protestant academics, and in Ecuador it was Western tourists. Each culture seems to have a different history in the way that they conduct business, however it’s pretty intriguing to see that they have a similar start.

Next week I will be looking at wool and wool crafts specifically, so I hope to look further into how they’ve been used and marketed throughout history.