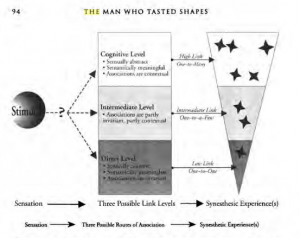

This week I explored the neural interconnectivity of shared general-domain functions of the brain and how it can be used to enhance an experience with food. At first I was unable to find cited articles on music and food, so I explored the research on language and food. The following quote comes from an article providing evidence for shared general-domain functions of the brain and the usefulness of neural connections in application.

“If long-term experience with music only sharpened shared acoustic processing abilities in language, then this would indicate that a domain-general processing mechanism account would suffice. However, in order for a theoretical account to be complete, transfer effects should be taken into consideration. If long-term experience in one domain not only sharpens common characteristics but also domain-specific characteristics, this would indicate that experience can transfer from one domain to the other.” (Asaridou & McQueen 2013)

The knowledge that experience can transfer from one domain to another does not mean that it can be applied, as described by the following quote:

“They [Bidelman et al. 2011b] found that tone language experience enhances subcortical pitch processing in a manner similar to musical experience. However, this was not evident at a behavioral level. Although Mandarin speakers performed better than non-musicians, the FFR (Frequency Following Response) response accuracy was a successful predictor of behavioral performance only for the musician group. Thus, while subcortical pitch encoding is sharpened in tone language speakers, this is a necessary but not sufficient condition for perceptual advantages to occur in behavior.”

Tonal language speakers have an increased behavioral advantage to differentiate between tones, timbre, and texture in conversation with more than one person while the musician group’s Frequency Following Response was more accurate as a predictor of behavioral performance (potentially due to varying subject content across all communication through spoken language).

The limitations of the neuroplastic development amongst musicians relative to Japanese and Dutch speakers in the context of differentiating between language lead to concluding thoughts as described in the following list of quotes.

“In a cross-linguistic experiment with Japanese and Dutch speakers, Sadakata and Sekiyama (2011) showed that although discrimination and identification of non-native temporal and spectral speech contrasts was better in musicians, there were stimuli for which musicianship had no advantageous effect.”

“It is therefore not automatically assumed that a domain-general sound processing device is more resourceful, and this can only be manifested when new learning is required.”

“The fact that musicians are better in segmental processing of a non-native language is an example of transfer as defined in this framework.”

Interestingly enough the neural connections made by differentiating between tone, timbre, and texture do in fact overlap if the two functions are reinforced by the principle that underpins both behavioral functions that activate a shared general-domain.

In examining studies on tone-deaf, tone-based language speakers, the authors stated: “Interestingly, neuroplasticity in pitch processing at this subcortical level of sound encoding is not restricted to the domain in which pitch contours are relevant. Strong effects of context which arise in other studies do not seem to influence brainstem responses. This finding led Krishnan et al. to conclude that language and music are “epiphenomenal” with respect to subcortical pitch encoding and that the encoding mechanism has evolved to capture information in the acoustic signal that is of relevant in each domain, in order to facilitate higher-order cortical processing of pitch across domains.” (Arasidou & McQueen 2013)

The language in the last sentence of this quote interests me because the capturing of acoustic signal that is relevant to each domain in order to facilitate higher-order cortical processing of pitch across all domains, which includes eating because as I learned pitch is interconnected with the perception of smell, further reinforcing the vibration theory of olfaction rather than the shape theory of olfaction.

The following article I found summarizes the literature on the multisensory perception of flavor and cited other research to show that flavor is not defined as a separate sensory modality but as a perceptual modality that is unified by the act of eating.

