Historically, the examination of food theoretically and philosophically has been ignored for the most part, Why is that the case? Using Carolyn Korsmeyer’s Gender and Aesthetics as a reference I will briefly explore questions of gendered thinking and potential explanations for the historical dismissal of philosophical explorations of food.

In the world of academia today it is common practice for questions regarding the sensual and the body to be considered trivial compared to questions of the rational mind. Historically, rationality, objectivity and concepts regarding the visual and the mind, have typically been associated with men while the so called subordinate senses of taste, smell, intuition, subjectivity and emotionality have corresponded with women. Food has therefore been regarded as trivial and sometimes even dangerous because of its physical nature that in itself has the possibility of over-indulgence and gluttony. “One reason why taste is disqualified from philosophical approval has to do with the kind of pleasure that it delivers: a very dubious sort, by most accounts, one that leads to self-indulgence in bodily sensation, which if pursued with sufficient zeal, as Christian philosophy warns, eventually leads to th

e deadly sin of gluttony” (Korsmeyer, 89). Philosophers, and thinkers (primarily men historically) have in turn been urged to refrain from pleasures of the body including food, drink and sex, regarding the sensual and physical to be a semi animalistic diversion from higher callings of thinking reflecting nothing more than primitive instincts.

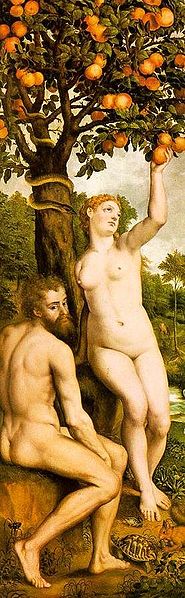

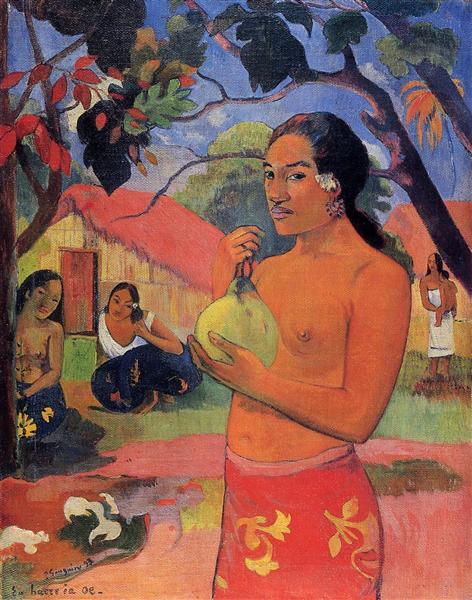

“It is obvious that in most situations and cultures women are the ones who prepare food. What is less obvious- and more interesting- are the gendered ideas associated with body, eating, gustatory pleasure and the sense of taste that function in opposition to the values that cluster around concepts of the aesthetic and the values of fine art”(Korsmeyer, 85). Beyond sex being commonly associated with food in many cultures, it is historically evident in art as well. In Korsmeyer’s Deep Gender chapter she cite’s Paul Gaugin’s portrait of Two Tahitian Women ( a depiction of two women, one topless cradling a platter of fruit just below her chest) and biblical paintings of eve and her apple, among others. She then goes on to state that because of the connections that exist with food and sex, with their clear physical gratification and animal pleasure questions of food and taste are often shunned and almost taboo in their nature.

Though historically most have had no problem acknowledging and accepting the comforting, loving grandmother or mothers place as caretaker in the kitchen, with the women’s standing of authority in the kitchen comes the context that has placed them in this position. “As Kant put it in his early work observations on the feeling of the beautiful and sublime the narrow scope of the beautiful characterizes a woman’s sensibility, whereas a man should strive for the deeper understanding of the sublime. Both are positive capacities, but it is the latter that accomplishes the more profound and commanding scope- aesthetically, epistemically and morally” (Korsmeyer,47). Food-works place becomes one of the beautiful linked to visions of goodness and moral value (without slipping into over-indulgence or teetering into the sensual) the woman’s place becomes one to accommodate and serve as opposed to pushing boundaries and striking intellect characteristics seen as stereotypically masculine.

Though historically women have been considered capable of developing refined palettes and tastes, the model for the ideal arbiter of taste was implicitly male because of the supposed greater mental facility of men and beliefs in their judgments of tastes on complicated subjects to be more sound. “The polarities between feminine and masculine tastes were to serve not only to demote women as taste-setters, but also to criticize and truncate women’s opportunities to participate in the arts” (Korsmeyer, 47). Assumptions of the female experience being less broad and the lack of fostering of women’s talents in all fields historically has led to lack of access, tools, and societal mindset for encouraging the creative endeavors of women. Though more and more women contribute to the arts and academia the historical lack of acknowledgment of the talents, tastes and intellect of women has not subsided. Societal pressures and socialization continue to place women in positions often dismissed as lacking in intellect but with an examination of the practices in art, media, painting and film have perpetuated these ideals continued forward movements in mindsets are foreseeable.