Like (and even more so) with the colonized British Isles, I will not be able to cover Indian dress in its entirety, and have instead chosen to focus on one particular region. I’ve just to speak about Rajasthan specifically because a great deal of modern day textiles and apparel come out of the state. Similarly, many elements of Rajasthan’s traditional dress have made their way into the global fashion market – with or without credit.

Because of India’s history of occupation and Rajasthan’s particular geographical location, the dress traditions have been subject to a good deal of outside influence. Even so, Rajasthan and its many different people’s has retained its indigenous textiles and beliefs associated with it. Even today with Rajasthan being the home to acres upon acres of cotton fields and garment factories for Western clothing, the Indian state retains a unique cultural identity that both evolves with changing times and retains elements of dress that are important to the society.

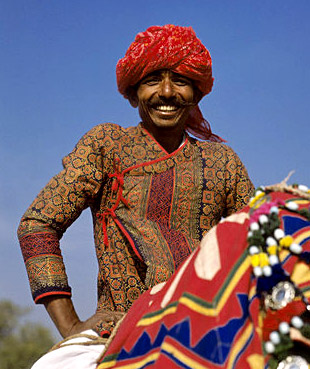

Perhaps the most globally known aspect of Rajasthani dress is the kurta. Traditionally, this long, knee length tunic is worn by men and can often be found made of khadi. This specific garment is not specific to Rajasthan. In fact, it can be found worn all over the west of Asia. There are, however, specific designs and materials that make kurtas specific to the state of Rajasthan. A specific “type” of kurta is the angrakha. The name of this garment is derived from a Sanskrit word meaning “body shield.” Once again, this garment is traditionally worn by men. Color is a significant part of these garments and are often dyed using the traditional method of “tie and dye” (the very technique that we in the Western world now associate with the 60’s and 70’s).

Historically, these garments were hand spun, woven, and dyed and worn for occasions of significance. Today, they are produced on a large scale and can be purchased at incredibly low prices. Modern fashion has seen the transformation of kurtas from traditional men’s wear to dress that is most commonly seen on women – this trend has held particular sway over the Western world of fashion. This shift could be a result of Western ideas of masculinity and femininity, with the vibrant patterns and fitting trim of the kurta subscribing more to the later. Now, kurtas, or close reproductions, can be found in just about any fast fashion store.

