Now that we have established the names and locations of many of the important structures, I will discuss their various functions.

Continue reading Physiology and Function

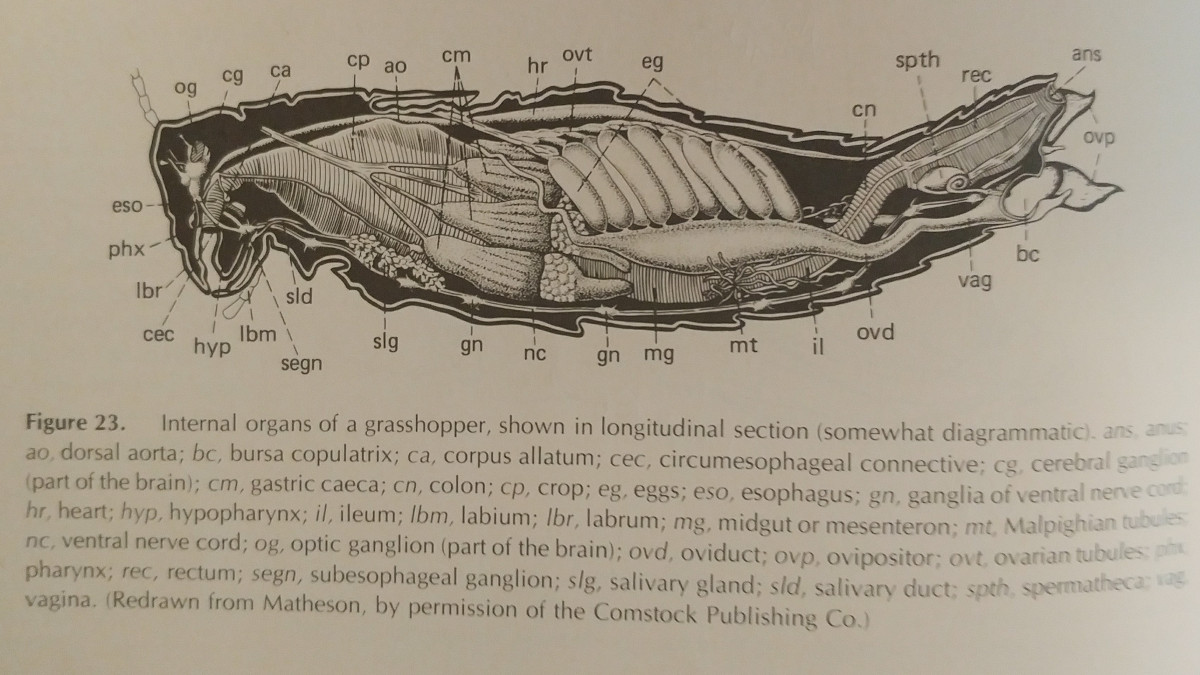

Internal Anatomy of Insects

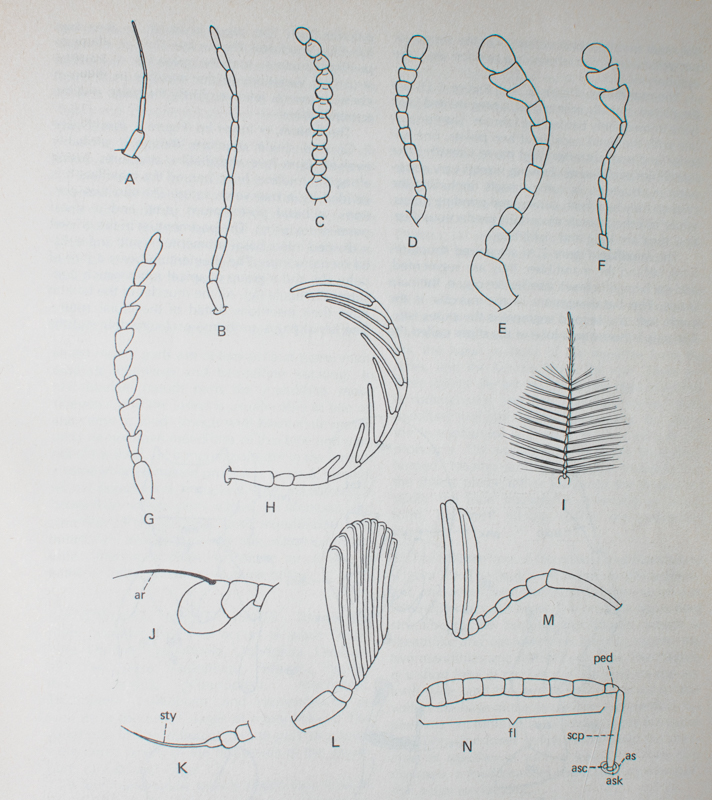

Types of Antennae

Antennae are used to feel, smell, and often hear. They’re also quite variable in appearance, making them an excellent identification tool. The types are listed below with the letter corresponding to the key listed at the end.

Setaceous: Bristlelike, with the segments becoming thinner distally (towards the top). E.g.: Dragonflies. Fig A.

Filiform: Threadlike, with segments uniform in size. Typically cylindrical. E.g.: Ground beetle. Fig B.

Moniliform: Similar to a string of beads, with segments having similar size and typically spherical. E.g.: Wrinkled bark beetle. Fig C.

Serrate: Sawlike. Segments are more are less triangular, especially in the top 1/2 – 1/3. E.g.: Click beetle. Fig G.

