In many of the programs I teach, it is expected that students will keep detailed notes and/or observations of labs and field outings in an organized notebook. This is a two-part undertaking that involves: (1) observation and note-taking in the field (making sure you are dating the pages of your notebook and adding your last name as well) and (2) writing a formal Field Journal entry at the end of each field day.

Journal vs. Notebook

Notebook. The notebook you use for informal note-taking is important, but is generally used only by you. I recommend you use a waterproof field notebook that can easily fit into a large pocket (I like Rite in the Rain All-weather Universal No. 370F-M). Although the notebook is for your own use, it is essential that you make sure to enter your date and location notes on each page along with your last name. After your field time has ended, you should immediately (by the end of the same day) enter and organize your observations in your journal.

Journal. The journal is a clear and formal compilation of the day’s field observations and it written after the field activity ends. Think of it as rewriting jotted down notes for studying. Also think of it as a unique and invaluable archive of observations of the natural world at a very specific time and place: maybe a time and place only you witnessed (or you and a few colleagues). The journal could be read at a later time by another person in order to understand what the environment was like today.

The formal Field Journal itself will be kept in a three-ring binder. The traditional style is a small binder approximate 5.5 x 8 inches with archival-quality paper (acid-free, lignin-free, cotton fiber rag), but you may use a larger binder and a paper of your choice, though you need to make sure you have a means of protecting your journal from the elements. The Field Journal should be organized in chronological order with pages numbered and a table of contents indicating page ranges for each lab/field outing/date.

Each entry in your field journal includes:

OBSERVER/DATE

- Your name (first and last)

- Date (include month, day, year)

LOCATION INFORMATION

- Location description (a specific description good enough to guide someone unfamiliar with our region to your specific place)

- Location map (draw a map from the nearest universally recognizable landmark such as cross streets, a clearly identifiable structure, etc. – again the goal is to guide someone unfamiliar with the area to your place)

- Location coordinates (latitude, longitude in decimal degrees)

HABITAT INFORMATION

- A description of the basic type of habitat/environment you are observing (e.g. forest, coastline) with as much specific information included to provide relevant background to your observations (e.g. the coast line may be a tidal mudflat or it may be rocky and it may be high or low tide – such differences would dramatically influence what you might observe. Likewise, a forest may be dominated by a certain type of tree and may have a specific growth stage such as old growth or early successional.)

CLIMATE INFORMATION

- Temperature (indicate your units)

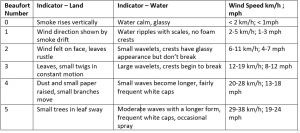

- Wind Condition – Use the Beaufort If wind conditions are stronger than a 4, or if it seems not safe, go out at a later time!

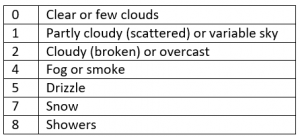

Sky condition – US Weather Bureau codes (yes, there is no # 6)

Sky condition – US Weather Bureau codes (yes, there is no # 6)

- DATA COLLECTED/OBSERVATIONS. The observations you make in a field outing may include a species list of birds, plants, or other biota. It may include data collected for a research project in the form of descriptions, categories, counts, and measurements. It may include descriptive or quantitative characterizations of the environmental from the micro to the macro scale. Anything you observe can be documented.

- For your bird identifications, you will make a list of the bird species you observe including the scientific name, the Genus, Family, and Order. The taxonomic reference you should refer to for this information is the AOS Checklist of North and Middle American Birds http://checklist.aou.org/

- In many cases, you will be collecting data using a specific survey method and then comparing your dataset between or among surveys sites (or looking for relationships in your data). It is important to make sure that your field notebook includes all the information needed to complete your work. If you have an opportunity to work in groups, each group member should keep a complete record of the activity. This ensures that field data are never truly lost because each group member has a complete record of all important data.

- Additional observations. Anything you note or observe individually. Making individual observations helps to ensure that the group doesn’t collectively miss any important information.

ILLUSTRATIONS

- Illustrations are important components of a good field notebook. They do not need to look great, but can help you describe your observations in an alternative format to writing.

NARRATIVE OF THE EXPERIENCE

- The narrative captures the essence what happened (e.g. folks in your group, your goals for the work, what you did, hiccups encountered along the way, and any additional observations you made while working, new questions that occurred, etc.).