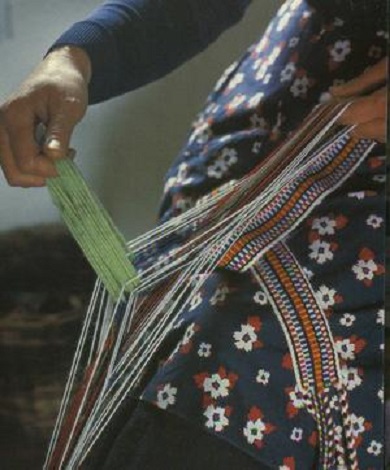

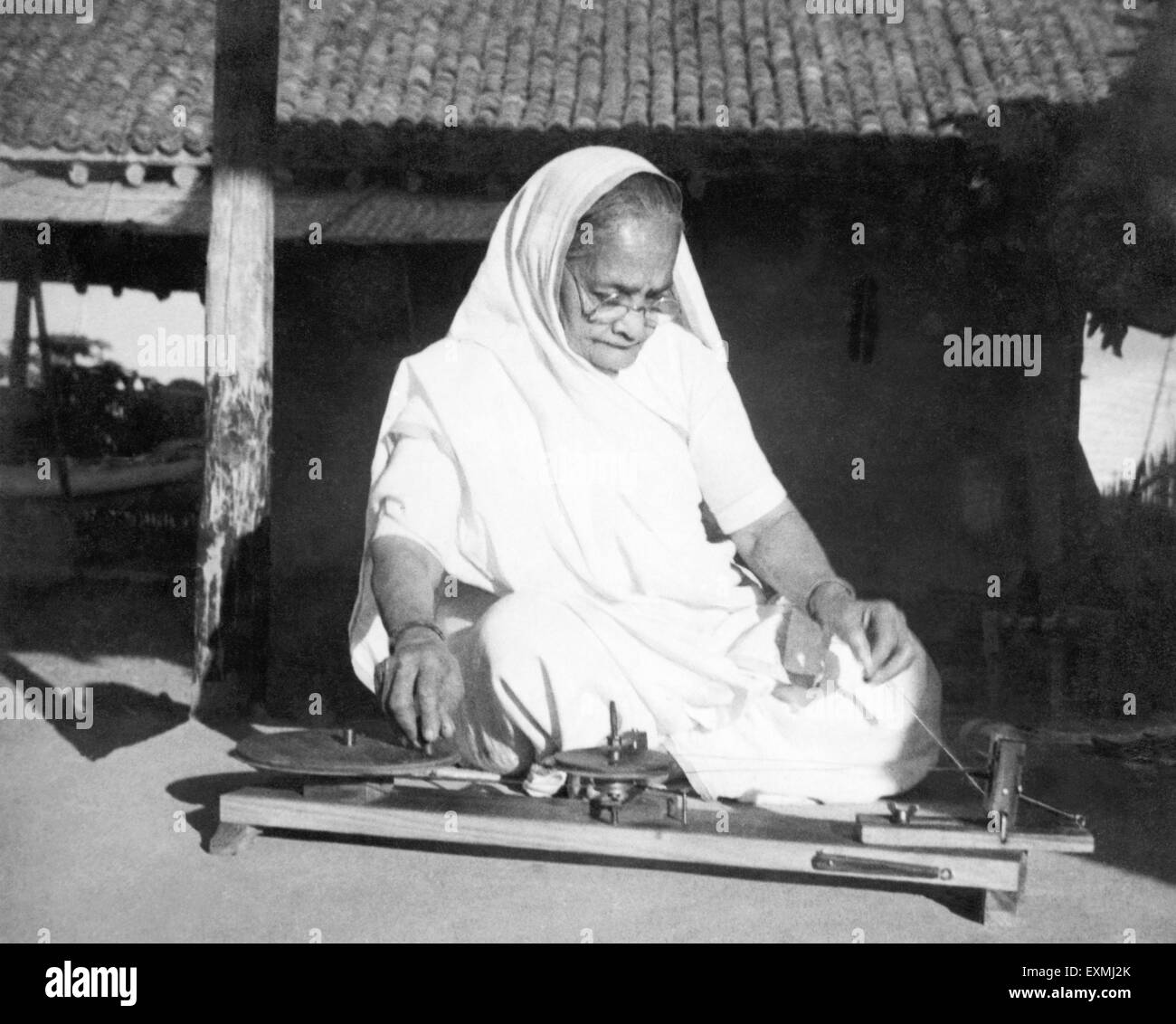

Another textile that is particularly culturally significant to the populace of Rajasthan is the odhni. This is a singular piece of 10 feet long, 5 feet wide cloth draped around a woman’s head to signify different elements of social status. In the Hindu faith, a garment that is stitched is considered to be impure, so this garment is particularly important for women. Interestingly, during the years of British colonization and efforts of Anglicization, the female population of India were the most adamant about sticking to traditional dress, perhaps due to the extreme difference in construction of what was considered to be acceptable clothing. Because of the emphasis put on unstitched clothing, it is easy to see why spinning and weaving would have become such a refined craft in that region. The intense contrast between the native values of garments constructed to last and not need stitches and the factories that now inhabit the area with the literal purpose of creating garments to fall apart is quite poignant.

While fast fashion has most definitely affected the frequency and methods with which traditional clothing is worn in Rajasthan and the rest of India, many Indian designers still turn to khadi as the tried and true way to create garments in India while supporting the working class as well as the country’s culture and customs. Recently, some of the top Indian designers have begun to participate in an event called Rajasthan Heritage Week. This fashion show highlights heritage textiles and fashions while still rolling with the times and encouraging the ever-present growth of modern society in India. Unsurprisingly, khadi continues to be the fabric of choice for the event. As the seasoned designer Hemant Trivedi states, “khadi is a fabric that is redolent of freedom, individuality and of the fact that we are Indians.”