Pectinate: Comblike. Most segments posses long, slender lateral processes. E.g.: Fire colored beetle. Fig H.

Clubbed: There are four types of clubbed antennae. The segments increase in diameter distally. Clavate indicates a gradual increase, a such as Fig D or F. Captitate indicates that they suddenly enlarge, such as Fig F. Lamellate posses expanded, laterally forming ovular plate-like lobes, such as Fig M. Finally, flabellate refers to lobes that extend laterally, such as Fig L.

Geniculate: Elbowed, where the first segment is long and the following segments are smaller, and at an angle. E.g.: Stag beetle. Fig N

Plomose: Feathery. Most segments have whorls of long hair attached. E.g.: male mosquitos. Fig I.

Aristate: The final segment is typically enlarged, and has a conspicuous dorsal bristle known as the arista. E.g.: Syrphid fly. Fig J.

Stylate: The last segment has an elongate terminal sty-like or finger-like process, known as the style. E.g. Robber fly. Fig K.

Rudimentary Insect Structure

The most basic segmentation of insects is that of the head, thorax, and abdomen. All insects have these general structures, although they can vary greatly in individual appearance. All of these parts are sclerotized, or hardened, and the body is divided into plate-like areas, called sclerites.

The head is anterior, and capsulelike. It contains the eyes, antennae, brain, and mouth parts.

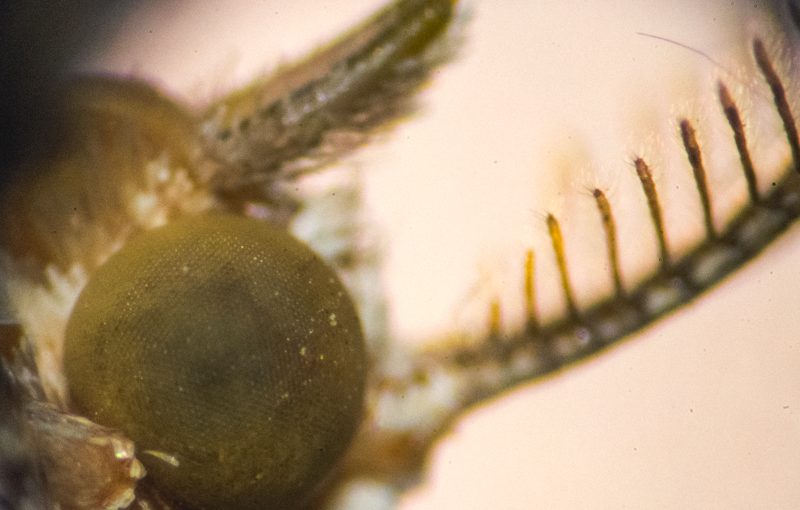

Typically, insects have both simple eyes (ocelli, ocellus plural) and compound eyes. Ocelli are simple photoreceptors, and detect light. Complex eyes are used to create full images of the environment.

The antennae of insects vary greatly, and often are a fantastic tool for identification. Bee mimic flies are one example that can easily be differentiated by their antennae. The Criorhina caudata pictured on the bottom has antennae typical of a fly, while the bumblebee it mimics has longer, segmented antennae. While other structures differ as well, such as the mouth parts and wings, this can be something easily referenced.

Continue reading Rudimentary Insect Structure

Pruning Basics

Apple trees, like most plants, don’t necessarily grow in the way that we want them to. Our apple trees sit on dwarfed root stock, keeping them short, ideally shaped like an upturned bowl. This allows for proper air and light flow, as well as easy harvest.

When pruning in the winter, you can typically remove up to 30% of the biomass. It is best to do heavily pruning during the colder seasons, while the plant is dormant.

There are many indicators of what may need to be removed, and in some cases it may take many seasons to reshape an improperly pruned tree. Basically, you’ll have a few objectives when pruning:

- Shaping the tree for easy harvest

- Removing suckers, which are shoots from the root stock. These are not the same as the tree that is grafted on, and are undesirable.

- Removing water shoots, which are new shoots that reach directly up. These won’t produce fruit in the next season, and are structurally problematic.

- Limiting inter-crossing and growth towards the inside of the tree. Branches that touch eachother can cause chafing, opening up the tree’s flesh for disease and insect pests. Additionally, it reduces airflow and light flow throughout the rest of the tree, making it less efficient.

- Removing any diseased tissues, to limit its spread through the tree or orchard. These limbs should be removed from the orchard after pruning as well.

- Preserve fruiting buds. They appear on older growth, and are stout buds, usually on small stems coming off of the branch.

- Make sure branches have secure angles. Desirable angles usually range from 40-60%, and prevent fruit breakage, and also allow better auxin distribution, leading to more evenly distributed buds on branches.

With these tips in mind, pruning should go fairly smoothly. It is fairly hard to damage the tree beyond repair, and pruning only becomes better informed as you garner more experience while doing it.

It is important to note some of the effects of pruning. Although yield will be decreased, the quality per fruit will be significantly improved. This allows you to sell a more expensive, better quality product, and makes yields more reasonable for small scale farms. Additionally, by limiting the amount of apples the tree can produce, it is more likely it will fruit annually rather than biannually.

The Basics of Rearing Insects

The main objective of insect rearing is to provide high quality insects while maintaining efficiency and affordability.

Continue reading The Basics of Rearing Insects