“… according to the amodal approach, perceptions are not based on sensations but rather result from a process of information extraction. The information is abstract and does not depend on the particular sensory modality in which it was generated. Properties of objects can thus be ‘interpreted’ by different sensory channels. As a consequence, sensations are specific to each sensory modality, but perceptions are not (e.g., Gibson, 1966, 1979; O’Regan & Noe, 2001; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1991)” (Auvrey & Spence 1025)

The authors referenced the use of ecological theories of perception to define flavor as a perceptual modality which was incredibly exciting to hear because it should support the vibration theory of olfaction. After reading Shepherd’s Neurogastronomy I learned that the olfactory system is used in part to detect danger, pheromones, and food. After discovering concentric circles last week it was brilliant to hear that the ecological theory of perception supports the potential for an increased understanding of the interconnectivity of smell and hearing. The following quote lead to an increased understanding of the potential connection between the otolith organ and this articles understanding of olfaction constituting a dual modality.

“Olfaction thus appears to constitute a ‘dual modality’ in that it explores objects both in the external world and within the body.” (Auvrey & Spence 1022)

The parts of the otolith organ helps coordinate gravity, balance, movement, and directional indicators which interests me because of the interaction between this organ’s proprioceptors and the vestibular system in the brain creating exteroception, a perception of the outside world, versus interoception, how one perceives pain, hunger, or another emotion. The similarities between how the ear operates and the apparent constitution of dual modality by olfaction is reinforced by the following quote.

“In addition, the fact that the same unfamiliar odor can induce different taste qualities (i.e., sweet or sour) as a function of its repeated pairing with a specific tastant shows that the modification of taste qualities by odors is not due to a particular feature of the odor but is a consequence of learning instead (Stevenson & Tomiczek, 2007).” (Auvrey & Spence 1018)

Going back to a previously listed quote on the article on evidence for shared general-domain functions:

“The fact that musicians are better in segmental processing of a non-native language is an example of transfer as defined in this framework.”

Varying taste qualities depend on behavioral experience and learning that result in matching an unfamiliar odor to, in this example, sweet or sour. As mentioned in the quote listed before the quote on musicians, the repeated pairing with a specific tastant shows the modification of taste qualities as a consequence of learning. Musicians are commonly used in studies of neuroplasticity in the human brain, and when examining the malleability of the interpretation of a sour taste and sweet test, it tends to make more sense to think about minor and major chords (sour and sweet) given the key (tastants) of the song (chemical releases of the food itself) and the style in which it is played, or how it is perceived (previous flavor experiences).

The following quote describes the interdisciplinary neurological connections that go into the flavor of a meal.

“The multiplicity of interactions between taste, smell, touch, and the trigeminal system (not to mention hearing and vision) has led numerous researchers to propose flavor as the term for the combinations of these systems, unified by the act of eating (e.g., Abdi, 200; McBurney, 1986, Prescott, 1999; Small & Prescott, 2005).” (Auvrey & Spence 1026)

The unification of taste, smell, touch, and the trigeminal system has lead me to focusing on the unmentionable hearing and visual side of flavor. As mentioned in the first quote listed from this article, “perceptions are not based on sensations but rather result from a process of information extraction”. This quote reminded me of the difference between retronasal smell, smelling from the mouth to the nose when eating, and orthonasal smell which is smelling something that exists in the world. The following quote further supports the theory of shared general-domain function.

“Thus, smelling and tasting need not be defined by receptors and nerves; they can instead be defined by their functions in use. As a consequence, the same olfactory receptors can be incorporated into two different perceptual systems, one for sniffing and the other for eating. Smelling would be restrained to its main function, that is, the detection of stimuli at a distance by means of their odors.” (Auvrey & Spence 1022)

The quotes mention of “the detection of stimuli at a distance by means of their odors” reinforces my initial belief of the connection between the vibration theory of olfaction and hearing frequencies. The two different perceptual systems of smell in addition to olfaction detection of danger, pheromones, and food and the connectivity between the brain’s vestibular system leads me to believe that the use of concentric circles was developed through nomadic campfire encounters in which language barriers were crossed, danger was heightened either from human to human interaction or a fear of a new environment, a high likelihood of increased pheromone release, and of course, food.